Revealing a medieval Gothic cathedral’s mysteries

Hometown: Media, Pennsylvania

Area of study: Smith received her PhD in art history from the UI in May. She will start her job as instructor of art history at Wake Tech Community College in Raleigh, North Carolina, in the fall.

Summer research plans: To conduct a laser scan of the interior and exterior of Reims Cathedral in Reims, France. She will be joined by Robert Bork, UI professor of art history, and Adam Skibbe, GIS administrator in the UI Department of Geographical and Sustainability Sciences.

Funding:

Rebecca Smith spent the fall 2015 semester measuring Reims Cathedral in Reims, France, armed with tools not much more advanced than those used when construction on the cathedral began in 1211. In August, she will take a much more high-tech approach to studying the impressive example of medieval Gothic architecture.

The Philadelphia-area native who in May received her PhD in art history from the University of Iowa has taken a particular interest in medieval Gothic architecture and design, the role of geometry in architectural design, and the interaction between design and structure in buildings. Her dissertation, “Measuring the Past: The Geometry of Reims Cathedral,” examines the underlying geometry dictating the cathedral’s design and whether the final plan for the whole building was established by its initial architect or modified over the course of construction. (Medieval cathedrals often took decades to complete.)

This will be Smith’s fourth trip to Reims Cathedral, during which she will use a sophisticated laser scanner to conduct the most comprehensive survey of the building yet. The cathedral, which was the traditional site of coronation for French kings, is considered one of the world’s defining models of Gothic art.

“It will be exciting,” Smith says. “No one has made a full scan of Reims Cathedral. It’s such an important building that it’s astonishing no one has done it yet. This will fill in a big gap for laser scanning of cathedrals.”

Smith’s first attempt to measure the building in 2015 was not quite as advanced.

“I spent months crawling around the cathedral with a ruler, measuring the building by hand,” Smith says. “I made all these really precise drawings and tried to document the different specifications and dimensions of all the piers and the main widths of the building. I had a very small laser, but the bulk of the work was done by hand.”

During her next trip in summer 2016, she borrowed a laser that had just come on the market from Robert Bork, a UI professor of art history. A laser scanner uses laser beams to measure distance and record geometrical information about an object or surface in its field of view. The laser that Smith used took a limited set of selected data points—about 30. While the scanning process was relatively easy, Smith then had to stitch the sets together to create a model of the building.

“Rebecca is leveraging engineering and new technology to reimagine an entire field in terms of medieval architecture. She can reveal things that just were not able to be seen before. And with that, she can give a reappraisal of the cathedral, which is pretty significant.”

“It took forever,” Smith says. “It was the worst 3-D jigsaw puzzle of all time.”

While acquiring the data was time-consuming, Smith eventually was able to use it to map the geometry of the building and compare it to the math.

“In some cases, things were within a half-centimeter of what we would expect, so there’s no doubt about it that it was perfect; everything went right in that part of the building,” Smith says. “But in other parts, there were major shifts. In those cases, we can look at what happened during construction to deviate from the plan.”

While the laser scanner Smith used on that trip was light-years ahead of her ruler and pencil, it only mapped the main elements of the cathedral. Smith now wants to make a full scan of the building, including the stained-glass windows, sculptures, and objects that were too minute to factor into the initial scan.

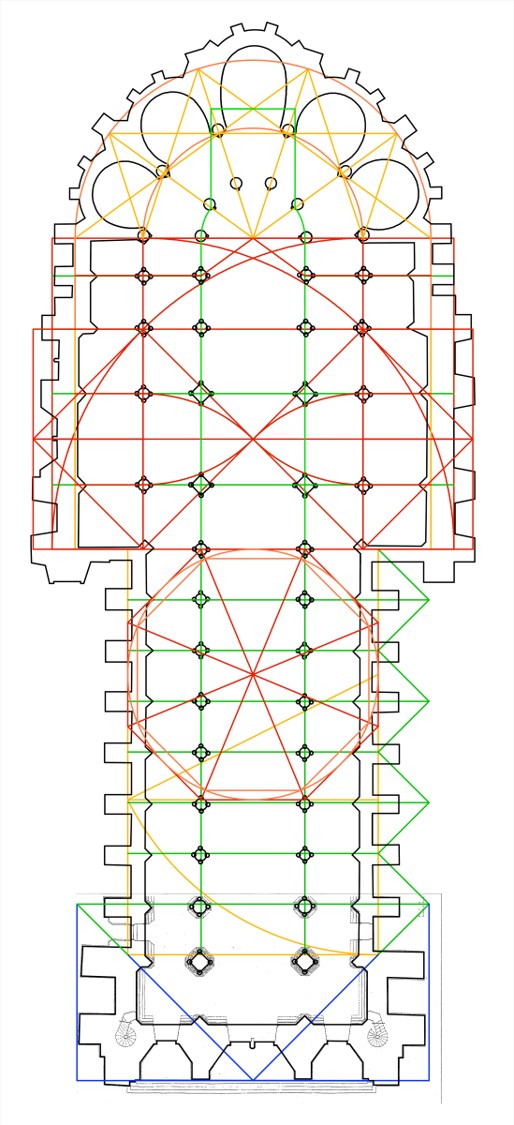

This geometric analysis of Reims Cathedral in Reims, France, was created in 2016 by Rebecca Smith using a small laser scanner. Smith, who received her PhD from the University of Iowa in May 2018, is returning this summer with a much more advanced laser scanner to create the most comprehensive 3-D survey of the cathedral to date. Photo courtesy of Rebecca Smith and Robert Bork.

“Cathedrals are planned so that all elements work together—sculpture, glass, everything,” Smith says. “I’m interested to see if the geometry continues all the way through, and what impact some of the issues that arose during the construction of the building had on things like the sculptural program.”

To do this, Smith needed a more powerful laser scanner, one that can collect billions of data points instead of thousands. While the UI offered to let her borrow a bigger laser, the cost and logistics of getting it to France were daunting. Fortunately, a professor at the University of Liège in Liège, Belgium, who completed his postdoctoral work in geography at Iowa is helping Smith borrow one from his university.

This more advanced laser scanner sweeps over an area, sending out laser beams. It then measures the amount of time it takes for that beam to hit an object and bounce back to the scanner. This generates a cloud of data points that captures the shape of surfaces and objects to create a 3-D model.

Smith says it will take about 10 minutes to scan a section of the building and estimates it will take about six days to scan the entire building inside and out. She won’t be doing it alone, though. Bork, the UI professor of art history, and Adam Skibbe, GIS administrator in the UI Department of Geographical and Sustainability Sciences, will join her. They also will make a scan of Metz Cathedral in Metz, France, which—while taller—is a smaller building than Reims.

“Robert (Bork) and I are interested in different things,” Smith says. “I’m fascinated in what happens after the plan is set and while they are putting the building up. He’s much more interested in what happens before they start building, how they put the design together. But our interests complement each other.”

The results of the research will be made available to the public through the UI’s Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio. Officials at Reims Cathedral stipulated that the results be made public when they gave permission to do the scan, and Smith hopes the information will be a useful resource for students and scholars.

“We want to make this a tool for people to be able to look at the building layer by layer, or at cross-sections, to see what’s going on in terms of the construction, to see how the geometry works in the building, what’s dictating different things, and how things interact,” Smith says.

Steve McGuire, professor of metal arts and 3-D design and director of the UI School of Art and Art History, says Smith’s research is contributing greatly to her field.

“Rebecca is leveraging engineering and new technology to reimagine an entire field in terms of medieval architecture,” McGuire says. “She can reveal things that just were not able to be seen before. And with that, she can give a reappraisal of the cathedral, which is pretty significant.”

Smith also thinks these scans, whether on a small or large scale, prove that laser scans are useful for studying Gothic architecture.

“There are people who think they are neat, but that they don’t have a lot of research potential,” Smith says. “I think my work has proved otherwise because we used the scan to talk about what goes on in the history and design and get somewhere in terms of our understanding of the building.”

University of Iowa art students travel the world in pursuit of discovery.