Filtering Flint’s backroom chatter

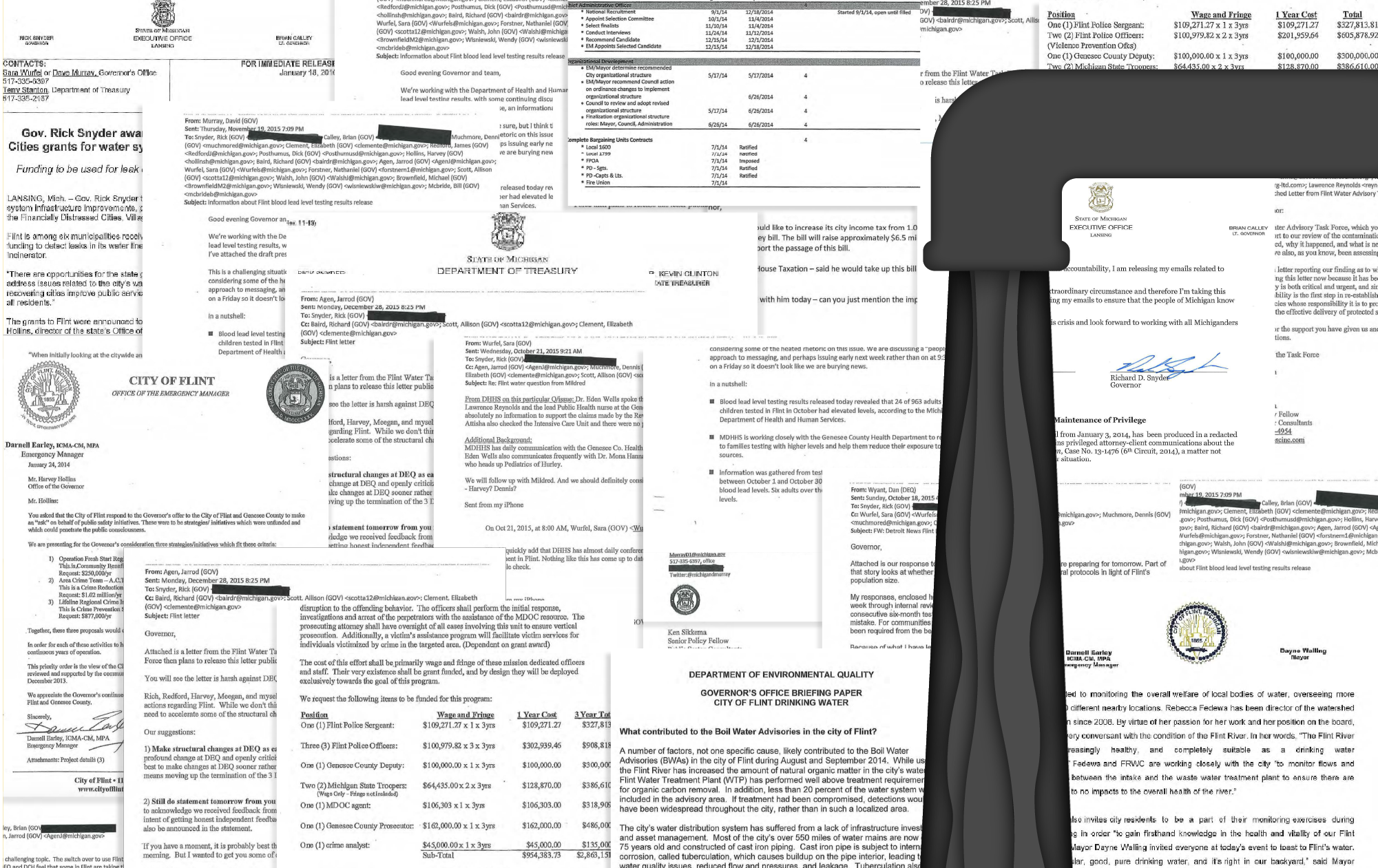

In 2016, nearly a half-million pages of emails from Michigan officials in a variety of state departments and agencies related to the Flint water crisis were released to the public.

Since then, journalists, residents, and investigators have pored over thousands of discussions regarding aging pipes releasing lead into the city’s drinking water. But it’s a difficult task. The documents are PDFs and the ability to easily search and sort them is limited.

A group of faculty, staff, and students at the University of Iowa is trying to make the documents more accessible and usable for those they affect, as well as for future researchers.

“This project is crucial for a lot of reasons,” says Louise Seamster, an assistant professor with dual appointments in the Department of Sociology and Criminology and African American Studies. “For one, these emails reveal the backroom of decision-making and the process of deciding who to listen to. We don’t always have this backroom access of what was actually said and how that shaped the decisions that were made.”

“It’s important for this information to be available to the public because it can prevent future incidents like this. It also illustrates how emergency management laws can disenfranchise and affect majority Black cities and shows that there are still systemic problems in this country. Hopefully it will also help provide justice for what happened in Flint.”

Seamster has been studying racial politics in Michigan since 2012, and started using the emails in 2017 with her students at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

“But one thing that was clear was that I needed more of a technology interface to let students get their hands on the data quicker,” Seamster says. “I’ve been able to put a lot more into this research since I got to Iowa thanks to the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio.”

Matthew Butler, senior developer for the studio, has been working with Seamster and her students since 2019. He has served as a liaison with IT units to administer database servers on and off campus, and more recently has been building software to help analyze, annotate, and categorize individual files in the dataset. He also has been training students in the Python programming language and Anaconda data science platform.

“I’m delighted to help scholars and students combine a passion for their research topics with technical skills acquired ‘on the job,’” Butler says. “It’s a potent combination of theory and practice, in my opinion. Projects such as this give undergraduates in particular the opportunity to work on real-world problems in a meaningful and hopefully fulfilling way.”

Louise Seamster, assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminology, says making nearly a half-million emails related to the Flint water crisis more easily usable for the public wouldn’t be possible without the partnership of the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio.

“Coming to Iowa where there’s a 14-person studio and resources and physical space made such a difference,” Seamster says. “When I first met with them, I thought I was just telling them about a project I was trying to do. And then they said, ‘OK. This is something we help with.’ I was just blown away.”

Seamster says the studio also pointed her in the direction of grants that could help fund her research and lab, such as the Arts and Humanities Initiative Program and Innovations in Teaching with Technology Awards.

“They help with everything that is beyond my training, and are teaching me along with the students,” Seamster says.

Thanks in part to grants from the Arts and Humanities Initiative Program, Innovations in Teaching with Technology Awards, and Public Policy Center, Seamster started the Flint Email Lab. Research fellows in the lab, among other things, are cleaning data, testing the database, and producing training material and workflows that are being used in an applied research class this spring.

Terry Saul III took one of Seamster’s courses in spring 2020, during which the two discovered a shared interest in emergency financial management and the health outcomes it can affect. Seamster asked Saul—a fourth-year student working toward a BA in interdepartmental studies (business studies track with a focus on ethics and values) and a philosophy minor—if he would be interested in participating in the research. Saul is now a research fellow for the Public Policy Center and student mentor for the class.

One of Saul’s main projects over the past year involved researching the individuals in the emails and the roles they played within the government organizations. He’s identified 957 individuals and used data visualization to structure the emails to illustrate the network of communication.

“It’s important for this information to be available to the public because it can prevent future incidents like this,” says Saul, who graduated from high school in Bettendorf, Iowa. “It also illustrates how emergency management laws can disenfranchise and affect majority Black cities and shows that there are still systemic problems in this country. Hopefully it will also help provide justice for what happened in Flint.”

Hannah Zadeh had read some of Seamster’s previous research and emailed her to learn more. The fourth-year student pursuing a BA in sociology on the pre-medical track is now an undergraduate research assistant in the Flint Email Lab and a student mentor for the class. After training with Butler, she has taken the lead as developer of a suite of text analysis programs.

“I’ve had research experiences before, but nothing like this,” says Zadeh, who grew up in Ankeny, Iowa. “I can really see the impact this can have. Despite having so much available information, few people have the time and resources to explore it easily. This is one reason people in power are protected and not held accountable. We are making this huge amount of data accessible.”

One of the goals of this semester’s applied research class is to use qualitative coding and machine learning to code each email as formal or informal.

“The idea is that once you’ve coded the emails as formal and informal, you can map out a communication network of who is talking to whom over time,” Seamster says. “Knowing the formality with which people were talking to each other can illustrate the tight-knit networks of people on the inside who were at times joking with each other about the situation as compared to how they were talking to other parties. It also sets up the opportunity to do more in-depth qualitative coding later.”

Along with such practical tasks, Seamster says the class also is examining the bigger issues and different approaches to such research: “We’ve been thinking about ethical questions such as ‘Which data can we access?’ “Who does it belong to?’ Just as there’s a lot more data out there now, there’s a lot of discussion around who has whose data and what are they allowed to do with it. And this is a great project to start raising some of those questions.”

Along with wanting to make the class accessible to students no matter their technical experience, Seamster says she wanted to inspire confidence in her students to dream big and not let obstacles derail their goals.

“Hopefully this shows them that something as daunting as a half-million pages worth of PDFs shouldn’t stop them from exploring a topic that interests them. They can make it usable—and there are people out there who can help,” Seamster says. “I’ve already seen a lot more ambitiousness in the students. They are telling me they are glad they decided to challenge themselves and that they have a greater understanding of what they are capable of.”

Butler says he hopes the students realize that computer programming and data analytics are tools well within their reach.

“In the past I’ve had a bit of impostor syndrome. But having the opportunity to contribute and feeling like my input is valued has been really meaningful to me.”

“While this is only one component of the project, they should feel proud they have tackled a complex and challenging problem using technical skills learned in response to each hurdle,” Butler says.

Zadeh says being a part of the project has given her a lot more confidence in her abilities as a researcher.

“In the past I’ve had a bit of impostor syndrome,” she says. “But having the opportunity to contribute and feeling like my input is valued has been really meaningful to me.”

Saul says the skills he has gained—such as those in Python and data visualization, along with advanced analytics and presentation skills—will serve him well in the future. He also attributes his experience to helping land a research fellowship position at Indiana University, where he’ll be starting grad school in the fall.

“This project really sparked my interest in research,” Saul says. “I never imagined I’d be a part of anything like this. It’s truly been a gift, and I’m grateful for it. I hope more students pursue similar opportunities because it’s so beneficial.”

Students in the lab and class come from a variety of disciplines, including sociology, business, public health, rhetoric, and journalism.

Participating in life-changing research isn’t just reserved for graduate students. Thirty percent of Iowa undergrads conduct or assist with research. The Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates helps undergraduates find research and creative work experiences, facilitates mentorship, and provides platforms for students to learn research communication skills.

“Some people are intrigued by the idea of using linguistics and thinking about syntax, while others are interested in the policy angle,” Seamster says. “This type of collective learning model works so well. The students share skills with each other, find new interests, and realize they can be part of something bigger.”

Saul says working with people from different cultural and educational backgrounds has made the team stronger, allowing them to tackle problems from different perspectives and land on the best strategies to use going forward.

“Coming from a business background, I’m used to looking at systems and structures. But working with people who have a sociology background taught me to really look at the people and the way they think,” Saul says. “It’s really opened up my mind and expanded the way I look at things.”

The team has primarily worked remotely because of COVID-19, but Zadeh says that hasn’t affected the team dynamic.

“I recently realized I haven’t met many of our team members in person,” she says. “It’s cool to know that it’s possible to build a great team even when we have to be online.”

As the semester progresses, students are examining other crowdsourced citizen-science projects and making suggestions for how future iterations of the tool being developed at Iowa can be improved to better allow people in the future to engage with the Flint emails.

Seamster is applying for grants to fund longer-term research, and the team hopes to have an initial version of the website online by the end of 2021.

“Even though national media attention has to some extent moved on from Flint, the story isn’t over,” Seamster says, citing multiple criminal charges that have been filed in connection with the water crisis. “There is still a lot of information in these documents to mine, and a lot of things we and the residents of Flint still don’t know about.”