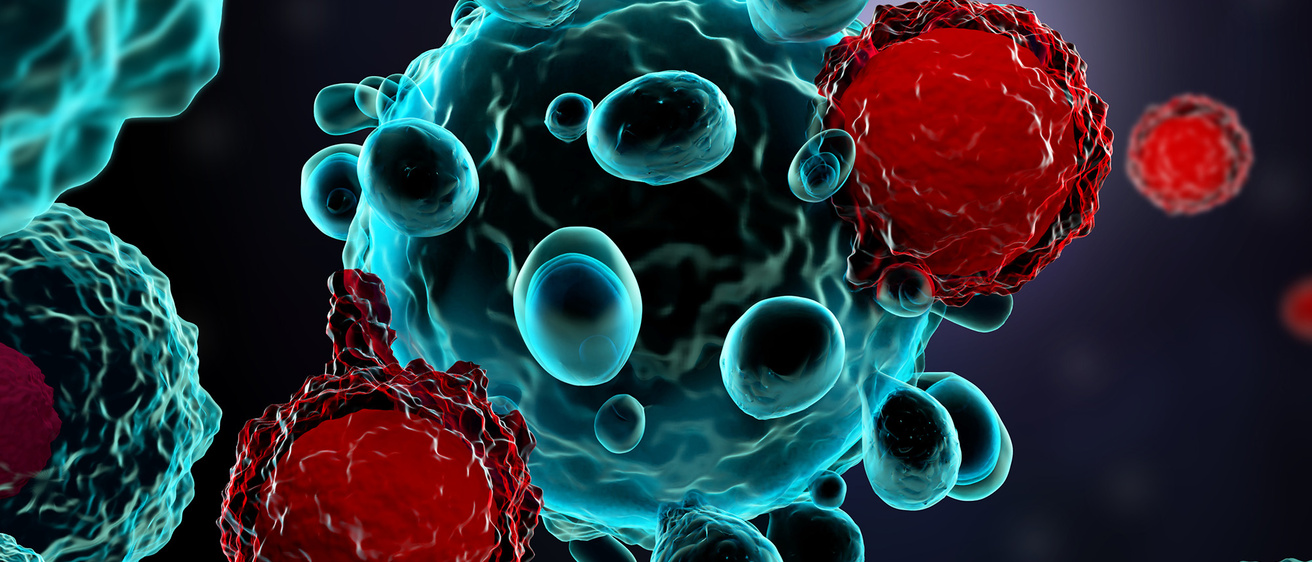

A type of immunotherapy that takes a patient’s own white blood cells and modifies them in the lab to better recognize cancer works remarkably well in the treatment of certain blood cancers. The University of Iowa now is looking to reproduce similar results in other cancers.

Story: Sara Epstein Moninger

Illustration: Meletios Verras

Photography: courtesy of Chris Ferenzi

Published: April 24, 2023

Chris Ferenzi was enjoying a family vacation in Texas in the fall of 2018 when he saw something that gave him pause: a rash developing on his arms.

A year earlier, a similar rash was followed shortly thereafter by the discovery of a lump in his groin, and that had led the Cedar Rapids, Iowa, resident to a diagnosis of a grass allergy—and stage 4 non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The cancer had caused his immune system to react severely to the allergen. He was referred to University of Iowa Health Care, where he received chemotherapy and later was declared in remission.

When he returned from his trip south, Ferenzi, a team lead at General Mills, noticed a strange sensation in his neck while he was stretching at work. He felt around and detected a pea-sized lump. Testing confirmed his fears: The cancer had come back.

That’s when Ferenzi’s doctors at Iowa asked him to consider participating in a clinical trial probing the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy, a type of immunotherapy that uses a patient’s own white blood cells to track down and kill cancer cells. White blood cells called T lymphocytes are extracted from the patient and modified in a lab to add a protein called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), which allows the cells to bind with and destroy cancer cells. The altered cells are multiplied and then reinfused into the patient’s bloodstream. The one-time treatment requires a hospital stay of two to three weeks.

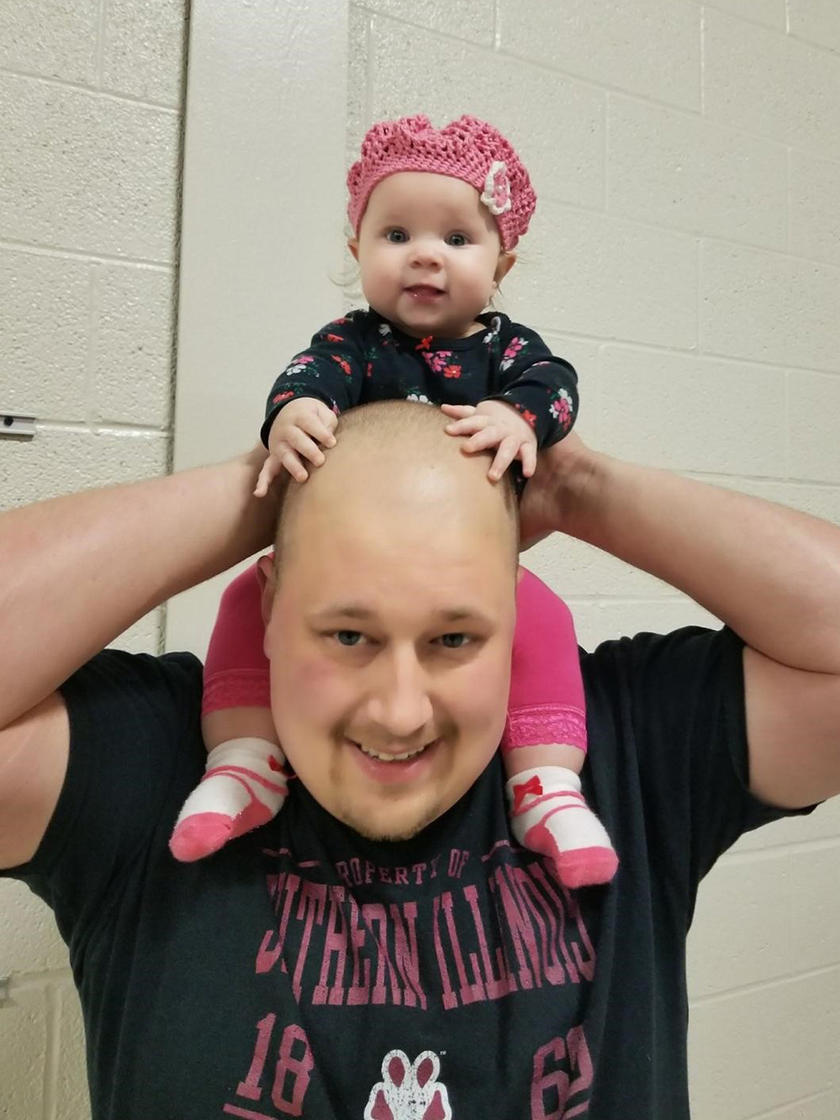

Feeling bolstered by his general good health and age—he was only 33 when first diagnosed—Ferenzi was eager to give the experimental treatment a try. He wanted to give his newborn daughter a chance to know her father.

Chris Ferenzi was eager to give CAR T-cell therapy a try, as he wanted to give his newborn daughter a chance to know her father.

Six years later, Ferenzi is cancer free and feeling good. He returns to the UI hospital for scans every six months. “It was tough,” he says of his three-week hospitalization. “My head really hurt for the first week, then I was fatigued. It took a while to get my fever down. But I’d do it again over chemo any day of the week.”

CAR T-cell therapy at Iowa

Iowa was among the first institutions in the country to study the use of CAR T-cell therapy in certain blood cancers. Clinical trials had shown that 80% of lymphoma patients went into remission and 50% into complete remission.

Umar Farooq, MD, head of Iowa’s CAR T-cell program and clinical associate professor of hematology, oncology, and blood and marrow transplantation, says his clinic is now full of patients who wouldn’t have survived long when he started at Iowa in 2014.

“Most of my patients back then were not going to make it beyond six months,” he says. “The chances of going into remission with any therapy at the time was around 25%, with complete remission at just 7%—so CAR T-cell therapy offers a huge improvement. It feels like a miracle.”

CAR T-cell therapy now is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for lymphomas, multiple myeloma, and some forms of leukemia in patients for whom other treatments have failed. UI Health Care is the only health care provider in the state authorized to give the treatment and is enrolling patients in clinical trials attempting to reproduce the therapy’s effectiveness in solid tumors.

“For the longest time, the most effective treatment for cancer was chemo, chemo, and more chemo — without a really good response,” Farooq says. “Now that we recognize the power of cell therapy, we have seen an exponential increase in the number of clinical trials. The results in leukemia, myeloma, and lymphoma are very good, and we hope to see that same response in solid malignancies.”

How CAR T-cell therapy works

- White blood cells known as T lymphocytes are drawn from a patient and sent to the lab.

- The lab modifies the cells to grow chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) on their surfaces.

- These new CAR T cells are multiplied in the lab.

- After low-dose chemotherapy to ensure the immune system doesn’t reject the new cells, the patient receives an infusion of the modified cells.

- The CAR T cells hunt down and attack cancer cells.

“CAR T-cell therapy is a new tool we have to target cancer cells — and the more ways that we have to target cancer cells, the better.”

Expanding CAR T-cell therapy to solid tumors

UI investigators are now working on new clinical trials studying CAR T-cell therapy in multiple cancers, including kidney cancer, lung cancer, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and breast cancer. They are also looking into whether CAR T-cell therapy can be used earlier in a cancer treatment regimen.

Emily Hill, MD, clinical associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology–gynecologic oncology, has enrolled ovarian cancer patients in CAR T-cell clinical trials. Although ovarian cancer is a relatively rare cancer, the five-year survival rate is less than 50%. Surgery and chemotherapy can be effective, she says, but the duration of remission varies. She is optimistic about CAR T-cell therapy.

“It’s not like trying a slightly different chemotherapy — it’s coming at the cancer from a completely different angle. Given how limited our improvements have been with the more traditional approaches, we must think broader,” Hill says. “There’s no way we can accept the current prognosis for women with ovarian cancer as the end game. We must continue to work to improve the care — screening on the front end but also meaningful improvements in treatment on the back end. We’re not going to make major advances without clinical trials.”

Iowa’s role in advancing cancer medicine

Cancer is among the leading causes of death worldwide, and it is predicted that 6,100 Iowans will die from cancer in 2024, according to the latest Cancer in Iowa report. Experts at the University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center are dedicated to fighting cancer and improving therapies.

With its comprehensive cancer center designation from the National Cancer Institute, Holden is one of 57 institutions across 36 states — and the only one in Iowa — recognized for its leadership, resources, and research in cancer medicine.

Hill says it will take time to understand the full impact, “but as a one-and-done treatment, CAR T-cell therapy could be a game changer. Patients don’t have to keep coming back.”

The future of CAR T-cell therapy

Since the FDA’s approval of CAR T-cell therapy in patients with multiple myeloma in 2021, UI patients have been asking for it. Christopher Strouse, MD, clinical assistant professor of internal medicine–hematology, oncology, and blood and marrow transplantation, says he is happy to discuss the treatment with patients and whether it is appropriate.

“Right now we can’t cure multiple myeloma, but CAR T-cell therapy is a new tool we have to target cancer cells — and the more ways that we have to target cancer cells, the better,” he says. “We’re at the very beginning of combining the tools we have and figuring out the best order in which to use them. I’m very hopeful that Iowa will be part of those advances moving forward. And maybe someday we’ll find a cure.”

Ferenzi, a father of five, is grateful for the extra family time CAR T-cell therapy has given him. He was able to witness his youngest daughter win a Big Wheel race, learn to ride a bike, and lose her baby teeth. He shares Strouse’s optimism about the future of cancer treatment.

“The more research we do, the more we’re going to learn, the more technologies we’ll have, and the more we’ll be able to do for cancer patients,” Ferenzi says. “There’s no doubt in my mind that we’ll soon be able to do this for other cancers.”

The number of clinical trials looking at CAR T-cell therapy is indicative of the promise that cell therapy holds, says Farooq. He is hopeful that it also may help patients with autoimmune disorders and other diseases.

“CAR T-cell therapy holds the potential to harness the power of the immune system,” he says, “but it doesn’t work for everybody, so we need to continue to investigate.”

Why clinical trials matter

Clinical trials at the University of Iowa and other cancer centers are key to making advances in cancer medicine. They help researchers evaluate the latest drug therapies or surgical techniques. By participating, patients have access to some of the most exciting new cancer treatments — ones that may stop their cancer from progressing further. Many trials are available to patients at the University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Dedicated to treating, preventing cancer

University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Care Center is the first and only institution in Iowa authorized to administer CAR T-cell therapy, an innovative immunotherapy that trains the body’s immune system to recognize and kill cancer cells.