Afro House: Empowering, supportive, inclusive

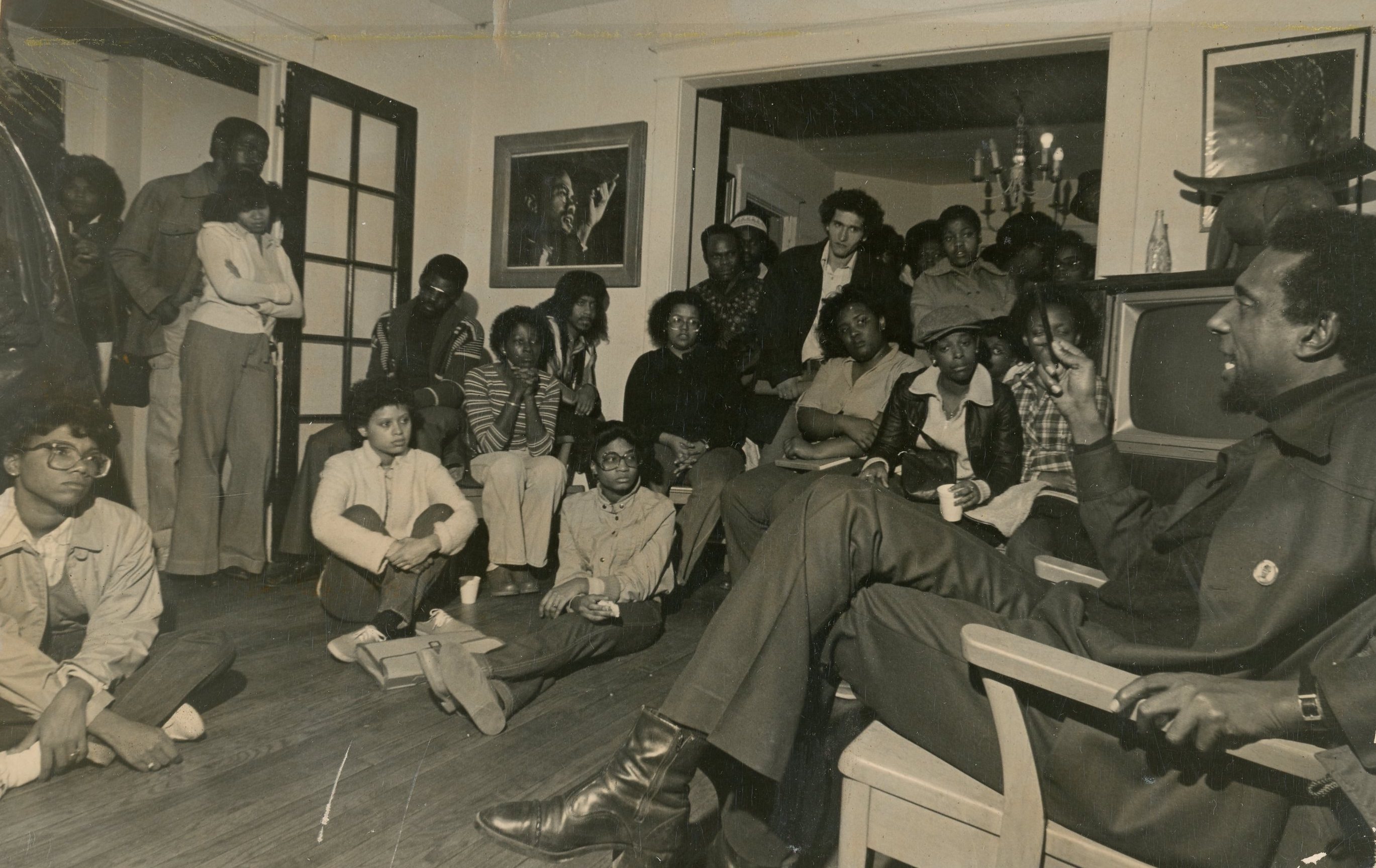

In announcing the recent opening of a newly established University of Iowa Afro-American Cultural Center, a November 1968 story in the Daily Iowan noted that the center might not exist beyond the spring semester.

“It was basically a beta test,” says Jamal Nelson, coordinator at the now-named African American Cultural Center, more commonly known as the Afro House. “They wanted to see if students would use it and see it as a resource, and then find a space where it could be more permanent.”

Fifty years and three locations later, the Afro House continues to prove a valuable resource for black students on the UI campus. It’s a community gathering space that—much like it did in 1968—gives students a place to eat Sunday dinner with friends, study, play games, watch movies, sing, dance, hold panel discussions and cultural events, and just hang out.

“The physical space is reflective of blackness, and I think you would be hard pressed to find other spaces on campus that reflect that type of racial identity,” says Tabitha Wiggins, assistant director for multicultural programs. “Students can see themselves reflected in those spaces, and that’s really powerful. It does a lot for their sense of belonging.”

The Afro House was born in the late 1960s out of black students’ desire for a place to call their own on a predominantly white campus.

Top photo: Reanna Lewis, left, who sometimes goes by Lochemet Perach, chats and raps with Z.o.n.e. (Zones.Only.Neglect.Elevation) during a cypher at the African American Cultural Center. A cypher is an event where the “floor is opened to anyone who wishes to rap and flow.”

“It was created as a result of student activism related to the civil rights movement and was on the wave with other black cultural centers that were founded around the country,” Wiggins says. “It also paved the way for the other three cultural and resource centers on campus to be created.”

The first of those centers, the Latino Native American Cultural Center, formed just three years after the African American Cultural Center, in 1971. Several decades later, the Asian Pacific American Cultural Center (2003) and the Pride Alliance Center (2006) were established.

Melissa Shivers, interim chief diversity officer and vice president for student life, says it’s important to understand the history of the Afro House and to recognize its continuing influence on students’ lives.

“A lot of the campus community wouldn’t necessarily think we’d have such a large investment in cultural and resource centers at Iowa,” Shivers says. “They are a bit of a hidden gem for a lot of people. But we can’t hide them. We need to tell their stories. They are so impactful for people in lots of different ways.”

As the Afro House celebrates 50 years of service to black students and the wider community, UI leaders and students recognize that many of the issues that prompted its creation still exist. African American student enrollment at the university stood at 3 percent in fall 2018, only slightly higher than the estimated 1 percent in 1968. And while racial tensions that gripped the country in 1968 may not be exactly the same as today, they still remain.

“We’re in a post-Obama period where I think we thought that things were getting better, but we find that elements of racism are still out there,” says Venise Berry, UI associate professor of journalism and African American studies. “When you’re battling that and trying to go to school, you need a space where you can actually feel comfortable and safe. A place where you can come and be with folks who understand you and support you.”

“While we’re committed to preserving our history, we’re also looking for innovative ways to help students today,” Wiggins says. “We’ll continue to provide resources and find new resources. We’ll do what we have to do to persist and help students be successful and graduate.”

Students lead charge to establish Afro House

The UI was one of the first academic institutions to open admission to African Americans, but these students often had to overcome barriers that white students did not. Black students were first allowed to live in the residence halls in 1945, but the challenges didn’t end there—housing or otherwise.

“(Black) students and staff members still feel discriminated against in their attempts to find housing, but they are not inclined to go through all of the trouble of working through the complicated human relations procedures to bring charges,” read the minutes from a May 8, 1967, meeting of the UI Committee on Human Rights. “… Students still complain that some professors on the campus are discriminating. Again, they foresee only difficulty for themselves in pressing charges.”

“While we’re committed to preserving our history, we’re also looking for innovative ways to help students today. We’ll continue to provide resources and find new resources. We’ll do what we have to do to persist and help students be successful and graduate.”

As UI administrators discussed how to increase minority enrollment, Charles Derden, president of the Afro-American Student Association, led the charge for a black cultural center. Students eventually found an ally in the Committee on Human Rights, particularly in member Philip G. Hubbard, dean of academic affairs who later became the first African American vice president at a Big Ten university.

In a 1968 report describing the need for a black cultural center to UI President Howard Bowen, the committee said “a central gathering place would provide a social gathering spot as well as a place for academic and personal assistance. The feeling of togetherness created by such a center will help overcome the otherwise foreign element of the unfamiliar environment.”

The Afro-American Cultural Center celebrated its opening in a house at 3 E. Market St. during the 1968 homecoming week. Hubbard told the Daily Iowan at the time that the center would serve as a “platform from which black students can express themselves through literature, art, music, plays, poetry, and lectures.”

Hubbard also stressed that the center was a service to the entire community, not just black students.

“In many places, there is a general ignorance about Afro-American culture in general,” Hubbard said. “The center is an opportunity to educate the entire community.”

Even as black students settled into the new Afro House, they knew the location—and perhaps the center itself—was only temporary, as the university had plans to raze the half block where the building was located for a parking lot.

The center proved popular, however, and Hubbard touted its success to the Board of Regents, State of Iowa, on April 9, 1970.

“The survival in the classroom of a number of University of Iowa black students can be attributed to the presence on campus of an Afro-American Cultural Center,” Hubbard said, adding that the center provided black students with a “special environment where they can relate to others who share a common culture in the midst of a community which is receptive and generally friendly but nonetheless alien.”

Hubbard also mentioned that the UI center had served as a model for other universities that wanted to open similar centers.

Having passed its test, the Afro House moved to 26 Byington Road in 1971, then to 303 Melrose Ave. in 1976, the location it still calls home.

This space provides a supportive and inclusive environment, and programs that empower students, faculty, staff, and community members to excel in their endeavors, stretch themselves to experience diversity, engage in activism, make positive choices, and serve their communities. (Logo designed by UI art student Essex Hubbard in the 1970s.)

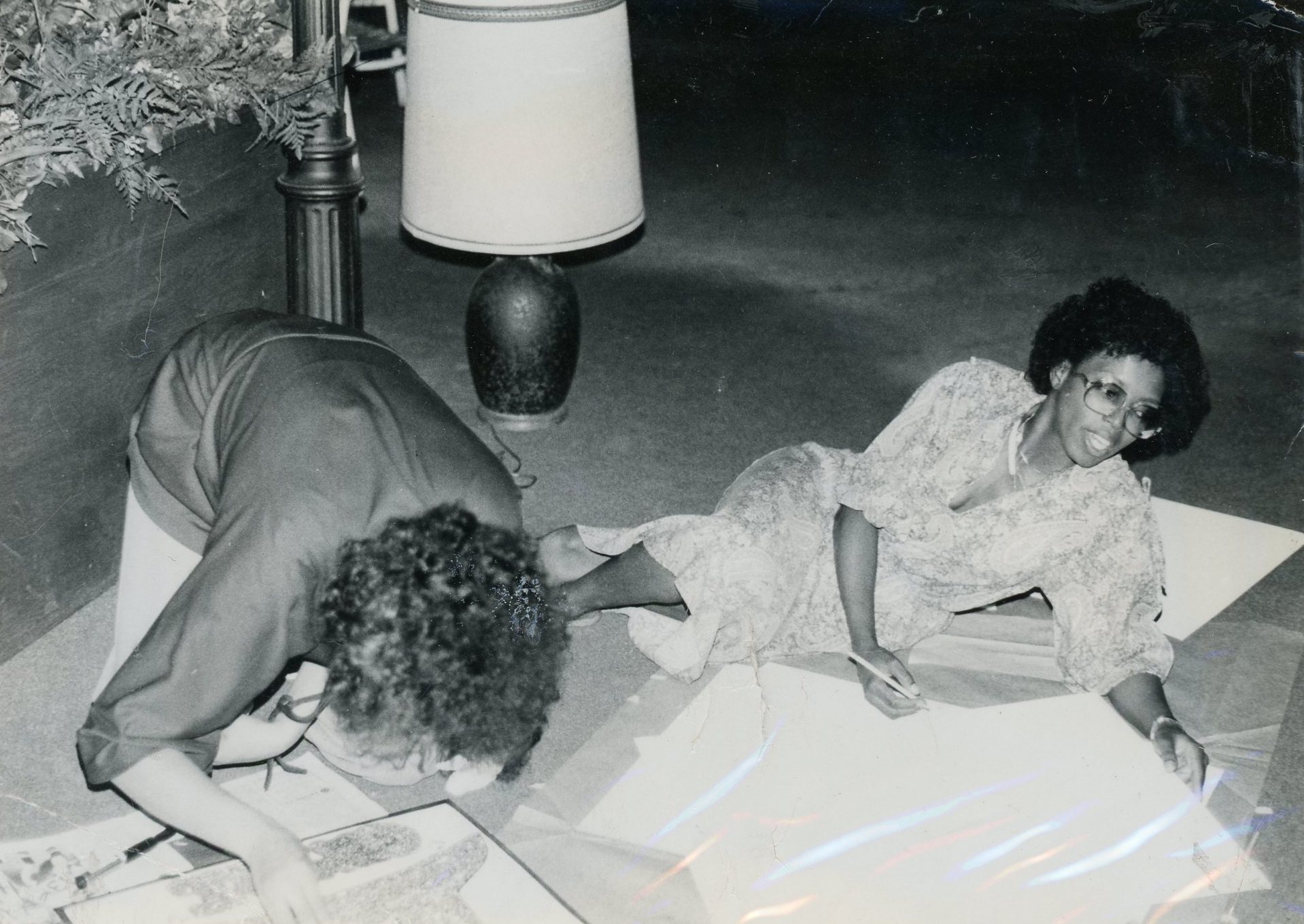

“We were doing the black power and unity thing in the ’70s, so the Afro House was a really important place for African American students on campus, and we spent a lot of time there,” Berry says. “We went there to study. We went there to hang out. I remember picnics, throwing meat on the grill. We played various card games like Bid Whist and War. It was definitely a community spot.

“And oh, we had some wonderful parties,” Berry adds. “I remember we’d dance so much that the floor would bounce and we’d come out sweating. That’s how much fun we would have.”

Berry also served as assistant manager of the Afro House and helped with programming. One community event she helped plan along with her sorority, Delta Sigma Theta, was a children’s workshop one Saturday afternoon a month for African American children from the community. There, they would play games, take field trips, and host various events.

Sabra Mitchell, a third-year student from Iowa City working toward a major in marketing and accounting and a minor in art, says the Afro House is still a community spot. She first became acquainted with the Afro House through the monthly Sunday dinners and says among her favorite memories is watching her fellow students play boisterous games at the house.

“It gets crazy and loud and everyone has fun,” Mitchell says.

Mitchell says the Afro House, along with the other cultural and resource centers, provide an opportunity for community bonding.

“It’s important for people who identify with the African American, Latino, LGBTQ, or Asian-Pacific community to have places they can go and find people who are like them,” Mitchell says. “The cultural centers are places where people can feel safe when they may not feel safe in other places on campus. For people who may feel like they’re alone, it’s nice to know you can go to these cultural houses and find friends outside of the classes you take. Each cultural house is a safe space and a home away from home.”

While some things change, others remain the same

The Afro House has seen a lot of history in its 50 years, and like the rest of the world, some things about it have changed while others look very similar.

“The role has changed somewhat,” Wiggins says. “It was clearly started through activism and was highly political. Now, I think the role of the student organizations that are affiliated with Afro House, other than maybe the NAACP, are highly social organizations and are not as politically active as they once were. I think that’s the biggest shift.”

At 50, the African American Cultural Center is not only the oldest of the UI’s cultural centers, but also builds on a legacy of community that stretches back to the early 1900s.

1914: Iowa’s first traditionally black fraternity, Kappa Alpha Psi, was established.

1945: Betty Jean Arnett moves into Currier Hall, becoming the first black student to live in a residence hall. Although the UI began admitting black students in the 1870s, its residence halls excluded African American students until this year. Prior to this time, black students stayed in boarding houses run by local African Americans such as Junious “Bud” and Elizabeth “Bettye” Crawford Tate, Chester and Estelle Ferguson, Allen and Helen Renfrow Lemme, and the Iowa Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs.

1966: Philip G. Hubbard, who received a PhD from Iowa in 1954, becomes the first African American vice president at any Big Ten university when he is promoted to vice president for student services and dean of academic affairs at Iowa.

1967: Charles Derden, president of the Afro-American Student Association, leads the charge for a black cultural center.

1968: In the spring of this year, the UI Committee on Human Rights, with Hubbard as a member, recommends to UI President Howard Bowen that the university establish a black cultural center.

1968: The Afro House opens during the fall semester on 3 E. Market St., retaining the “home away from home” environment first fostered by the boarding houses. Established with support from the Afro-American Student Association, UI administration, Faculty Senate, Committee on Human Rights, and the UI Student Senate.

1971: The Afro House moves to 26 Byington Road.

1976: The Afro House relocates to its current address at 303 Melrose Ave.

1998: UI administrators begin discussing a plan to close individual cultural centers and create one multicultural center in the Iowa Memorial Union. Students spend the next years opposing the move, a battle they would win.

2016: The UI renovates its cultural centers and adds a Cambus stop. Improvements at the Afro House include new furniture, oven, microwave, and commercial-grade picnic table, as well as removing walls to create a large space for group activities.

2017: A boost in funding to the UI’s four cultural and resource centers results in hiring more student employees and full-time coordinators.

2018: The Afro House marks its golden anniversary with a Homecoming reunion.

Nelson agrees and notes that a key role of the Afro House remains the same.

“It was created because there was a lack of presence; we needed something,” Nelson says. “We may not be as politically charged as we once were, but we were and remain a resource. What I hope students do, what I push students to do, is use it as a hub, or a space where everyone knows they can come to this spot. And I see students do that.”

In his 1970 report about the Afro House to the regents, Hubbard said an assumption that such centers tend to insulate minority students from the general educational community was inaccurate and unfair. He said the Afro House was not unlike other university-sponsored organizations that existed because of the needs and interests of a particular set of students.

Shivers says this assumption can still be found today, and it is just as untrue as it was in 1970.

“It’s not to suggest that African American students don’t want to live in a world that is different from them. They do that every single day,” Shivers says. “But much like any student organization, they come together because they have like interests. People choose to be a part of a group because of their interests or because of what it stands for or represents, and we don’t ever say they are self-segregating. But sometimes when it comes to racial and ethnic identity groups, it can be perceived very differently. It’s important to recognize that their significance and relevance is just the same as other groups that we have on our campus.”

One aspect of the center that has evolved over the years is its relationship with the administration. A live-in manager was named when the Afro House opened in 1968, and a seven-member advisory board of two faculty members and five students was elected by the Afro-American Students Association. This setup has changed several times over the years.

“The institution has had an interesting relationship with the center,” Wiggins says. “Philip Hubbard was a big supporter, but over the years the administration kind of took that support back and told students to raise it up and make it have the profile it has. They would have to be the proponents for programming in that space. In more recent years, Tom Rocklin and Melissa Shivers went back to the idea that we need more institutional support for the cultural resource centers.”

A boost in funding in 2017 resulted in hiring full-time coordinators for the cultural and resource centers, including Wiggins and Nelson. While the coordinators oversee programming, Nelson says it’s still largely student driven. He says he’s there to provide resources to bring the students’ visions to reality.

“It’s not taking any roles or work away from students; it’s just empowering that work,” Nelson says. “When it comes to finding funding or resources on campus, they need someone on the administrative side. They all know they can come to me if they need help. They know they have a university connection. I think that connection had been missing before, but this shows we’re back to creating that institutional support.”

“We’re in a post-Obama period where I think we thought that things were getting better, but we find that elements of racism are still out there. When you’re battling that and trying to go to school, you need a space where you can actually feel comfortable and safe. A place where you can come and be with folks who understand you and support you.”

Wiggins says she thinks of the Afro House as the hub of a bike, with the spokes representing factors such as academic success, racial identity development, leadership development, and financial aid help.

“The coordinators have to be generalists in their role to support students,” Wiggins says. “Sometimes they have to wear a hat as a counselor. Sometimes the hat of a program planner. And sometimes the hat of a financial aid counselor.”

She says the extra support for students already is making a difference.

“Students are able to say we have a full-time person dedicated to leadership development, dedicated to the facility’s management, dedicated to creating programming during Black History Month as well as other programming through the year,” Wiggins says. “To have that dedicated person in the center for 40 hours a week has made tremendous leaps and bounds for the students’ sense of belonging.”

Shivers says she’s heard firsthand about the impact coordinators have made on students’ lives.

“At the 50th anniversary celebration, it was fascinating to hear the students talk specifically about the staff who work in Afro House as their rock and a person they can connect with,” Shivers says. “A number of our students come here looking for individuals who can serve in a mentor capacity, and we are building that into these spaces. That’s pretty special.”

The building itself also has seen changes in recent years. In 2016, the university renovated its cultural centers and added a Cambus stop. Improvements at the Afro House included removing walls upstairs to create a large space for group activities and getting new furniture, oven, microwave, and commercial-grade picnic table for the yard.

Nelson says while recent changes have breathed new life into the space, there is one aspect in particular he would like to invest more in.

“One of the things I love about the other centers is they have murals and paintings all over,” Nelson says. “I love graffiti, and I’d love to find someone to do something dope on the upstairs white walls. How do we add other pieces of art that speak to all our students? I want the house to reflect all of the diaspora.”

Still necessary 50 years later

Reanna Lewis didn’t have a smooth transition to life at the University of Iowa.

Lewis, a first-generation student who transferred to Iowa from Los Angeles, sought a sense of belonging upon her arrival. She encountered racism throughout her first two semesters. “This is something I expect in the real world; I quickly realized that there would be no exception just because I was at college,” Lewis says.

At one point, she withdrew from school for a semester in order to get counseling and recover from her experience.

“[The Afro House] was created because there was a lack of presence; we needed something. We may not be as politically charged as we once were, but we were and remain a resource. What I hope students do, what I push students to do, is use it as a hub, or a space where everyone knows they can come to this spot. And I see students do that.”

Now, Lewis (a.k.a. “Lochemet Perach”) is again enrolled at Iowa, majoring in English and creative writing and serving as editor in chief of B.A.R.S. (Black Art; Real Stories). She found the confidence to return to school thanks to the Afro House, which she describes as “the only place on the University of Iowa campus where I can go and feel somewhat at home.”

“When I go to the Afro House, I can express my pain and have it taken seriously,” Lewis says. “I can laugh without worrying about when it’s going to be interrupted or stopped. I can have deep conversations without my intelligence being taken as a surprise. I can spit (rap) and not just be seen as a form of entertainment but an individual.

“When I’m in the Afro House, I don’t just exist—I am my most beautiful and authentic self,” she adds.

It is frustrating to endure wildly inappropriate requests. Lewis recounts having others wanting to touch her hair because of the way she wears it—something Lewis equates to being “touched like a pet.” The community and resources found at the Afro House provide Lewis with the strength to persevere.

“The Afro House reminds me that the struggles I have faced and still face as a black student on a predominantly white campus, in a predominantly white city, have done nothing but equipped me to continue to strive for greatness,” Lewis says.

For Nate Robinson, the Afro House was crucial in the development of his identity.

Robinson grew up in Woodridge, Illinois, a predominantly white community. (In that sense, the University of Iowa felt familiar.) Throughout his childhood, Robinson never felt “black enough.” People constantly told him he “talked white,” and he had the Oreo label lobbed at him. At the same time, he had notions of the sort of black that he was—and that there was another sort of black that wasn’t to be imitated.

“It is a source of pressure, dealing with that question of identity,” Robinson says.

The weekend before his first semester started, Robinson was introduced to several campus resources, the Afro House being one of them. The summer cookout he attended had no shortage of good food, good music, and fun games, and he was surrounded by faces that resembled his own. He soon discovered the house’s programming, which led to an examination of his identity and the larger issues around it.

“Engaging in those discussions on identity was incredibly helpful,” Robinson says. “Black has no strict definition. How I talk is not a resemblance of my identity—it’s simply a dialect. I was able to learn more about myself personally.”

One such realization: he’s always been a leader. Not long after setting foot on campus, Robinson filled leadership roles in black organizations, including the prestigious Hubbard Scholars. In this role, Robinson helped create the first Black Male Retreat, a weekend-long program held at the Afro House in fall 2017. There, students focused on identity, mental health, and other issues one might not consider common topics of conversation between black men.

“That is one of my favorite memories of my time here at the university,” Robinson says. “The bonding that happened, the memories we created—the brotherhood was real.”

Robinson, who will graduate in May and aspires to attend law school and run for public office, hopes future generations of UI students are able to have even greater opportunities at the Afro House, a resource he sees as necessary.

“When a small percentage of the student population identifies a certain way—in this case, as black—there needs to be spaces like this to connect,” Robinson says. “It could be so easy to feel lost. Dealing with microaggressions is a reality. You need a place to go to just be you. Iowa is making great strides—let’s continue to advance it.”

Wiggins, meanwhile, says she is always trying to work herself out of a job.

“We’re seen as experts on blackness, but I look for the time when we can all be experts on social justice and accessibility,” Wiggins says. “Or when every building is a multicultural center. For example, there’s no reason EPB (English-Philosophy Building) can’t show black writers or Chicano writers throughout the building.”

Nelson says he’d love for the centers to become museums, not needed as a hub but to instead preserve a piece of university history.

“I wish I wasn’t necessary,” Nelson says. “I want my black students to feel comfortable in the classroom or cafeteria and not feel like people are watching or judging what they say and do. I want to make sure racism is stomped out and to make sure we have resources for students to move forward.”

To realize their visions, Wiggins and Nelson both agree that the university needs to increase minority student enrollment and recruit and retain more minority faculty members. They also would like to see more training for faculty to better navigate issues of race.

“I want to challenge faculty to learn how to tackle difficult discussions,” Nelson says. “If a student sees or hears something, faculty should feel comfortable stepping in. I appreciate the faculty who already do this, but we need resources to teach more.”

Mitchell, who helped design various materials for the African American Cultural Center’s 50th anniversary, says she would like to see more people take time to understand where other people are coming from when engaged in conversations of race and ethnicity.

“We need to not be afraid to reach out to one another and make friends,” Mitchell says. “People put up walls because of stereotypes they have in their mind. In order to really grow as a community, you have to let those walls down. And people need to speak up against racist behavior and speech when they see it and hear it from friends and family.”

Shivers says the UI has made a start in improving the culture on campus, but there is much yet to do, including in the cultural and resource centers. In a recent survey, students called out the centers as important in recruiting and retaining students. However, they noted the centers need to be more visible and accessible—particularly on campus tours.

“We have to continue to invest in them,” Shivers says. “If we want the have the cultural centers on the admission tours, we want to make sure the spaces they visit are as vibrant and engaging as possible. We need to continue to care for all of our cultural and resource centers in pretty significant ways. I think we’ve done some good work in terms of sprucing them up, but there’s still a lot yet to come, and I look forward to being here to demonstrate that investment.”

One piece of the narrative surrounding the Afro House sometimes is not recognized, Shivers and Wiggins say, and that’s that everyone is welcome.

“There’s a dual purpose to the Afro House,” Wiggins says. “Number one—and this is central to its identity—is to support students of color. But the second purpose is to say, ‘This is what blackness is, or what it could be—not that it’s monolithic.’ This is a place you can come and learn and explore—not in a fetishizing type way, but in an academic sense. It’s open to all students, and that sometimes gets lost in the messaging. Our mission is to offer programming around black students, but anyone is open to come any day of the week.”

As for Berry, she says she thinks there will always be a need on campuses for places based on difference, whether it’s race, ethnicity, gender, ability, or age. And differences are certain to evolve over the years.

“I don’t know if we’ll ever be a fully integrated society, and I don’t know if we need to be,” Berry says. “I like who I am and I don’t need to be someone else. We’ll always need spaces for difference to thrive. We just need to respect and support and care about each other.

“I may not go to the Afro House every day or to all the events,” Berry adds. “I may not use it the way I maybe should as a faculty member, but it’s just nice to know it’s there. It gives me some comfort, and it makes me feel supported, even as faculty. It needs to be there.”