UI pediatric experts save toddler’s life after cardiac arrest

For 45 minutes, Quinn Anderson’s care team at University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital tried to restart his heart. Doctors placed the 3-year-old boy on an advanced form of life support called ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), which does the work of the heart and lungs when they aren’t strong enough.

It had already been a long journey for Quinn, who was diagnosed with four congenital heart defects in his first week of life. Now, he had no heart function, and his organs were failing.

Quinn’s parents, Sara and Dennis Anderson of Chariton, Iowa, received a daunting suggestion: “We were told to call our families to come say goodbye.”

Three days after Quinn’s heart stopped, the Andersons asked that one more echocardiogram be taken to confirm that their son’s heart was too weak to recover. The ultrasound test showed that Quinn’s heart was showing some improvement.

“This showed us that Quinn wanted to fight, so we let him,” Sara says.

Quinn’s journey

Before he was born, Quinn was diagnosed with DiGeorge syndrome, a chromosomal disorder caused when part of chromosome 22 is missing, which often causes heart defects and other conditions. He was diagnosed with a severe form of tetralogy of Fallot, a rare birth defect that affects blood flow through the heart, when he was born in October 2018.

Quinn was just 2 days old when a Des Moines doctor referred him to UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital. In those first few days of Quinn’s life, pediatric cardiologist Osamah Aldoss, MBSS, MD, performed a procedure using a catheter to create better blood flow in the newborn’s heart. Two open-heart surgeries and several other procedures followed.

During Quinn’s first open-heart surgery in September 2019, he developed a respiratory virus and was readmitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). He remained hospitalized for a month, and his cardiology team inserted a pacemaker to help his heart beat normally.

The following summer, the lead on Quinn’s pacemaker malfunctioned.

Aldoss and cardiothoracic surgeon Marco Ricci, MD, MBA, soon determined that Quinn had grown too much for the tube that connected his heart to his lungs. He would need another surgery.

“Everybody always goes above and beyond to make sure that we, as the parents, are well-informed on what’s going on with Quinn while providing the best care for him. Our care at the university has been fantastic.”

On Nov. 11, 2020, Quinn had his second open-heart surgery. Nine days later, he started running a fever. A second surgery led to the discovery of a fungal infection developing in his chest and around his pacemaker.

Quinn had his pacemaker removed and a temporary device taped to the outside of his body with a lead that went through his right internal jugular vein. The procedure had never been performed on a pediatric patient in Iowa who was as small as Quinn, according to Ian Law, MD, director of pediatric cardiology at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital.

Quinn’s chest was open for 10 days of his 74-day stay in the hospital. He had several washout procedures to keep the wound area clean and free from infection. Quinn remained intubated for 47 days, and received a new pacemaker before he was discharged.

Almost a year later, in January 2022, Quinn had an asthma attack and was hospitalized near his hometown. Sara wanted Quinn to be at a hospital that knew him and understood his condition, so she asked for a transfer to UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital.

Quinn went into cardiac arrest a day after arriving in Iowa City.

Although he was able to be removed from ECMO a week after going into cardiac arrest, his liver and kidneys were injured, and he developed acute respiratory distress syndrome. His care team told Quinn’s parents that he might not be able to overcome his sick lungs, and his only option to survive was to go back on ECMO.

“We asked lots of questions and tried to stay as positive as we could, but when you’re told that your baby’s probably not coming home, it’s hard to cope with,” Sara says.

Within a few days, Quinn’s lungs were showing improvement, and his liver healed with little intervention. Quinn started dialysis while his kidneys healed.

After one-and-a-half months, Quinn was able to come off dialysis permanently. He hasn’t had any long-term hospitalizations since that time.

Expert care you can trust

Throughout Quinn’s journey, Sara has advocated for him to receive care at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital. She says having all of Quinn’s specialists in one place has been helpful for their family.

Quinn sees experts in ophthalmology, cardiology, nephrology, genetics, gastroenterology, and critical care medicine. He also sees specialists at the Center for Disabilities and Development.

Sara says the Child Life program uses distraction methods to ease some of the trauma Quinn associates with hospital visits. She says the specialists working with Quinn have become familiar faces for the Anderson family, allowing them to develop relationships to make visits more comfortable.

“Everybody always goes above and beyond to make sure that we, as the parents, are well-informed on what’s going on with Quinn while providing the best care for him,” Sara says. “Our care at the university has been fantastic.”

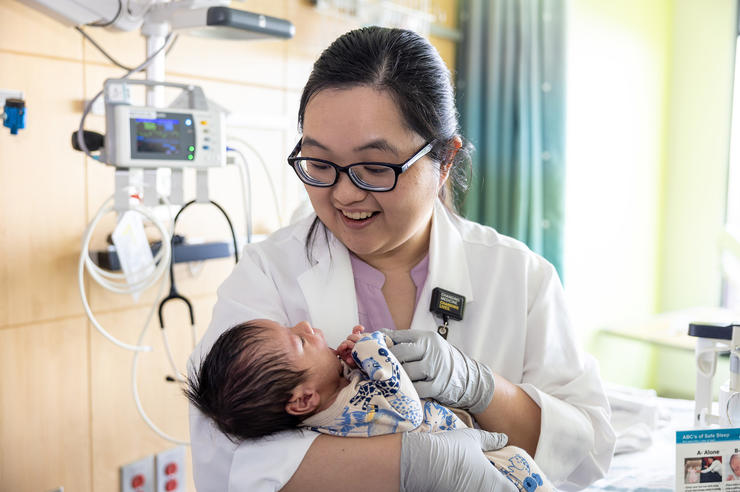

Heart problems can affect young children, adolescents, or the baby in the womb. If there are concerns about your child’s heart health, your pediatrician may recommend a cardiologist, a specialist in the detection and treatment of heart disease in children. The pediatric cardiologists at University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital are dedicated to providing compassionate, state-of-the-art and convenient delivery of care to children and young adults.

The pediatric cardiology division offers complete clinical services for the diagnosis and treatment of congenital and acquired heart disease in babies, children and young adults.

Moving forward

Today, Quinn has some long-lasting effects from his cardiac arrest. Sara tube-feeds him three times a day, and Quinn has weekly sessions involving occupational therapy and hippotherapy (which utilizes the natural gait and movement of a horse to provide motor and sensory input).

“With all the different services we receive from the university he is able to live a happy, healthy-for-him life,” Sara says.

When Quinn’s family makes the five-hour round trip for his appointments, they work with continuity of care teams to schedule all the appointments on the same day. Quinn will have at least one or two more open-heart surgeries to repair his defect, and several more trips to the catheterization lab.

Now 5 years old, Quinn enjoys playing with his toys, going to preschool, cuddling with his dogs, and spending time with his older sisters and brother.

“He’s really just an amazing kid that has overcome some tough obstacles,” Sara says.

Sara offers this advice to parents: “Listen to your gut when it comes to advocating for your child’s care.” She knows following her instincts and pushing for care at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital helped Quinn get to where he is today.

“We are eternally grateful for each and every one of the PICU staff and specialty teams Quinn sees,” Sara says. “Without them, their dedication and their faith in Quinn, we wouldn’t have our baby home with us.”