UI cardiologists save Iowa grandmother’s heart

In 2022, Maria Andrade noticed she was having difficulty catching her breath while out on her daily walks.

“I could feel the palpitations in my heart; it would change the way I would breathe,” says Andrade, of Kalona, Iowa. “It was happening more and more frequently when I was walking, but also when I was working around the house.”

Andrade was evaluated by Osamah Aldoss, MD, a pediatric cardiologist and medical director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory, at the Adult Congenital Heart Disease clinic in September 2022. He determined Andrade had sinus venosus atrial septal defect (SVASD), a rare defect of the heart that, over time, caused increased blood to the right side of her heart and flooded the lungs.

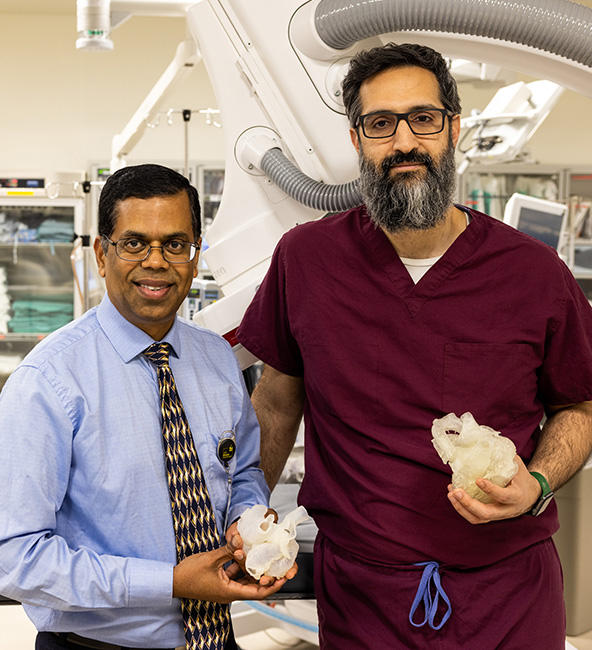

University of Iowa cardiologists Ravi Ashwath, MD (left), and Osamah Aldoss, MD

Though the condition is a congenital heart defect—it was present at birth—Andrade wasn’t fully affected by it until late 2022.

“With this condition, there is a hole between the two receiving chambers of the heart along with abnormal connection of a pulmonary vein and until recently it almost always needed a surgical repair to correct it,” says Ravi Ashwath, MD, a pediatric cardiologist and medical director of imaging at the hospital. “Not only is there the hole that requires surgery, but there is also an abnormal vein that comes back from the lung that needs to be routed to the correct chamber. It makes this a complicated procedure, so open-heart surgery has always been preferred.”

Because of her underlying health history—coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer—surgery was a very risky option. The team started exploring other methods to correct her defect in a less invasive way.

Instead of open-heart surgery, the Iowa team would repair Andrade’s SVASD using a transcatheter procedure in the catheterization lab, correcting the defect by going through blood vessels. Aldoss says this method required a lot of collaboration and planning—this procedure marked the first time it would be performed in Iowa, and very few health care teams across the country have experience with the method.

Dr. Aldoss and his catheterization team performed bench testing on a 3-D model of Maria’s heart to evaluate the procedure, making sure it was doable.

Intercontinental collaboration

In November 2022, Ashwath and Aldoss reached out to the congenital cardiology team in the United Kingdom who had experience with this type of procedure, collaborating on the imaging and gaining a better understanding of where the procedure would take them.

The teams—one at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital and the other in the United Kingdom—worked together through virtual reality technology and with the use of a 3-D heart to determine how best to approach the transcatheter procedure.

Ashwath, director of non-invasive imaging and cardiac MRI, did advanced imaging to more closely define where the hole was located and the relationship of the abnormal vein. The imaging helped the team create a 3-D model of Maria’s heart to help them better visualize the defect in physical form.

Aldoss and his catheterization team performed bench testing on the 3-D model to evaluate the procedure, making sure it was doable.

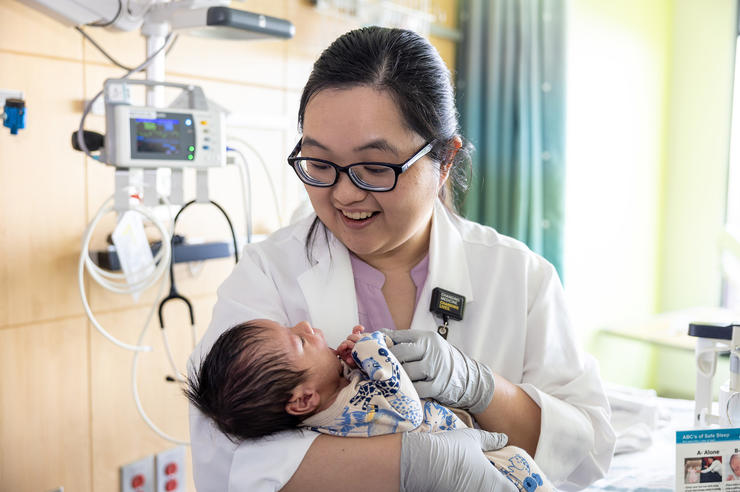

After the procedure, Maria Andrade has been able to care for her grandchildren. “I’m so glad I was able to continue taking care of the babies,” she says.

Andrade’s procedure was done on Dec. 21, 2022, and she was able to go home the next day.

“When she first came to us, she clearly had heart failure symptoms from this defect,” says Aldoss. “Now the heart doesn’t have to work nearly as hard, and she’s feeling much better.”

In addition to a longer hospital stay, open-heart surgery with comorbidities would have come with some restrictions for recovery, such as no heavy lifting for six weeks. For Andrade, that would have been devastating.

“We had one grandson that I was taking care of, and another on the way,” she says. “I’m so glad I was able to continue taking care of the babies.”

Now, she says, she’s back walking every day, taking care of her grandsons, and freely moving around her home without running out of breath.

“It’s incredible they were able to make me feel so much better without the surgery,” she says. “I’m very grateful for such a wonderful team.”

Andrade is also grateful for another part of her care team: the hospital’s interpreting team. Maria’s primary language is Spanish, so she relied on hospital interpreters to communicate with her surgical team.

“Everyone has been so wonderful here,” she says.