University of Iowa efforts to support pregnant women with substance use disorders are helping to deliver vital health care, provide treatment resources, and keep families together.

Story: Sara Epstein Moninger

Photography: Liz Martin and Joey Loboda

Published: Dec. 13, 2024

The top photo...

Amanda Eleazer overcame substance use disorder while she was pregnant thanks to the compassionate perinatal care she received at University of Iowa Health Care. She now pays it forward by working with patients at UI Health Care Addiction and Recovery Collaborative.

Amanda Eleazer remembers when she started using drugs. It was 2014, and she was a 25-year-old mother of four living in Tennessee. Her husband was a patient at a local pain clinic, which she now realizes was a “pill mill,” a facility that illegally prescribes opioid painkillers such as oxycodone.

He would offer to share his pills with her, and at first Eleazer declined. But one day, she accepted — and everything changed.

“Taking even a tiny piece of the pill would give me this amazing feeling, like a burst of pure happiness and energy,” she says. “It quickly took over my whole life. Within six months, we were selling vehicles and borrowing thousands of dollars from my mother-in-law. When the government became strict on pills, we started buying them from people we didn’t know and spending $40 a pill. Then someone we knew suggested we do heroin because it was cheaper.”

They did, but when Eleazer tried to stop, she would get sick and then start using again to feel better, and the cycle would continue. Hoping for a fresh start, the family moved to Burlington, Iowa, but it wasn’t long before the couple succumbed to their addiction, ultimately leading to Eleazer’s mother-in-law taking custody of their kids in Tennessee. In 2017, her husband was admitted to University of Iowa Health Care for endocarditis caused by IV drug use — and Eleazer learned she was pregnant. This time, she started a treatment program, but when her newborn son was 3 months old, he went down for a nap and never woke up.

The death, attributed to sudden infant death syndrome, plunged Eleazer into an unimaginable darkness.

“I gave up on life completely and for so many different reasons. I had no plans on getting sober,” she says. “When I found out I was pregnant again in 2019, I didn’t know what I was going to do.”

That’s when Eleazer contacted the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition, a nonprofit organization that advocates for people who use drugs. Staff put her in touch with a nurse-midwife at UI Health Care who encouraged her to seek prenatal care at the Iowa City hospital — and everything changed. This time, the change was for the better.

“[Dr. Alison Lynch] values people with lived experience. She values what we think and what we say, and it’s not just me — it’s all of her patients. It’s pretty amazing.”

Offering care with compassion

Despite an initial hospital visit that left Eleazer feeling ashamed that she hadn’t sought help for her addiction earlier, she received almost daily text messages from the nurse-midwife, who checked in to see how she was doing and implored her to return to UI Health Care for follow-up appointments. Eleazer ultimately obliged and delivered her son in Iowa City.

“Honestly, I came to the hospital with the idea that I would leave by myself and that my son would have a better life somewhere else. But the second he was born, my whole life changed, and I’ve been sober ever since. Now he is 4 years old and thriving. He’s smart and funny and very sensitive,” she says. “If I hadn’t connected with Meagan, I don’t know that my life would look this way. I don’t think my son’s name would be Luca, and I probably wouldn’t know where he was.”

Although that nurse-midwife, Meagan Thompson, now works in Minnesota, the maternal substance use disorder clinic she helped start at UI Health Care continues to offer nonjudgmental perinatal care to help people like Eleazer reduce or stop substance use. Staff members at the Supporting Opportunities, Achievements, and Recovery (SOAR) Clinic see more than 40 patients a year and provide postpartum care for up to a year.

In Eleazer’s case, she was referred to Heart of Iowa, a residential substance use disorder treatment facility in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. There, she received the support she needed to meet her recovery goals and bond with her infant.

Alison Lynch, a clinical professor of psychiatry and family medicine who provided care for Eleazer, is on the SOAR Clinic team, and in 2023 she hired Eleazer to work as a recovery coach offering support, guidance, and resources to patients with substance use disorders. The way health care staff interact with patients who have substance use disorders, Eleazer says, can have a huge impact.

Did you know?

University of Iowa Health Care offers substance use support and treatment during pregnancy. Without judgment, the Supporting Opportunities, Achievements, and Recovery (SOAR) Clinic supports pregnant women in cutting down or stopping using substances during pregnancy. Patients can get both comprehensive prenatal care and substance use treatment while pregnant.

As a recovery coach, Eleazer aims to pay it forward. She draws from her experience to help UI patients; she also travels the country to share her story and chip away at the stigma associated with drug use — that people who use are simply looking for a good time or that they lack the willpower to change. Encountering providers who hold these negative beliefs, she explains, often prevents people who are pregnant from getting the prenatal care they and their babies need.

“I never could have expected the opportunities this job has granted me,” Eleazer says. “Dr. Lynch opened those doors, because she values people with lived experience. She values what we think and what we say, and it’s not just me — it’s all of her patients. It’s pretty amazing.”

“I try to get beyond the misinformation that substance use is about choices or that it’s hopeless, and instead emphasize that treatment is about health care.”

Preparing providers to treat addiction

Lynch, a native Iowan, turned to medicine after teaching math and science for three years in an overcrowded and underfunded school in New York City. She spent more time managing large groups than on teaching students — and she saw firsthand how social dynamics affected student health. A school health clinic piqued her interest, and she decided that a medical degree would better position her to help people one-on-one.

After graduating from the UI Carver College of Medicine in 1998 and completing a residency in family medicine and psychiatry, Lynch joined the UI faculty and quickly found that many of her patients with mental health disorders also had an addiction, whether to alcohol, nicotine, or something else. But she didn’t feel well prepared to treat them.

“In medical school, we learned how to manage somebody in acute alcohol withdrawal, but we didn’t learn how to help somebody not return to drinking when they left the hospital,” she says. “Health care has a lot to offer to people with substance use disorders. Opioid use, for example, is a very treatable condition.”

In 2018, Lynch received a grant to expand access to medications to treat opioid use disorder, which included teaching students, residents, faculty, and health care providers across eastern Iowa about opioid use disorder and the medications to treat it.

“I try to get beyond the misinformation that substance use is about choices or that it’s hopeless, and instead emphasize that treatment is about health care,” she says. “What’s even more powerful is that people do really well with treatment, so we have the satisfaction of providing health care and helping our patients heal, which is why most of us go into this profession.”

Lynch, who started an addiction medicine fellowship at Iowa, also shares her expertise more broadly. She is president-elect of the Iowa Medical Society, the largest professional association for Iowa physicians, and communicates with state legislators on the effect of policies.

“We need to embrace addiction as a health care problem,” she says. “The impact of having a family member removed from your family or being in a family where there’s substance use that doesn’t get addressed is lifelong.”

By sharing their personal experiences, Eleazer and the three other recovery coaches on the hospital staff play important roles in the treatment process, as they model how well people can do with help, Lynch says. “We rely on them to be ambassadors for our program and to create a sense of trust with our patients.”

Despite ominous statistics — in Iowa, there was a 160% increase in opioid-related deaths among those under the age of 25 between 2019 and 2022 — Lynch says she feels hopeful for the future.

“The good news is that there are more conversations about addiction happening now,” she says. “There has been an increase in recognizing the human components of substance use and the impact of our punitive, judgmental, and stigmatizing ways of addressing or not addressing substance use. Although we still need more emphasis on keeping families together and on treatment that is as compassionate and holistic as possible, I do feel like the needle is moving.”

“I want to make sure that we’re asking the right questions and not making assumptions that are not appropriate to make. Researchers and health care providers are not immune from stigma and bias.”

Changing the narrative

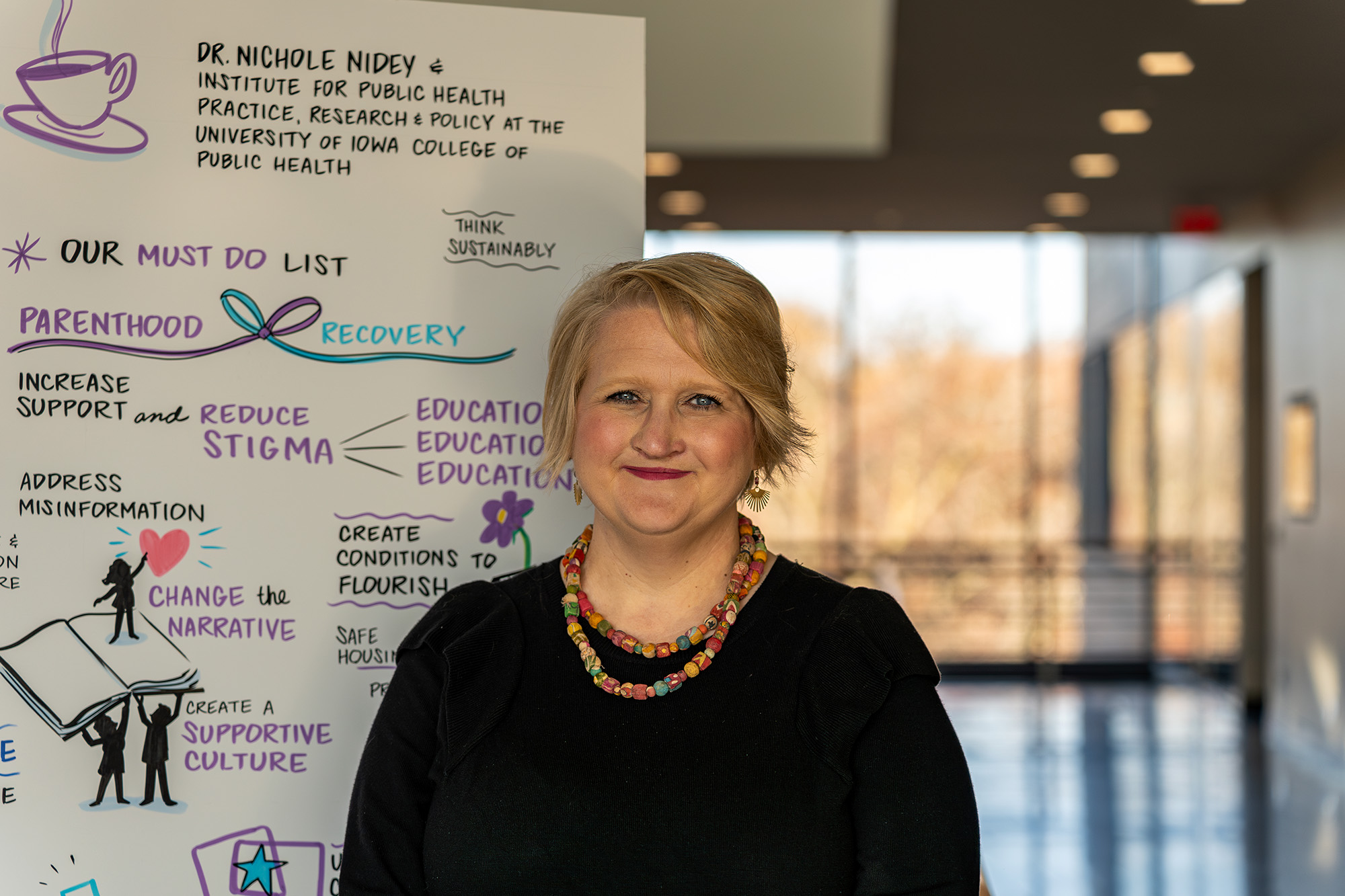

Dedicated to moving that needle is a maternal-child health epidemiologist in the UI College of Public Health. Nichole Nidey, who joined the UI faculty in 2023, has made it her life’s work to advocate for pregnant women and mothers with substance use disorders — by involving in her research those, like Eleazer, with lived experience.

During her graduate studies at Iowa, Nidey was struck by how people with substance use disorders were presented in the research studies she was reading, and she switched her focus from maternal mental health to substance use.

“I’ve known and loved people who use drugs, and I did not see them represented on those pages. I saw a deficit in the narrative and a lot of assumptions that did not check out with what I knew personally,” says Nidey, who earned from Iowa a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and master’s and doctoral degrees in epidemiology. “While working on my dissertation, I tried to see if there was any evidence of people with lived experience of drug use being meaningfully involved in the research process, and I couldn’t find anything. So, when I started my postdoctoral fellowship at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, I wrote my first grant, and that was EMPOWER.”

The EMPOWER Project, Nidey says, aims to involve people with lived experience in the development of training curriculums for providers who see perinatal patients with substance use. She recruited 20 women across seven states to join and inform her work, which she continues today at Iowa.

“I want to make sure that we’re asking the right questions and not making assumptions that are not appropriate to make,” she says. “Researchers and health care providers are not immune from stigma and bias.”

In addition to engaging with those mothers, Nidey has been gathering perspectives from health care professionals, researchers, policymakers, and community members. In September 2024, she invited several dozen people to the UI College of Public Health to brainstorm and develop strategies for improving care for Iowans with substance use disorder, with special attention to methamphetamine use. It was a casual, World Café–style event in which participants met in small groups to discuss related topics.

“That event created connections that people hadn’t had before — many in that room have significant impacts on people who use drugs during pregnancy but have never been with each other in the same room,” she says. “I’m hoping those connections will help move forward some issues that we had discussed.”

Next up, Nidey says, is employing some of the tactics discussed. “If we have a better understanding of addiction and the reasons why people use drugs and why it’s really hard to stop using drugs, I think that can inform better policies in the state.”

It’s an issue all Americans should care about, Nidey adds.

“Overdose from opioids and stimulants is among the leading causes of maternal mortality in the United States — that’s not just losing a mom, it’s losing a sibling or a daughter,” she says. “Many of the bad outcomes we see with these families are not necessarily due to the drug but rather to bad policy and the stigma associated with drug use.”

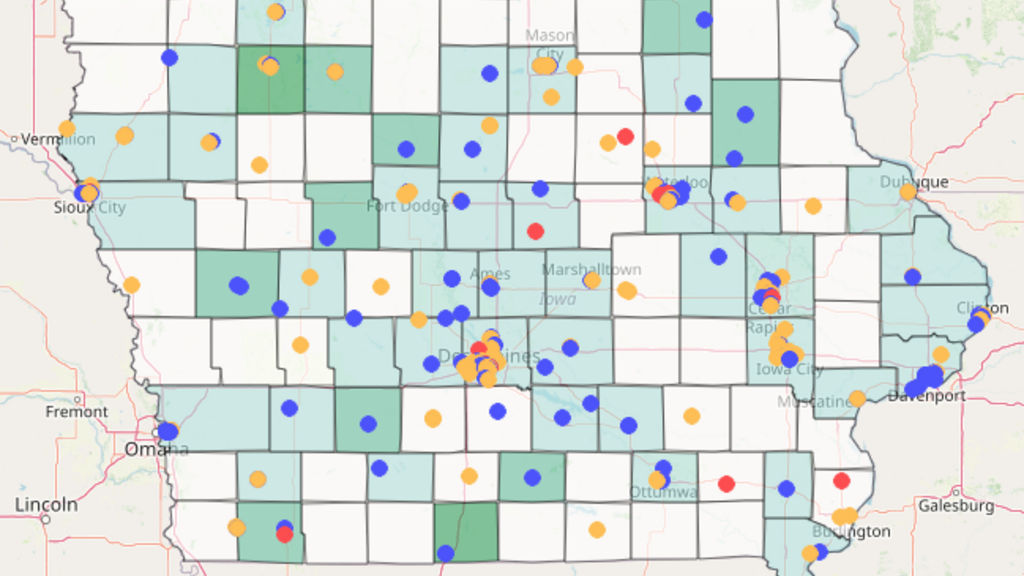

A new interactive map to find treatment options

Nichole Nidey’s research team developed a new online tool that maps substance treatment centers available for pregnant women in Iowa.

From stigma to support

In a guest column for The Des Moines Register, Nichole Nidey writes that Iowa can lead the way by investing in comprehensive, statewide education campaigns that focus on the realities of substance use disorder, highlighting that it is a health issue, not a moral failing.

As a recovery coach, Amanda Eleazer aims to pay it forward. She draws from her experience to help UI patients; she also travels the country to share her story and chip away at the stigma associated with drug use — that people who use are simply looking for a good time or that they lack the willpower to change.

Amanda Eleazer regularly travels to visit her older kids, who now live in Florida. The oldest is a first-year college student. Eleazer’s husband, with whom she had split after the death of their baby, maintained sobriety for over a year before dying in 2019 from an accidental overdose.

Eleazer has been sober for nearly five years — and says she is the happiest she has ever been.

“I never thought that I could get to this point. I think it’s important to know that at the end of the day, no matter how horrible things have been in your life, things can change. But if you automatically count someone out because they use drugs, then you might miss an opportunity to change their life,” says Eleazer, whose 10-year plan includes opening a sober living home in Iowa City for women. “It’s so important to humanize people with addiction. I often wonder how many people didn’t get the chance that I’ve gotten.”

Eleazer credits UI Health Care and its staff for her sustained recovery.

“A lot of hospitals are not like this one. Everybody always says, ‘Well, you did the hard work.’ But there were so many people helping me behind the scenes,” she says. “It never gets old to me that I work here. It’s a special place.”