A new take on ‘The Great Gatsby’

In 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald published The Great Gatsby, a work that would come to be regarded as a defining novel of the 20th century, finding itself a perennial selection in high school curricula and the subject of numerous stage and film interpretations.

Nearly 100 years later, 19 University of Iowa students are collectively rewriting the 1920s literary classic in the spirit of a 2020s popular genre: fan fiction.

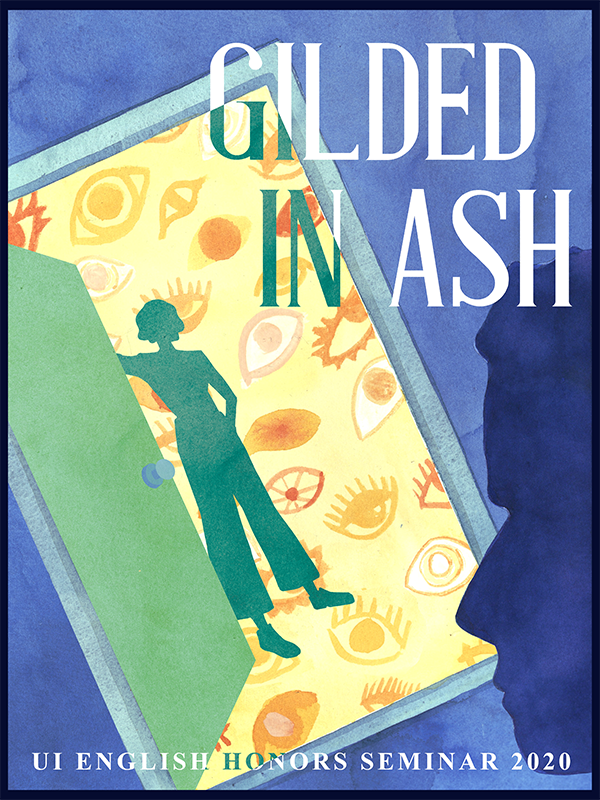

The book’s copyright expires at the end of 2020, meaning anyone will be able to publish the book, write a prequel, or adapt it any way they wish. The Iowa students’ version, Gilded in Ash, will be published online early in the new year by Iowa’s Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio, complete with new cover art.

Associate Professor Harry Stecopoulos says he was brainstorming ways to combine literary criticism and creative writing when it came to him during a run: fan fiction could be the bridge.

“I knew many of our students have engaged in reading and producing fan fiction, so I thought that would be a hook,” Stecopoulos says. “And as it turns out, there is already a great deal of fan fiction for The Great Gatsby, but of the non-academic variety.”

For more than 75 years, the University of Iowa has been a leader in the writing arts. The English and creative writing major enables students to experience the historical, traditional, and innovative aspects of literature as well as the relationship between critical reading, creative writing, and translation. The major provides transferable skills important for a liberal arts major, including the abilities to think deeply and creatively, read complex texts with comprehension, and develop writing and speaking skills at an advanced level.

The class spent several weeks reading the novel in biographical, historical, and literary contexts, as well as some already-published Great Gatsby fan fiction, before writing began. The students—chosen for the honors course based on portfolios—then were divided into nine teams of two or three. Each week, one team would submit an approximately 25-page chapter and the class would read it overnight in time to discuss it during the next two days of class. Decisions based on style, character, plot, and structure were made collectively. The next team would then write the subsequent chapter in line with the existing material and previous decisions. Over the final two weeks, teams reviewed the manuscript for consistency.

“They are changing the novel enormously, but in a historically oriented way,” Stecopoulos says. “They don’t just want to change the novel to talk back to Fitzgerald and correct Gatsby’s 1920s biases. They want to create characters complete in their own right regardless of what Fitzgerald did. They are wrestling with how much they want to revise with an eye to political, aesthetic, and cultural issues, and having passionate debates and arguments. But everyone has been respectful and nice. It’s exciting.”

KayLee Kuehl says class discussions surrounding representation were particularly important to her as one of the few students of color in a majority white class. This included suggestions to make Gatsby—who the class had already decided was a queer woman—African American, and making Jordan Baker an Asian American heiress.

“There was some concern and discussion about what does it mean to stay true to history? Staying true to history does not mean people of color can’t be in positions of power,” says Kuehl, a fourth-year student from DeWitt, Iowa, majoring in English and creative writing and minoring in art and cinematic arts. “Also, what does it mean to provide representation when the majority is not a part of that community? And if so, what does that look like and how do we go about doing this? I believe it was a learning experience for a lot of people. These were discussions that will remain with me as I move forward and grow as a person and a creative.”

Fan fiction has become a welcoming community, particularly for those from minority communities.

“Fan fiction often is a place where fans of literature go when they don’t see themselves represented in popular classic novels,” Stecopoulos says. “They can go back into that novel and change it to find their own identities located there.”

Haley Triem says she can relate, not having seen her identity as a bisexual woman reflected in books or media while growing up.

“It would have been so much easier for me to come out to friends, family, and, most importantly myself, if I had seen just a few gay characters in literature, either in the classroom or outside of the classroom,” says Triem, a fourth-year English and creative writing and art double major from Houston, Texas. “I think what we’re doing here is really important, because we are essentially taking a book—a really great book that has impacted a lot of people—and we’re pointing out the holes in it. And then we’re rewriting those holes to deliberately create reflections of peoples’ identities. As a class, we’re showing how easy it is to create complex characters representative of the LGBTQ+ community, and how those characters don’t necessarily need to be built around their identity; our characters have so many plots and subplots to worry about, and them being LGBTQ+ is just a normal part of their selfhood.”

Kuehl says she was especially excited while helping write her team’s chapter to incorporate a new Black character, Daughter, based on a character from one of her favorite television shows, Boardwalk Empire.

“Reading the book the second time, I really noticed the descriptions of Black people,” Kuehl says. “They sat wrong with me and hurt me. They blatantly stripped people of their humanity. I wanted positive representation, or at the very least representations that were true to me and true to the struggles that my people have gone through.”

Along with helping rewrite The Great Gatsby, Triem is also rethinking the novel’s iconic cover.

“It’s different from other workshop classes where we write 20 pages and that’s as long as it’s going to get. This is something I’m going to gain a lot from when writing my own longer works.”

Haley Triem, a fourth-year English and creative writing and art double major from Houston, Texas, designed the cover for Gilded in Ash. Triem says she received a lot of great feedback from her classmates throughout the process. “Being able to work collaboratively and freely in a way that reflects my two passions—my two majors, art and writing—has been incredibly rewarding and has helped me grow a lot as a creative.”

“When I signed up for this class, I hoped being able to design and illustrate the cover would be a possibility,” Triem says. “I wanted the cover to reference what this project is about as a whole; something more than just a reflection of the original Gatsby. We’ve taken the original and broken it down, distorted it, reconstructed it. We’ve made it our own.”

Triem and the class were inspired by a major element from the original cover and book: the billboard of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg’s eyes staring down over the valley of ashes.

“We wrote a pivotal scene mid-book where our Gatsby, who’s an art forger, comes into a room full of canvases with eyes drawn on them,” Triem says. “I pictured an open doorway with a silhouette and a lot of eyes, with deco elements that reference the time period.

Triem says she has gotten a lot of great feedback from her classmates throughout the process.

“It’s been a really eye-opening experience for me to mentally juxtapose both literary and visual imagery and to allow the two to operate in such an organically collaborative experience,” Triem says. “Additionally, letting go of the reins and stepping back to trust my classmates has been really healthy for me creatively, and I’ve begun to enjoy the at-first unsettling feeling of flying by the seat of my pants from week to week. Being able to work collaboratively and freely in a way that reflects my two passions—my two majors, art and writing—has been incredibly rewarding and has helped me grow a lot as a creative.”

The honors seminar in fiction may be the first of its kind.

“To the best of my knowledge, no one has recreated a major literary work collectively with undergrad creative writing students,” Stecopoulos says. “People have had students read a novel or poem and model it or revise it. But to devote an entire semester to recreating a literary masterwork is something new.”

Triem says this type of class is one of the reasons she left Texas to study writing at Iowa.

“I’ve told people at home and at other schools about this and they are just amazed that this is even a class,” Triem says. “I read fan fiction as a kid, but I never thought I’d be able to write it as a college student for a grade. It blows my mind. It’s been intense and fast-paced, but it’s been one of my favorite classes so far. It’s been such a crazy semester and this class has been just what I’ve needed.”

Stecopoulos says he hopes his students leave the class having learned multiple lessons.

“Creative writing is not normally a collectively oriented discipline,” Stecopoulos says. “It’s usually all about finding your voice and telling your story. But I thought in a time of a pandemic, when everyone sort of feels overly isolated, it might be nice to work on something as a group. Many of my students want to be fiction writers, so I also hope they learn something about the practice of making fiction.”

The collaborative nature of the project resonated with both Kuehl and Triem.

“It’s important, not only for young writers but for young people who are creating as a whole, to work with other people, to listen to different perspectives, and take constructive criticism,” Kuehl says. “What I really appreciate about this class is we have the opportunity to learn from each other and create safe spaces for everyone to express their opinions. We’re really promoting empathy, because that’s what it takes to be able to truly listen, absorb, and take in ideas from someone else. And not only to listen but to put those ideas to pen and paper as we are doing.”

“I think part of the reason it has worked so well is that we have a great classroom culture,” Triem says. “Sometimes classes just click, and we’ve clicked.”

“The artistic world can be competitive. It’s been an exercise in community formation, and that’s so important right now. It’s truly been a bright spot for them and for me in an otherwise dismal year.”

Triem also says working on a long-term project like The Great Gatsby will help her reach her goal of writing children’s books.

“We had an overarching plot that we were always thinking of, along with subplots of each chapter,” Triem says. “It’s different from other workshop classes where we write 20 pages and that’s as long as it’s going to get. This is something I’m going to gain a lot from when writing my own longer works.”

Kuehl says improving her writing and collaboration skills aren’t the only things she’ll take away from the class.

“What I really will bring forward with me is confidence in myself as a writer, as an individual, and as a BIPOC-identifying person to confidently vocalize when I’m met with moments or questions that have to do with accurate or appropriate representation, or having to do with accurate or appropriate discussions involving my identity and my people and my community,” Kuehl says.

Stecopoulos says when he was developing the class, he wasn’t sure how it would all work out. But he says he considers it a success.

“One of the greatest things about this class was working as a 19-person unit without yelling at each other or getting spiteful or nasty,” Stecopoulos says. “The artistic world can be competitive. It’s been an exercise in community formation, and that’s so important right now. It’s truly been a bright spot for them and for me in an otherwise dismal year.”