The Blaschkas’ glass menagerie

Hometown: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Area of study: Whitman is an MFA candidate in studio art with emphases in sculpture and photography.

Summer research plans: To photograph and create a catalogue and database for the 552 Blaschka models at the National Museum of Ireland–Natural History in Dublin.

Funding:

- School of Art and Art history International Research Travel Grant

- UI Graduate College Research Fellowship

- Eve Drewelowe Scholarship for International Research

In the late 1800s, a father and son created a glass menagerie of small, rarely seen marine invertebrates. Every detail and color perfectly replicated, these objects became some of the world’s most delicate scientific tools. However, emerging technology seemingly rendered the models obsolete.

A longtime scuba diver and environmental advocate, Jacquelyn Dale (JD) Whitman is infatuated with marine life. She’s also an artist pursuing an MFA in studio art with two primary emphases in sculpture and photography, and a secondary emphasis in intermedia at the University of Iowa. While conducting research in Ireland on a UI Stanley Graduate Award for International Research during the summer of 2016, Whitman stumbled upon a newspaper article about the long-forgotten artifacts from the 1800s, which led her on a journey that merges her two passions.

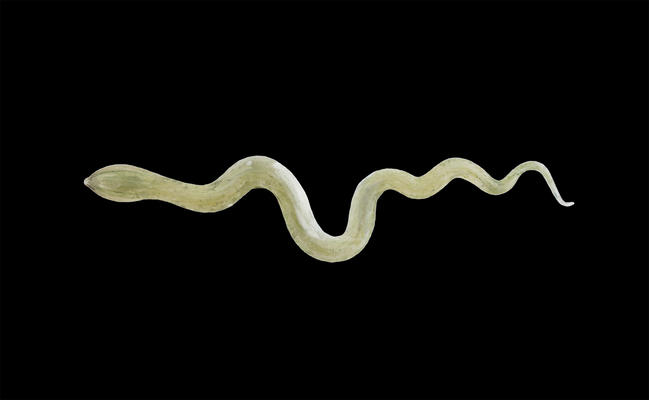

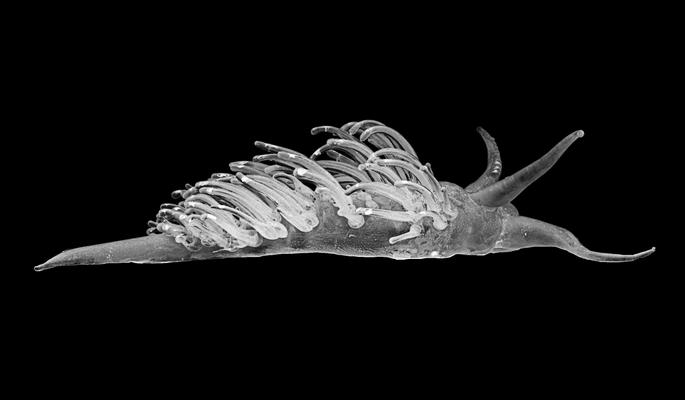

In the 1800s, marine invertebrates—animals that do not have a spinal column or backbone, such as starfish, coral, and crabs—were difficult to study because they could not be preserved using taxidermy or formaldehyde processes.

“If you wanted to study them, you had to capture them and look at them in real life,” Whitman says. “Or you could do what Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka did.”

From their glassmaking studio in Dresden, Germany, the craftsmen created exact replicas of thousands of marine invertebrates, which were sent to museums and universities around the globe to help people learn about the creatures. But as underwater photography became commonplace, the glass models were no longer needed.

“They were put on shelves and forgotten,” Whitman says.

As it turned out, one of the largest known collections of Blaschka models—556 of them—were housed at the National Museum of Ireland–Natural History in Dublin. The objects weren’t on display to the public, but Whitman talked Nigel Monaghan, keeper of the National Museum Ireland–Natural History Division and longtime Blaschka enthusiast, into letting her see them.

“It’s a call to look at how beautiful and important these creatures are to marine ecosystems. Some of them are now extinct, but we can learn and work to save the ones that remain.”

“They were in the same cabinets they were initially put into at their acquisition during the Victorian era,” Whitman says. “I thought, ‘People have to see these incredible objects.’”

The museum had begun photographing the collection but didn’t have a complete database of the models. Whitman made the museum an offer: If she raised the money, would the museum let her photograph each Blaschka model to work toward the creation of a digital catalog that could be used for research purposes and one day be available online for the public to see? The museum agreed, and Whitman spent the next year writing dozens of grants.

“I don’t think they believed me when I said I’d do the grunt work and get the funding.” Whitman says. “They gave me the opportunity and I made it happen. I got obsessed and wouldn’t let go.”

Whitman says she believed so strongly in this project that she would have paid out of pocket to complete it, but says she was fortunate to not have to, due largely in part to research funding through the UI.

“I started writing grants before having the support of the university, and then went through the same process after having that support—the difference was night and day,” says Whitman, an MFA candidate in sculpture and photography. “People are much more receptive when you are backed by your institution. Having that support made a huge difference.”

Whitman returned to Dublin in summer 2017 to begin the project. One of the first steps was to develop standardized methods for photographing each model to help researchers and conservators investigate the structural components, materials, and state of each model.

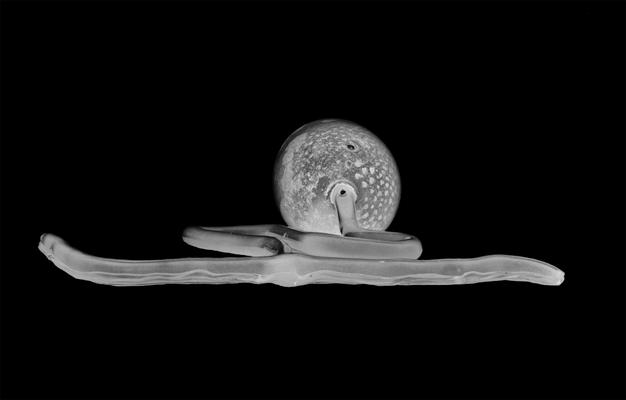

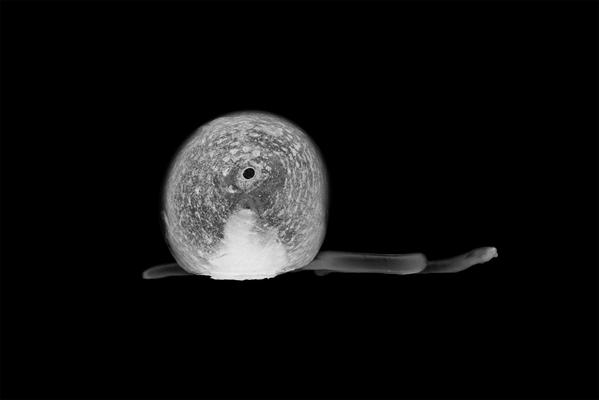

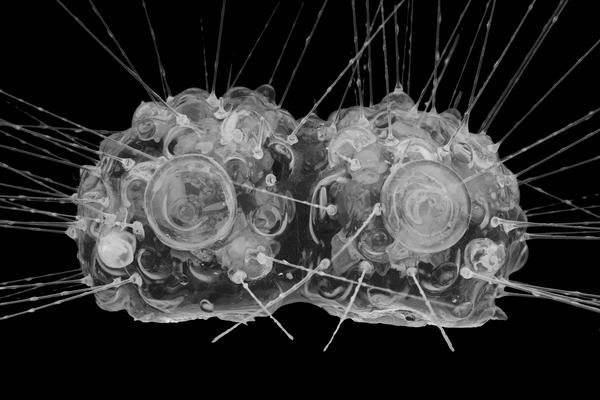

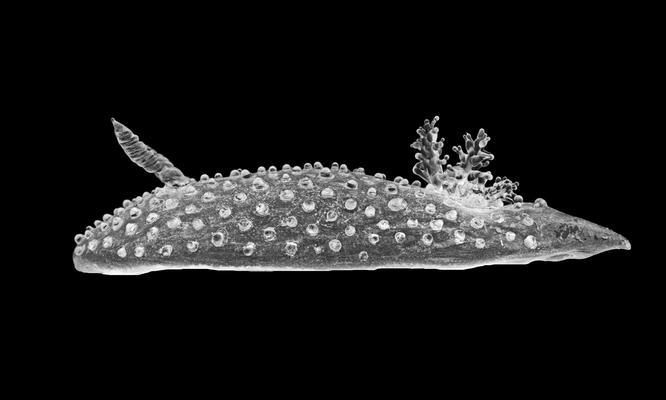

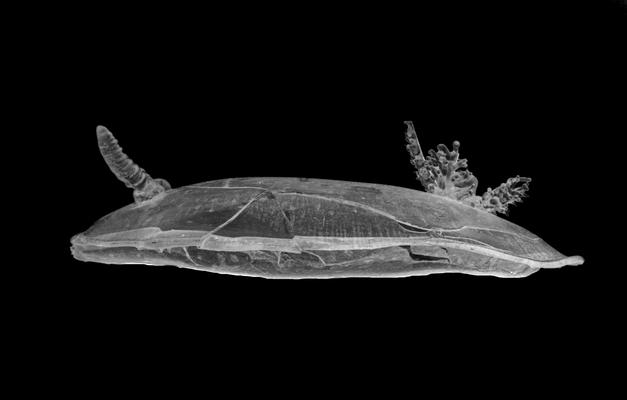

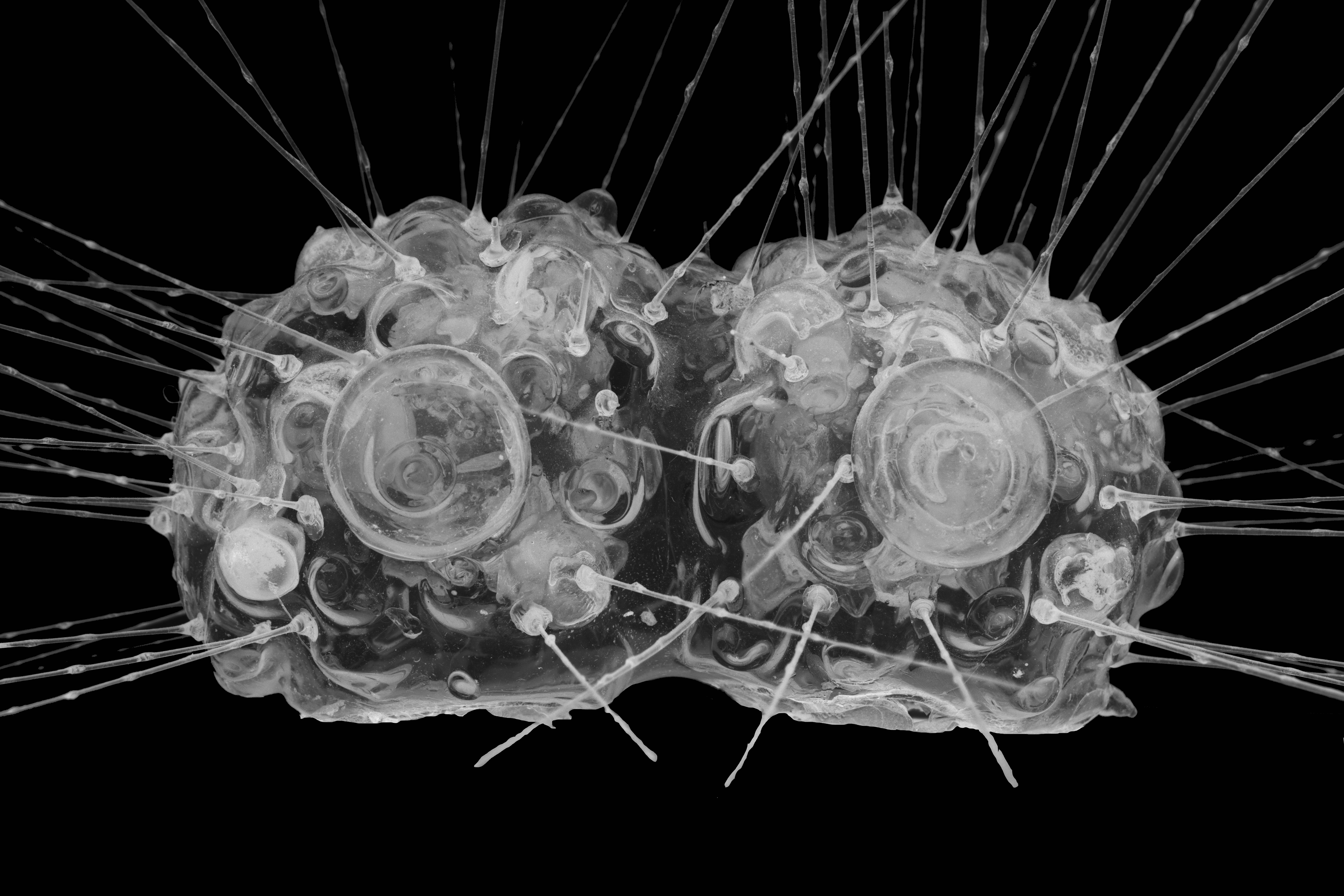

To sculpt the glass models, the Blaschkas incorporated layers of wire, resin, wax, fabric, paper, paint, and other materials that are still being discovered and investigated. In order to more clearly see these internal details, Whitman creates inverted images out of backlit photos, equivalent to an X-ray of the object. Being able to know which elements each model contains also helps determine how best to care for it.

“They are all one of a kind and need to be preserved in different ways,” Whitman says.

Whitman documented 114 of the 556 models in summer 2017. This summer, she is working with a team of volunteers and curators from the museum, and her goal is to catalog as many of the remaining models as possible.

Whitman says the Blaschka models traditionally have been seen as scientific tools and not as art. However, she thinks they are both—and that they are just as important today as they were in the 19th century.

“What interests me is that because of their exactitude, they are a record of biodiversity at that point in time, as well as a record of a decline in biodiversity since,” Whitman says. “But they are also incredible works of art. Glass artists today can’t figure out how they were made. People have tried to replicate them and can’t. This father-and-son team were experimenting and doing amazing handheld flame work. This summer, after extensive research, we are only just discovering various materials and methods used for construction.”

Whitman’s work with the Blaschka models also has influenced her own art and research, which focuses on educating the community about threats to our ocean through art. The museum allowed her to use the photographs in her own artwork, primarily interactive sculpture installations made from recycled plastic. As part of her MFA thesis, Whitman animated photos of the Blaschka models to show how the species would have moved and currently move in their oceanic environments. She then projected the animations onto the installations, which people could walk through.

“It’s a call to look at how beautiful and important these creatures are to marine ecosystems,” Whitman says. “some of them are now extinct, but we can learn and work to save the ones that remain.”

Steve McGuire, professor of metal arts and 3-D design and director of the UI School of Art and Art History, says Whitman recognizes that educational engagement is critical to the fields of art and science, and that she is passionate about finding ways to incorporate it into her work.

“She’s very interested in how art and science can come together to strengthen each other,” McGuire says. “When she makes artwork about scientific topics, she’s giving a picture that can’t be made any other way.”

The Blaschka models have endured for more than a century and are enjoying a recent resurgence in popularity. Whitman says she is happy to be a part of bringing renewed attention to them.

“There’s this whole community that feels the same way I do and is just as obsessed as I am,” Whitman says.

Scientists are looking at Blaschka collections around the world as time capsules, documenting which creatures are still living in the oceans and how they are faring in today’s ecosystems. Artists and conservators are studying how the glass models were created and how they can be protected.

In fact, Whitman isn’t the only person working with the collection in Dublin. She’s worked closely with Emmanuel Reynaud, a lecturer/assistant professor in the School of Biomolecular and Biomedical Science at University College Dublin, who is spearheading the research, resurgence, and preservation of all Blaschka models owned by multiple institutions across Ireland.

Whitman hopes the increased interest will result in increased funding to help with their preservation and one day make them again available public viewing.

“They really need their own museum,” Whitman says.

University of Iowa art students travel the world in pursuit of discovery.