Two University of Iowa medicine alumni met by chance while serving patients in one of the most remote environments on Earth.

Story: Celine Robins

Photography: courtesy of Isaiah Reeves and Jon Ahrendsen

Published: Feb. 23, 2024

Imagine you’re standing in the middle of a glacial expanse on the coast of Antarctica.

It’s a balmy minus 18 degrees Fahrenheit with windchill, but with your snug parka on, you can feel the sun doing its darndest to warm your cheeks. In the distance, the peak of Mount Erebus, the world’s southernmost active volcano, exhales an icy breath into the crisp blue sky. The frozen sea is beginning to break up for the summer, and seals dot the horizon, doing whatever it is that seals do.

If you could stand here all day and night, perfectly still, you would see the tireless sun circle around you, rolling along the horizon like your very own satellite.

This is the scene at McMurdo Station, Antarctica, the largest research station “on the ice” (as is the common parlance). The station supports a wide variety of research activities, from marine biology to climate science and volcanic geology, and since Oct. 24, it hasn’t seen a sunset.

“It can become a little bit of a circadian disruption,” Isaiah Reeves admits.

It was in this stark and beautiful landscape that University of Iowa graduates Reeves (20MD) and Jon Ahrendsen (82MD) met, as both were coincidentally stationed to serve the community of research scientists and support staff who come to McMurdo from across the globe.

Medical cases in Antarctica felt pretty typical to UI medicine alum Isaiah Reeves. “This strikes me as very similar to any urgent care or primary care clinic experience that I’ve had in the United States,” says Reeves. “There’s a lot of common colds, for example. There are not too many unique cases other than perhaps a little bit of cold exposure. But honestly, I grew up in Minnesota and trained in Iowa; I’ve seen farmers with frostbite in Iowa.”

Small-town Antarctica

Operated by the National Science Foundation’s U.S. Antarctic Program, McMurdo Station is 900 miles from the South Pole and a five- to eight-hour flight (depending on the aircraft) from the nearest city of Christchurch, New Zealand. Peak population, during the summer research season, is somewhere around 1,000 people.

“It’s a lot like a small town in Iowa,” says Ahrendsen.

Aside from the researchers, McMurdo is home to hundreds of plumbers, construction workers, carpenters, electricians, galley workers, and many other support staff who make it possible to sustain life in one of the remotest places on Earth.

“There are vastly more folks who are supporting the functioning of the station than there are actual scientists because of how much effort it takes to keep everything running,” Reeves says.

Reeves is in his fourth year of training in the University of Texas Medical Branch’s (UTMB) combined Aerospace and Internal Medicine Residency Program. Resident physicians in the program regularly rotate to McMurdo to gain experience in providing health care in an extreme environment—a proxy for the kind of work they will do in their careers caring for pilots, aircrew, and even astronauts.

“Aerospace medicine is probably best described as being under the field of preventive and occupational medicine,” Reeves says. “We learn during our residency the unique physiological changes that occur in both the aviation environment and in space. When we consider taking care of astronauts on the International Space Station or on the moon, for example, those are very far away, and we take care of them from Earth. So, it’s a lot of telemedicine. It’s figuring out how to use limited resources in an austere environment. Antarctica provides a really great analog for that because we have a lot of those same difficulties down here.”

Ahrendsen, who normally practices family medicine in Clarion, Iowa, came to the ice seeking adventure and a new challenge. During a 2016 trek to Everest Base Camp with the Wilderness Medical Society, he met a physician who was preparing to be the winter doctor at another U.S. Antarctic research station. The meeting piqued his curiosity, and he reached out to UTMB to inquire about how he could get involved.

“In May, I got an email back from them, and they said they had an opening between August and February. Was I interested? I said, ‘Yes. What do I have to do next?’” Ahrendsen says.

He arrived at McMurdo in August 2023 for a six-month stay. Reeves has since returned from his one-month rotation to continue residency training in Galveston.

Life on the ice

Day-to-day life in Antarctica is at once totally strange and strikingly familiar. Reeves and Ahrendsen’s typical working hours are 7:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., Monday through Saturday.

“Housing is pretty much like a college dorm,” Reeves says. “And then there’s one big central dining facility that everyone will come to for meals.”

Despite the remote location, the culinary offerings are surprisingly satisfying.

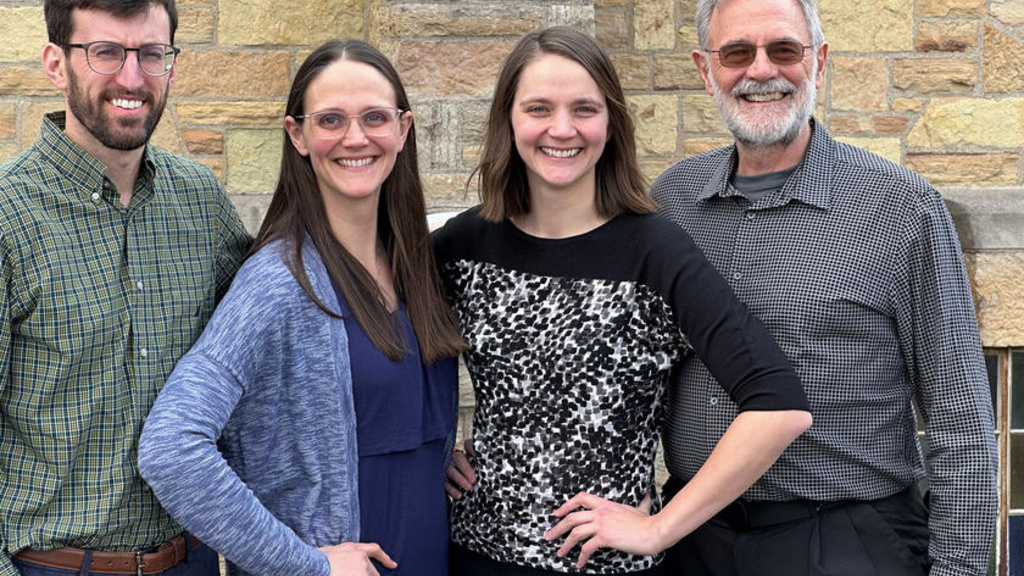

Family of doctors provide family care in rural Iowa

Four members of the Ahrendsen family graduated from the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine and now practice in Clarion and Storm Lake, Iowa.

“The food is wonderful. There’s always several choices, including vegetarian options at every meal,” says Ahrendsen. “Most people gain weight here.”

“They do fresh baked bread, as well,” Reeves adds.

Thanks to Starlink satellite capabilities, they even have moderate internet access—though its reliability can be a little spotty, as the writer of this article experienced during the 9,000-mile Zoom call from Iowa City to McMurdo Station.

“I have been able to listen to the Iowa football games streaming through an app here. So that’s been helping me stay connected with life back home,” Ahrendsen says.

As an adventurer and outdoorsman, Jon Ahrendsen is effusive about the beauty of the landscape of Antarctica. He also has a chance to see seals and other animals not found in his home community of Clarion, Iowa.

‘There’s a lot of common colds’

The caseload is often routine, as all research station residents must undergo a rigorous health screening process before arrival. Respiratory illnesses, strains and sprains, and minor injuries account for the bulk of patients’ complaints.

“This strikes me as very similar to any urgent care or primary care clinic experience that I’ve had in the United States,” says Reeves. “There’s a lot of common colds, for example. There are not too many unique cases other than perhaps a little bit of cold exposure. But honestly, I grew up in Minnesota and trained in Iowa; I’ve seen farmers with frostbite in Iowa.”

“There’s a big focus on safety here in all departments,” says Ahrendsen, who serves as lead physician for the clinic.

“This year, there are three folks from my residency program who are coming down each for about one month at a time,” Reeves says. “We round out the clinical support team with the other deployed UTMB medical staff, a physician assistant, a flight nurse, a nurse manager, and a rotating three-person team from the U.S. Air Force.”

In 1961, Soviet physician Leonid Rogozov gained notoriety when he performed an emergency appendectomy on himself while a member of an Antarctic expedition. The story might come to mind for medical history buffs upon hearing the word “Antarctica,” but nothing like that is likely to happen on the ice these days, Ahrendsen says.

“Now we can pretty effectively treat that with antibiotics,” he says. “We are not set up to do major surgery here, but we do have the capabilities to take X-rays and labs. We have a full trauma bay that has ventilators, defibrillators, and IV pumps. So, we can deliver critical care here, but if people need major surgery or major interventions, such as caring for a heart attack, they would need to be evacuated to Christchurch.”

“If needed, we could run an intensive care unit for several days,” Reeves says. “We have an inpatient ward with four beds, so we could take care of folks who were critically ill up to standard of care. But the goal would be to prevent any major medical events from happening in the first place.”

“There have even been cases where our station has provided emergency medical care to critically ill passengers on cruise ships,” Ahrendsen says.

Being on ‘another planet’ and coming back home

The experience has taught Reeves the importance of self-reliance and making the most of the resources available.

“It’s been really unique to be in a role in which you don’t have an electronic medical record at your fingertips, and where you can’t just pick up the phone and speak to 20 different specialists,” he says. “You really have to take ownership and be able to figure out what are we going to do with the patient. ‘What resources do I have here? Maybe I don’t have this exact medication, but I can use this other one.’ It’s exposed me to things in medicine that I’ve never seen before.”

When Reeves wasn’t in the clinic, he seized opportunities to explore Antarctica, including accompanying science divers from the research station on an expedition to the sea ice.

“Driving a little bit away from the station, it can feel like you’re on another planet,” he says. “Sometimes being in the station you don’t really quite realize, but we are in fact in an extremely remote environment and, really, I don’t think I’ve ever been anywhere on Earth that looks like this. It’s very special to be a part of this community, supporting all of the science that gets done down here.”

During his time in Antarctica, Isaiah Reeves was able to accompany science divers from the research station on an expedition to the sea ice.

As an adventurer and outdoorsman, Ahrendsen is effusive about the beauty of the landscape. But he’s also looking forward to coming home.

“I have a wife, three adult children, and seven grandkids back in Iowa,” he says. “I am tolerating missing them for now, but I would have to think carefully about missing them for another six months.”