After taking one class about disease outbreaks, University of Iowa student Justin Krogh switched his career interests to public health. Now, the Sergeant Bluff, Iowa, native wants to pursue a doctorate in epidemiology and emphasize prevention efforts.

Story: Richard C. Lewis

Photography: Tim Schoon

Published: Dec. 7, 2022

One class at the University of Iowa really can change your life.

Just ask Justin Krogh, who will graduate this December from Iowa with a Bachelor of Science in public health and a minor in global health studies. Krogh entered Iowa intent on studying medicine, with an eye toward becoming a doctor and making a living by treating people.

But his academic plans shifted when, in the fall of his freshman year, Krogh enrolled in Finding Patient Zero, a class offered by the College of Public Health. Krogh somewhat sheepishly admits he signed up in part because the course meshed well with his class schedule.

But he soon realized the class was more than a convenient addition to his academic to-do list. He enjoyed how Matthew Nonnenmann, associate professor in occupational and environmental health, unspooled the vast, historical array of diseases, outbreaks, and afflictions that have affected humankind for ages. It was like being dropped into a public health diorama, learning about how diseases materialize, and how their spread can be stymied.

“That class helped me discover the idea that medicine doesn‘t always have to be the first option,” Krogh says. “There is this whole idea of prevention, a horizontal measure to help society instead of treating things as they arise. Let’s work on figuring out the problem that‘s causing it instead of just always treating it.”

Krogh was accustomed to the treatment proposition. He grew up in Sergeant Bluff, Iowa, on a fifth-generation farm. Just about every day, Krogh returned from school to help attend to the family’s 300-head cattle livestock operation. His duties included daily feeding, vaccinating the herd, assisting with calves’ births, and getting the cattle out to pasture in the spring.

Justin Krogh

Hometown: Sergeant Bluff, Iowa

Degree: BS, public health (minor in global health studies)

Future plans: Pursue a doctorate in epidemiology

“I think some of the biggest things the farm taught me was a sense of discipline, and the motivation to want to get things done in a timely fashion,” he says.

The daily regimen of tending to cattle, along with some high school classes in biology and health, explains in some measure why Krogh was interested in medicine. He chose Iowa largely for that reason, and matriculated as a pre-medicine and human physiology major.

“That (Finding Patient Zero) class helped me discover the idea that medicine doesn’t always have to be the first option. There is this whole idea of prevention, a horizontal measure to help society instead of treating things as they arise. Let’s work on figuring out the problem that’s causing it instead of just always treating it.”

After switching his interest to public health, Krogh made good on another goal: to get involved in research. So, the summer before his sophomore year, Krogh got on a jobs platform called Handshake, which every UI student has access to, and started scrolling through the myriad entries. One caught his eye: a research assistant position helping perform clinical trials in the pediatric pulmonary division at UI Health Care Medical Center.

“What interested me the most about it is I wasn’t going to be sitting in a lab doing benchtop research,” Krogh says. “I was going to be working in a hospital setting and interacting with subjects and patients.”

Krogh learned specifically who he’d be interacting with when he showed up for an interview.

“They asked me, ‘What do you know about cystic fibrosis?’” Krogh recalls. “And I said, ‘I’m going to be completely honest with you. I don’t know anything.’ But I’m willing to learn—that’s kind of how I grew up. I mean, you just dig in and figure it out.”

Krogh started out by visiting with children and gauging the effectiveness of a medication designed to reduce mucus buildup in the lungs and other areas of the body, the chief symptom of cystic fibrosis. During those visits, Krogh would prepare and take lung mucus samples, and speak with the children and their parents.

It was humble work, but gratifying.

“The best part of it is I got to see the results of these research trials,” Krogh says. “Even as a research assistant, my simple role was to help them to become healthier and to live a better life. It was inspiring.”

He also learned he was interested in the public-health dimensions to clinical trials, such as their design, safety, and ethics.

Iowa’s world-class public health education

The UI College of Public Health offers more than classroom learning. Our undergraduate students get hands-on experience here in Iowa City and learning opportunities around the globe.

At Iowa, we prepare our students for rewarding careers in public health practice or further academic study in public health, medicine, law, dentistry, or other graduate and professional programs.

Last summer, Krogh made good on that interest when he began an independent project called “Building Trust in Cystic Fibrosis Research.” His project, part of the College of Public Health’s experiential learning requirement for graduation, centers around easing the barriers that can exist between patients, as research subjects, and the researchers, who lead Phase I clinical trials, when promising treatments are tested for the first time in humans.

Part of that challenge is the lack of information or knowledge that patients have about a given clinical trial, Krogh says, which can make them feel uneasy about participating. That’s where the researchers can help alleviate that apprehension by clearly explaining the goals—as well as any risks—with the clinical trials for which they seek participants.

Krogh begins the conversation by asking a simple question, such as whether they would want to be involved in a clinical trial. As an icebreaker of sorts, he uses a set of pictures, such as seeds growing into plants, a bright blue sky with balloons, a rocket ship, or a traffic jam on a freeway. Each picture indicates how the patient is feeling, from wholeheartedly excited to participate in a clinical trial to heavy reluctance.

Depending on the response, Krogh uses pictures to ask more questions to ultimately help establish trust between himself and the patient.

“It just helps to build a conversation with a person whom you may not know well, and you want to demonstrate that you have a vested interest in their health in order for them to want to buy in,” he says. “We want them to know it’s not just what we want to do, but they have a voice in this as well.”

Join the Hawkeye family!

Iowa will prepare you, challenge you, and change you. You will change the world. We accept applications year-round.

Mary Teresi, a clinical pharmacist and director of pediatric pulmonary and epilepsy clinical trials in the Carver College of Medicine, hired Krogh for his first research opportunity. She says Krogh has progressed from learning the filing system and reading hundreds of pages of protocols governing different clinical trials to becoming a primary research assistant who is teaching other undergraduates how to successfully carry out and document a visit.

“If you can teach somebody what you’re doing, that shows you’ve really got it,” Teresi says.

Most recently, Teresi has been guiding Krogh on his cystic fibrosis independent project. She says Krogh has an engaging, outgoing personality and easily establishes rapport with patients.

“He’s comfortable in his own skin, so to speak,” Teresi says.

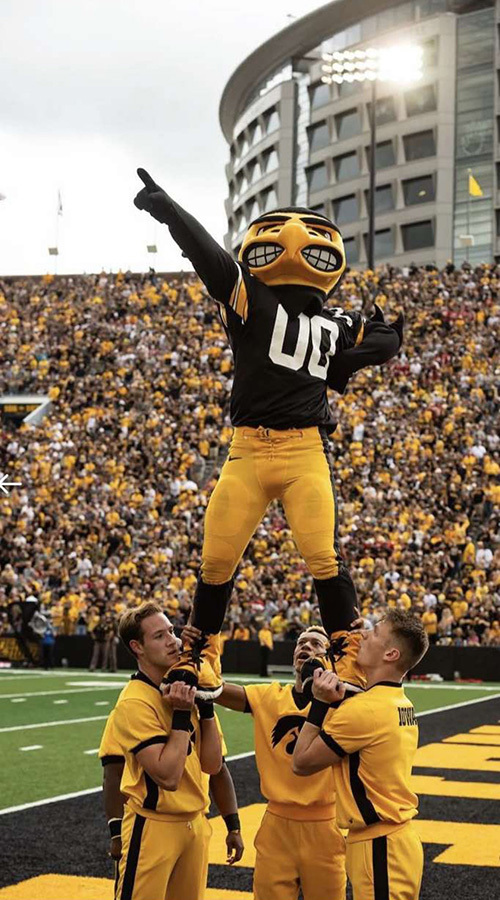

Krogh also is comfortable in another guise, as Iowa’s beloved Herky mascot. Teresi says Krogh pulled some strings to get himself, as Herky, to visit the pediatric unit at UI Health Care Medical Center.

“He took the extra steps to make it happen, and just to see the reaction from the kids when they saw Herky, they just bombarded him,” Teresi says.

Krogh says he enjoys making people smile, whether it’s parading as Herky in front of a sellout crowd at Kinnick Stadium or in one-on-one visits with patients.

Justin Krogh says he enjoys making people smile, whether it’s parading as Herky in front of a sellout crowd at Kinnick Stadium or in one-on-one visits with patients.

“Sometimes all people need is a little laughter to make their day better,” he says.

After graduation, Krogh plans to study epidemiology, in hopes of earning a doctorate.

“I really like the idea of being a professor, combining teaching with scientific research to improve the future of the workforce in public health,” he says.