Neuroscience student finds perfect match at Iowa

Matthew McGregor came to the University of Iowa for graduate school because he found a perfect match.

McGregor graduated from the State University of New York at Buffalo with a degree in biomedical engineering. Along his undergraduate route, he discovered an interest in the human brain and how the mind’s actions dictate behavior. So, when it came time to consider graduate schools, McGregor sought researchers and programs that suited his newfound passion.

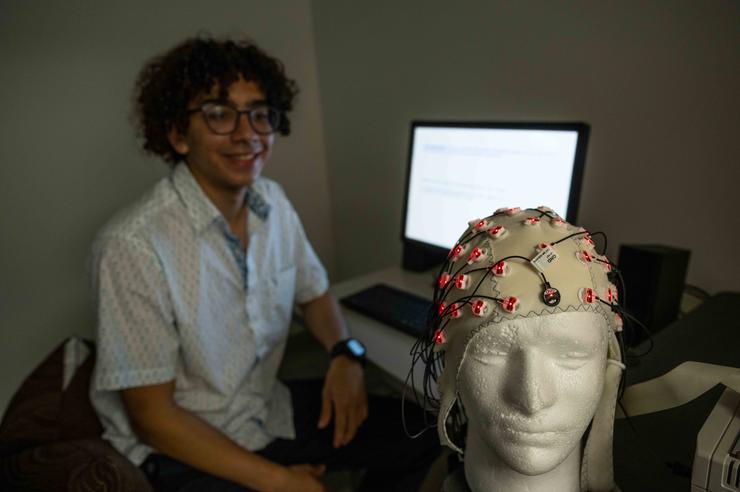

As he researched graduate schools, McGregor, who’s from Fairport, New York (outside Rochester), read some scientific papers from Ryan LaLumiere, associate professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Iowa. McGregor learned LaLumiere studied the neurobiology of learning and memory, as well as the brain’s role in addiction and relapse. Moreover, LaLumiere’s research group used a technique—relatively new at the time—called optogenetics, which employs light to study activity in the brain in real time.

“His research matched my interests at the time, and he used optogenetics,” McGregor says.

McGregor visited campus in February “on a brutally cold weekend,” as he recalls. But the warmth from the faculty and the welcoming environment in the department took the physical chill away.

“I had good interactions with current students and faculty, including Ryan. I was like, ‘OK, yeah, I could see myself here.’

“It was important to me that there was a sense of community within the graduate program,” adds McGregor, now a student in the Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Neuroscience. “I know some other graduate programs don’t really have that community. You affiliate with a lab, and you just stick to that lab. There’s little interaction outside the lab program, unless you actively seek it. But just from my interview weekend, it was very clear to me that this was a program that was more than an organizational sense or a namesake. This is a program that makes an effort to build a community.”

The Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust has committed a transformational $45 million grant to the University of Iowa that allowed for the creation of a comprehensive and cross-disciplinary neuroscience center within the Carver College of Medicine. Led by Ted Abel, PhD, the Iowa Neuroscience Institute conducts research to find the causes of—and preventions, treatments, and cures for—the many diseases that affect the brain and nervous system.

LaLumiere recalls meeting McGregor and being impressed by how he clearly articulated the ideas he wanted to investigate.

“A lot of graduate students come in with interests in vague, general areas,” says LaLumiere, also a member of the Iowa Neuroscience Institute. “Matthew wasn’t like that. He had very specific interests and knew about topics in a much more concrete way.”

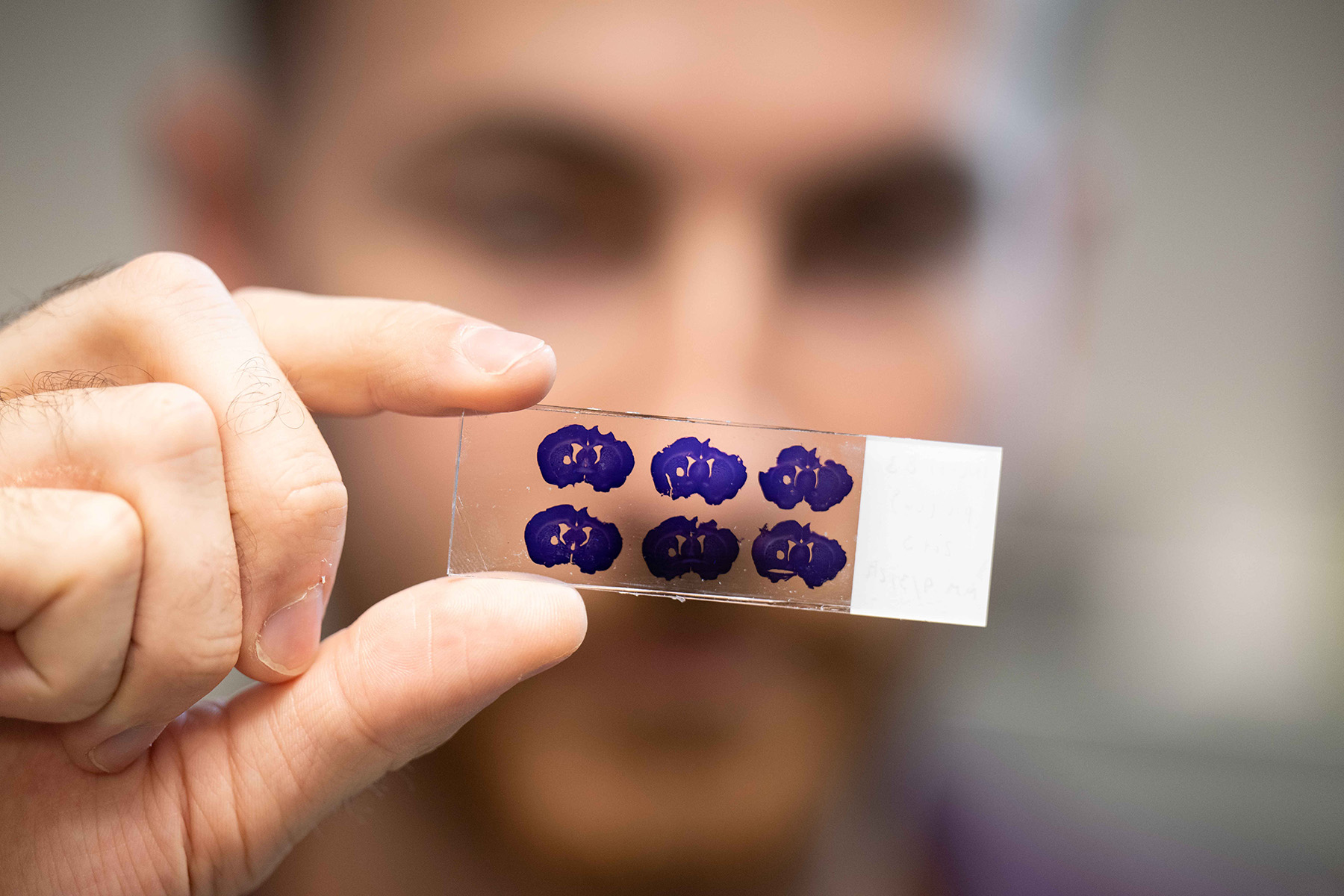

McGregor began studying the brain’s role in learning and memory but switched to addiction and relapse research as funding became available. He traces his interest in part to reading a 2006 paper, published in the journal Science, in which researchers at Iowa and the University of Southern California noticed that patients with damage to a brain region called the insular cortex were able to quit their smoking habit on a dime.

“I realized this could be a region that is responsible for drug addiction and could be used as a target for treating drug addiction,” McGregor says.

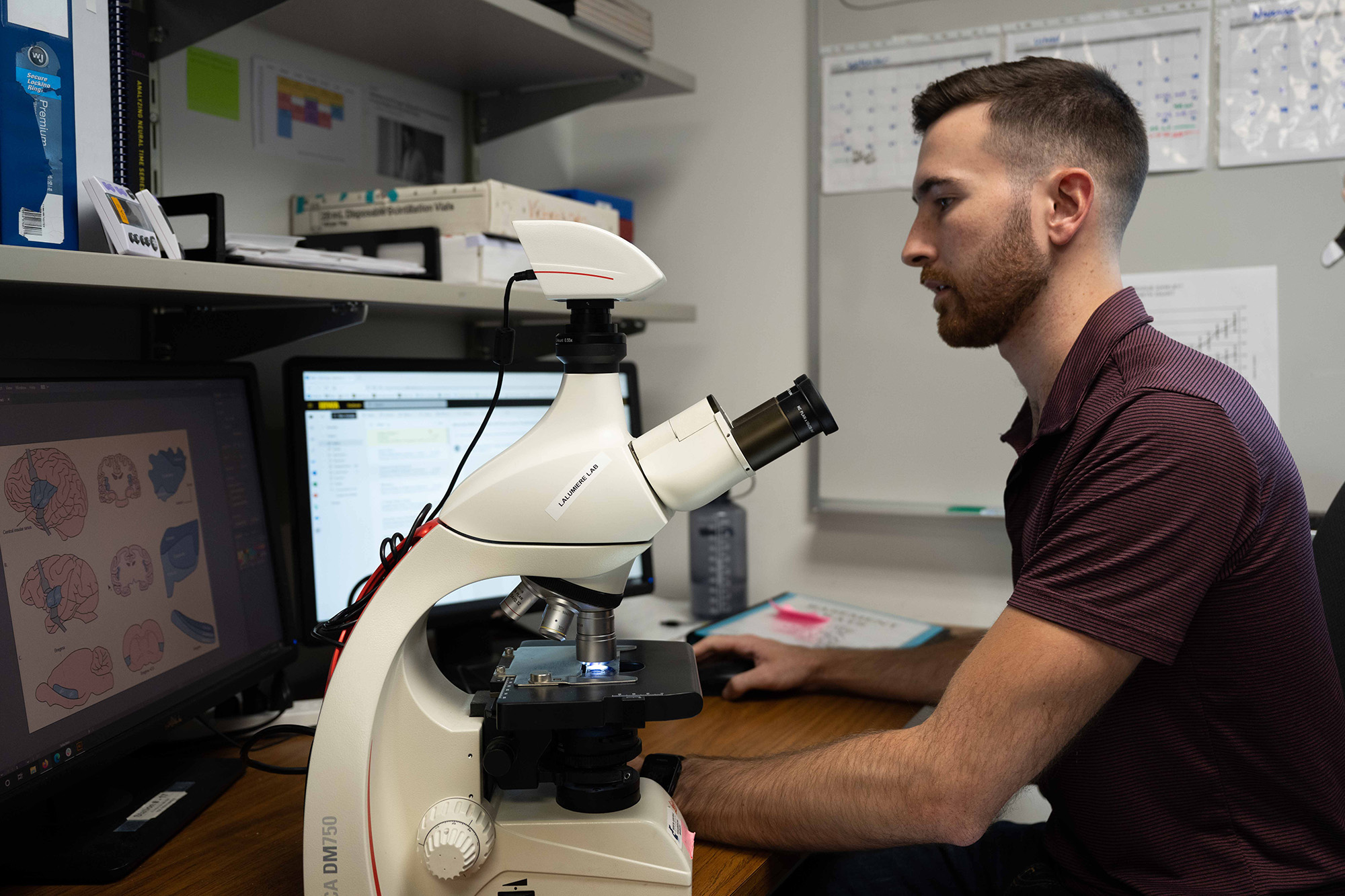

Like other graduate students well into their doctoral studies, McGregor runs his own research line in the LaLumiere group. In particular, he wants to understand more fully how, and why, the insular cortex is involved in addiction and with powerful emotions governed by the mind, such as withdrawal and relapse. To untangle the neural connections, he examines the brains of living rats that become addicted, undergo withdrawal, and are reintroduced to the addictive substance. The idea is to observe the rats’ brain activity and physical behavior at various stages of addiction, withdrawal and relapse, and compare that with rats not part of the addiction and relapse cycle.

“Part of what I’m trying to figure out is the bundles of neurons and pathways from the insular cortex to other brain regions that are involved in drug-seeking behavior,” McGregor explains, “and the neurons and pathways that could be involved in inhibiting that behavior.”

“It was important to me that there was a sense of community within the graduate program at Iowa. Just from my interview weekend, it was very clear to me that this was a program that was more than an organizational sense or a namesake. This is a program that makes an effort to build a community.”

McGregor also enjoys the freedom of being able to pursue his own research questions.

“I’m in charge of my experiments,” he says, “and when things go wrong, I’m in charge of figuring out how to fix them.”

LaLumiere says McGregor’s research has advanced understanding of the brain’s involvement in substance addiction and relapse, with published results expected soon.

“We have to acknowledge he was here during the pandemic, and that slowed down everyone’s progress in research,” says LaLumiere, who has four doctoral students in his research group. “Nonetheless, he’s been doing a great job progressing. He’s leading experiments from A to Z, and that’s what I expect from doctoral students at this point in graduate training.”

If all goes as planned, McGregor will earn his doctorate in spring 2025. After that, he plans to enter industry, testing promising anti-addiction medications on animals for their efficacy, health and safety, and possible side effects.

He says a big motivator is being a scientist who can concentrate full time on work he feels is important to society.

“My desire to pursue industry rather than academia has more to do with the kinds of roles that scientists have in industry,” McGregor says. “For me, I don’t enjoy the grant writing and application process. I do enjoy doing the science—being on the bench, rather than the desk, so to say.”