For 40 years, the Iowa Marrow Donor Program has led the way helping those in need get the lifesaving transplants they require. And it wouldn’t be possible without the kindness and selflessness of Iowans, especially the young adults on campuses across the state.

Story: Emily Nelson

Published: June 14, 2021

In May 2019, the Linnekin family learned that chemotherapy was not working against their 7-year-old daughter’s acute myeloid leukemia. Alivia would need a bone marrow transplant.

“It’s terrifying to hear your child needs this in order to survive and you’re depending on the kindness of somebody who knows nothing about you,” says Denise Linnekin, Alivia’s mother.

The Dallas, Georgia, family found that kindness in an Iowan.

Michaela Heys, a medical student at Des Moines University who grew up in New Sharon, Iowa, had joined the national Be the Match marrow registry only a few months earlier. She donated bone marrow for Alivia in August 2019 at University of Iowa Health Care Medical Center.

“I still get emotional talking about it now,” Heys says. “It’s incredible to know that you can do so little and save someone’s life.”

At 40, the Iowa Marrow Donor Program, based at University of Iowa Health Care Medical Center, is one of the oldest such programs in the country. UI Health Care Medical Center performed its first marrow transplant from an unrelated donor in 1981.

“We really were pioneers in exploring that therapy,” says Colleen Reardon, manager of the Iowa Marrow Donor Program. “And when the national registry program—now known as Be the Match—started in 1987, it looked to us as a template.”

Seventy percent of people who need a bone marrow transplant do not have a match within their family, making the registry critical for finding donors.

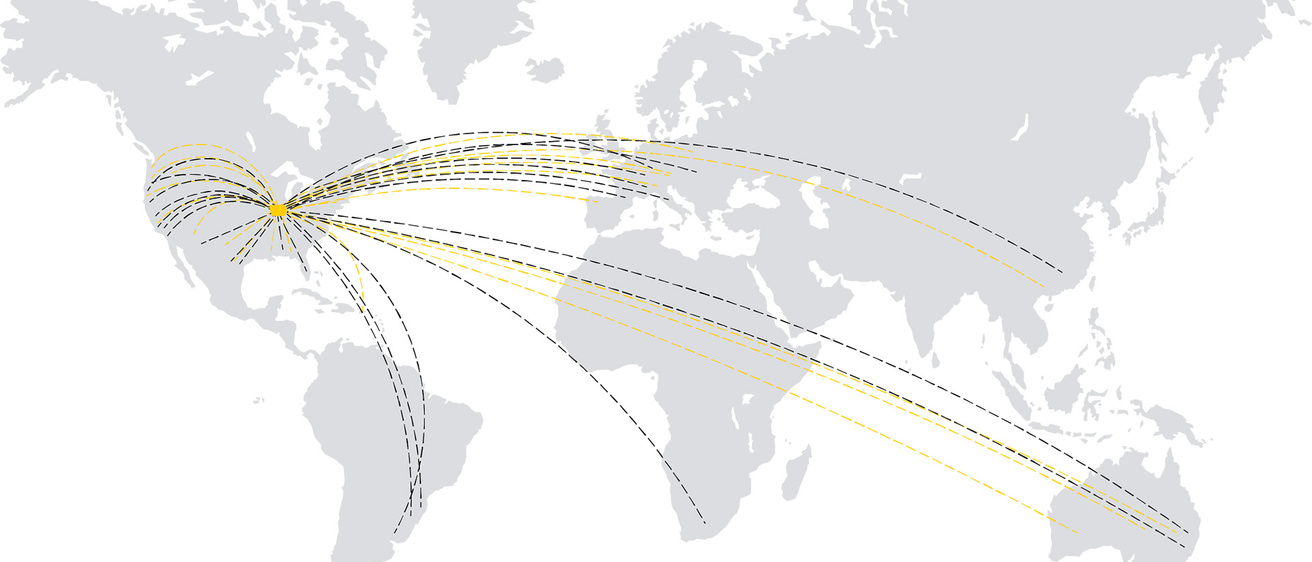

And over the past 40 years, more than 900 Iowans have stepped up to save the lives of strangers across the world.

The Iowa Marrow Donor Program has consistently ranked as the No. 1 donor center in the country. Reardon says the ranking is based on several factors, including how many potential donors, when called, actually go forward with the donation.

Alivia Linnekin (left) received a bone marrow transplant in 2019. A year after the transplant, Alivia met the donor, Michaela Heys, a New Sharon, Iowa, native who matched with Alivia just months after joining the donor registry. “Alivia felt an immediate connection with Michaela,” says Denise Linnekin, Alivia’s mother. “They have a special relationship.” (Photo courtesy of the Linnekin family.)

“The national average is about 50%, but in Iowa it’s close to 85%,” Reardon says. “Iowans come through. We help our neighbors, no matter where they are.”

That includes during a global pandemic. Reardon says the center saw a record number of donations during 2020. Part of that was due to programs in neighboring states shutting down for a time and people traveling to Iowa to donate instead. But Iowans showed up as well.

“When many people across the country were hesitant to go to a hospital or really anywhere in public, Iowans did not hesitate to do what they could to help someone they didn’t know. It was amazing.”

Much of the Iowa program’s success is due to the state’s college students, who spearhead registration drives and sign up themselves on Be the Match, which focuses on recruiting members ages 18 to 44.

“‘Iowa Nice’ is so real,” says Giselle Coreas, president of the student group Be the Match on Campus–UI. “My peers at the University of Iowa really want to help. They want to educate themselves and make that commitment. They’re engaged, and they understand the impact they can make.”

After 40 years, the Iowa Marrow Donor Program has seen many changes, but it continues to evolve in order to better serve the patients who desperately need it, such as increasing the diversity of the donor pool to improve the odds that every patient who needs a match can find one.

Program evolves over 40 years

While Iowans’ selflessness hasn’t changed over the years, a lot else in bone marrow donation has.

Logistics, for one. When the program started, donors would travel to UI Hospitals & Clinics, whether they lived in Des Moines, Iowa, or London, England.

“Donors would actually sit in the room with the patient while the patient got their cells,” Reardon says. “Now, of course, that’s confidential. And our donors can donate closer to where they live and the cells are carried by couriers to the transplant center.”

Matches used to be determined by mixing a bit of patient blood with donor blood to analyze the reaction. Potential Iowa donors would get their blood drawn at a local hospital or clinic in the morning, and Civil Air Patrol or the Iowa State Patrol would rush the samples to Iowa City, no matter the weather.

“New technology means we don’t need to do that anymore, but those teams led to the successes that we have today,” Reardon says.

Today, a simple cheek swab can determine a potential match, and donors can do the swab at a registry event or have a kit mailed to them at home.

Another major change arrived in the late 1990s regarding where the healthy blood-forming cells used in a transplant came from. The same blood-forming cells found in bone marrow are also found in a person’s circulating blood. Harvesting peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) is easier and less invasive for a donor. PBSC donation is now far more common than bone marrow harvesting, with 80% of donors now being asked to give PBSCs.

Two types of donations

The same blood-forming cells that are found in bone marrow are also found in the circulating (peripheral) blood.

Eighty percent of donors give peripheral blood stem cells.

Peripheral blood cell (PBSC) donation: Donors will be given injections of a drug to increase the number of blood-forming cells in their bloodstream for five days leading up to donation. PBSC donation involves removing a donor’s blood through a needle in one arm, passing it through a machine that separates out the cells used in transplants, and returning the remaining blood through the other arm. The donation process may take up to eight hours.

Bone marrow donation: During this outpatient surgical procedure, liquid marrow is withdrawn from the back of the donor’s pelvic bones using needles. Anesthesia is always used for this procedure, so donors feel no pain during marrow donation. Most donors feel some pain in their lower back for a few days after. Most donors will be in the hospital one day, but some may need to stay overnight for observation.

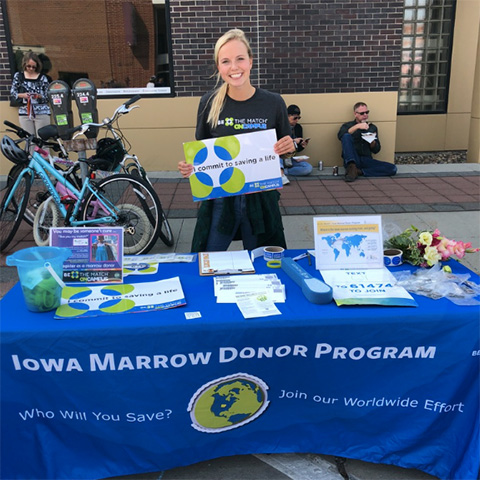

Be the Match student organizations focus on recruiting their peers by holding large donor-registry events and pop-up stands at residence halls or academic buildings, where they can do cheek swabs on site. They also work directly with Dance Marathon and other student groups. (Photo courtesy of Be the Match–UI.)

Students lead the way

“Did you know you can cure cancer?”

This is the opening line of Maddie Huinker’s pitch to fellow students during drives to recruit potential bone marrow and PBSC donors on the Iowa State University (ISU) campus.

“They usually ask me what I’m talking about, and I tell them that these transplants are cures for more than 80 different blood cancers and diseases,” says Huinker, who graduated from ISU in May 2021. “Right now, there are thousands of patients who are waiting for their match, and that person is out there somewhere in the world. I tell them, ‘You may be that match.’”

Huinker has seen firsthand the impact that bone marrow donation can have on a patient and their loved ones. Her childhood friend was diagnosed with T-cell lymphoma when they were both in high school, and while he died from the disease, Huinker says a bone marrow transplant gave him precious time.

The Iowa City, Iowa, native signed up on the Be the Match registry the day she turned 18, has served as president of ISU’s Be the Match student chapter, and is currently a marketing intern for the Iowa Marrow Donor Program.

Students on Iowa campuses have been involved in donor recruitment efforts for decades.

On July 8, 1992, 275 people turned up at the Iowa Memorial Union for a bone marrow donor drive for UI student Wen-Ling Wen, a graduate student diagnosed with leukemia. The response was so strong that a second drive was scheduled for the next day.

While a match for Wen was not found that day, it marked the beginning of a social movement on campus. Now an official student organization known as Be the Match on Campus–UI, Iowa students have been registering as donors and organizing marrow donor drives ever since—as have college students across the state.

“As a society, we’ve become more polarized, but here’s something that a student can do that has a direct impact on the life of a family — not just the patient, but everybody who knows and loves that patient,” says Reardon, who started recruiting on Iowa college campuses in the 1980s. “They know they’re putting something good out there in the world, and that they are potentially in a position to be the one person who can make a difference in someone’s life.”

Maddie Huinker, an Iowa City, Iowa, native, signed up on the Be the Match registry the day she turned 18, has served as president of ISU’s Be the Match student chapter, and is currently a marketing intern for the Iowa Marrow Donor Program. Huinker, who will start grad school at Iowa next fall to pursue a Master of Health Administration degree, uses her skills to create video, graphics, fliers, and social media content. “I just really am looking for any opportunity to recruit that I can,” she says. (Photo courtesy of Maddie Huinker.)

Coreas learned about the Be the Match on Campus–UI student group from an email. The group’s mission really hit home with the then-first-year student from West Liberty, Iowa, as her father had just been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer.

“Along with just wanting to get involved, I also didn’t want anyone else to have to be in the same footsteps we were,” says Coreas. “I’ve continued with it and grown and met so many amazing people.”

Be the Match student organizations focus on recruiting their peers by holding large donor-registry events and pop-up stands at residence halls or academic buildings, where they can do cheek swabs on site. They also work directly with Dance Marathon and other student groups.

COVID-19 has put in-person events on hold, but the groups’ members continue to find ways to reach out to their fellow students and help facilitate mailing cheek swabs to potential donors’ homes.

Huinker, who majored in communication studies and environmental studies with minors in business and global health, will start grad school at Iowa next fall to pursue a Master of Health Administration degree. As the marketing intern for the Iowa Marrow Donor Program, she is using her skills to create video, graphics, fliers, and social media content.

“I just really am looking for any opportunity to recruit that I can,” Huinker says.

Coreas and Huinker say their biggest challenge is making students aware of bone marrow and PBSC donation. They say once they explain how it works and what it could mean to a patient with a blood disease, most students are willing and excited to join the registry.

“Iowans have a great sense of community, and that’s a state trait we can be proud of,” Huinker says. “Whether you’re a Hawkeye or a Cyclone, people care about one another and recognize that there is a need.”

Huinker says she hopes to one day get the call to donate. But even if she doesn’t, she knows she will have still made a difference in people’s lives.

“What’s really cool about recruitment is even if you don’t actually donate, your commitment doesn’t end because you can get others to join,” Huinker says. “I recently got a message from a peer on campus who said, ‘I wanted to let you know I just got a call that I’m a match and you’re the reason I joined.’ I get goosebumps thinking about it. So, even if I don’t get to be someone’s match, if I get someone to join the registry who later donates, I had a hand in saving someone’s life. It’s 100% worth it.”

Coreas, who graduated from Iowa with a degree in public health in May, also hopes to get the call to donate one day.

“Remembering the fear my family felt, the fear of the unknown and what could happen, I would love to take that away from a family and give them hope,” Coreas says.

Four years later, Coreas’s father is in remission after two autologous stem cell transplants. Instead of using donor cells, doctors were able to use his own stem cells to replace damaged marrow.

“He is on the track of improvement, and it’s so amazing to see his strength and overall positivity,” Coreas says. “He always shines on.”

Debunking myths about marrow donation

One myth is that it hurts. When you donate marrow, it doesn’t hurt. After the procedure, your back is going to be stiff and sore for a little bit of time, but most people are back to their normal activities in a day or two after donating. It is a medical procedure, and what we want people to think about is, “Are you willing to have a sore and stiff back for a few days in exchange for giving the patient and their family a chance of a lifetime?”

The second myth is it takes too much time: I can’t do it, I’m a busy professional or college student. To be a marrow or stem cell donor, two days will be taken away from normal activities. One day is when they are first identified as a potential donor. We need to have them come see us and have a physical exam to be sure they are healthy. A few weeks later, they are going to give us another day when they donate. That is all the time involved for donation.

The third myth is it is expensive and costs money to donate. We have a very supportive program so there are no medical expenses to donate, but also there are no other expenses. Travel is covered for all of it. When the individual drives down for the physical, and then in a couple weeks to donate, we reimburse them for their mileage, food, hotel, kennel if they have a dog, and pay for the sitter if the donor has children. If the donor is a college student, and they want their mom to be with them and they are from California, we will fly the mom out to be with their son or daughter when they donate. It is a super supportive program because we honor, respect, and celebrate our donors. We want the experience of donating to be something special for them.

—Colleen Reardon, manager of the Iowa Marrow Donor Program; reprinted with permission from the Iowa Cancer Consortium

Alivia Linnekin, shown here with her mother, Denise, received a bone marrow transplant in 2019. The donor, Michaela Heys, a medical student at Des Moines University who grew up in New Sharon, Iowa, had joined the donor registry just months earlier, and donated bone marrow for Alivia at UI Hospitals & Clinics. (Photo courtesy of the Linnekin family.)

Making a special connection — through bone marrow and in life

Alivia Linnekin kept getting strep throat over and over. Her mom, Denise Linnekin, wanted bloodwork done because the antibiotics weren’t working long-term. Alivia was quickly transferred to Children’s Scottish Rite Hospital in Atlanta, where the then-7-year-old was diagnosed in March 2019 with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a type of blood cancer.

“After her first round of chemo, they thought she might need a bone marrow transplant,” Linnekin says. “They followed through with three additional rounds before we knew the transplant was the lifesaving move that we needed for her.”

The previous fall, Michaela Heys had started medical school at Des Moines University, where she worked with body donors in the anatomy lab.

“I’ve always been an organ donor, but I thought it was amazing these people had donated their bodies to science,” Heys says. “I was telling my parents about it over Christmas break, and my mom mentioned she had been on the bone marrow registry for 10 years. I immediately signed up, because why wouldn’t you?”

Heys joined the Be the Match registry in January 2019 and got the call that she had matched in May.

“Michaela joined just as we needed her,” Linnekin says. “It was amazing. She was about a 75% match, which was the greatest percentage we could have ever hoped for.”

Heys says she didn’t think twice about saying yes. She talked to her university dean because she knew she might need to miss some school.

“He said, ‘We’re going to make this happen,’” Heys says. “All my professors were great and said this was way more important than any test would be.”

Heys’s parents flew up from Texas to be with her during the procedure. She says she was sore for a few days after, but it wasn’t terrible. She likened it to soreness after a hard workout or the feeling of sitting on bleachers for a long time.

“I don’t even really remember what it felt like because it was so worth it,” Heys says.

“I still get emotional talking about it now. It’s incredible to know that you can do so little and save someone’s life.”

All Heys knew about the donation recipient was that it was a 7-year-old with AML. Linnekin says all they knew was that there was a donor.

Reardon says the program lets donors know how the patient who got their cells is doing, and if both parties consent, they are given each other’s contact information a year later. Before then, the donor and recipient can communicate anonymously — with an intermediary scanning letters to remove identifying information.

“I think we both tried to throw little secret facts in there to learn where we might be in relation to each other,” Linnekin says. “It was like a pen pal situation where we talked about our hobbies and likes and dislikes.”

Linnekin lobbied to get Heys’s information a bit before the one-year mark because they were having a bell-ringing ceremony for Alivia to mark the end of treatment and wanted to invite Heys.

Heys and Alivia connected via FaceTime before the party, so they knew what each other looked like, but Alivia didn’t know Heys was coming to Georgia.

“Alivia saw her and immediately jumped into her arms. It was beautiful,” Linnekin says. “Putting a face to the person who saved your child’s life is hard to put into words. There were lots of tears. There was lots of happiness.”

Heys says her tears started before she even saw Alivia.

“We got there early and were waiting in a parking lot near their home and I started to cry,” Heys says. “I couldn’t believe I was there and was about to meet Alivia and her family. And then I was hugging her and we just sat there hugging and crying for probably five minutes.”

Alivia and Heys continue to talk on the phone about once a week. Linnekin says Heys’s father, who along with his wife joined Heys in Georgia, kept saying how much Alivia reminded him of Michaela when she was little.

“Alivia felt an immediate connection with Michaela,” Linnekin says. “They have a special relationship.”

Now 9, Alivia is in full remission and back to doing all the things kids do. She especially loves to swim, which she wasn’t able to do during treatment.

“She had minimal side effects from the bone marrow transplant,” Linnekin says. “She’s really been the poster child for this experience.”

Heys says she wishes more people were aware of bone marrow donation and knew how easy the process is. From the cheek swab she did herself at home to having appointments set up, gas and hotels paid for, and multiple people checking up on her after the surgery, Heys says the whole thing was seamless.

“I feel like I didn’t do anything but show up for the surgery,” Heys says. “And it’s cool that I get to see other people sign up because of me. Even if they have only a one in 430 chance of getting the call, that’s one more person who can be saved.”

As for Linnekin, she says her family will forever be grateful to Heys, and hopes more people will consider the gift of bone marrow donation.

“You never think it will happen to you,” Linnekin says. “Donors are so important because you might be able to save someone’s life someday. It doesn’t cost anything, and it can make a world of difference.”

Join Be the Match

Did you know?

- Someone dies from a blood cancer every 10 minutes.

- 70% of patients who need a marrow transplant do not have a match in their family.

- The likelihood of finding a non-familial match ranges from 23% to 77%, depending on a person’s ethnic background.

- The Be the Match Registry includes 22 million volunteers.

- 1 in 430 people in the registry are actually called to donate.

- 80% of donors give peripheral blood stem cells.

Take your first step to being someone’s cure by registering with Be the Match today.

168

743

599

Overcoming a fear to save a life

Sam Stephens doesn’t like needles. He’s been known to pass out getting a simple blood draw.

But in August 2019, he spent six hours with needles in his arms to donate PBSCs.

“It was painless, and I had no issues,” Stephens says. “At the end of the day, the significance of what I did was way bigger than any apprehension I had. It was a chance to give someone more time. That’s an incredible gift, and I feel really fortunate to have been able to give it.”

Stephens joined the Be the Match registry in 2011 while a student at the University of Iowa. It was so easy that he actually forgot he signed up. During Dance Marathon’s Big Event later that year, he tried to sign up and was told he was already on the registry.

Eight years later, the 2015 political science graduate from Des Moines, who now lives in Kansas City, Missouri, got word he matched with a woman in Massachusetts.

Stephens got injections in Kansas City of a drug to increase the number of blood-forming cells in his bloodstream for five days before the actual donation, which took place at the DeGowin Blood Center in UI Hospitals & Clinics. PBSC donation involves removing a donor’s blood through a needle in one arm, passing it through a machine that separates out the cells used in transplants, and returning the remaining blood through the other arm.

“We were there from about 8 a.m. to 2 p.m.,” Stephens says. “My mom came along, and we watched TV and hung out and it went really quickly.”

Stephens says the injections in the days before the donation left him a bit sore, sort of like after getting a flu shot, but after the actual donation, he felt fine.

In February 2021, Stephens and the woman who received his cells began emailing each other.

“She’s doing really well now,” Stephens says. “It’s weird because I don’t feel like I did much. I just donated blood. She’s essentially said I saved her life; I don’t think I’ve truly comprehended it. I think it just goes to show how easy the whole process is and how everyone, especially younger people, should sign up to donate.”

Sam Stephens joined the Be the Match registry in 2011 while a student at the University of Iowa. Eight years later, the 2015 political science graduate got word he matched with a woman in Massachusetts. “It’s weird because I don’t feel like I did much. I just donated blood,” Stephens says. “She’s essentially said I saved her life; I don’t think I’ve truly comprehended it. I think it just goes to show how easy the whole process is and how everyone, especially younger people, should sign up to donate.” (Photo courtesy of Sam Stephens.)

Working to improve the odds for all races and ethnicities

Matching donors and patients for blood and marrow transplants is more complicated than it is for most organ transplants.

“With this type of transplant, we have to match the immune system because we’re making a whole new blood-making factory,” Reardon says.

Matches are made based on human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), proteins found on cells that the immune system uses to identify which cells belong and which do not. There are many HLA markers, and the more markers that a patient and donor have that match, the better.

It’s why only one in 430 potential donors actually ends up donating.

“We’ve seen patients who have multiple matches and others who have none,” Reardon says. “There are 38.7 million people registered worldwide, and there may be no matches. This is because certain tissue types are more common in certain populations than others.”

Patients are more likely to match a donor of their own race and ethnic background, and the likelihood of finding a donor is directly related to it. A white patient who needs a transplant has a 77% chance of finding a non-familial match, whereas a Black patient’s chance is 23%, and this is primarily due to the makeup of the registry.

“Patients who are mixed race have an even more difficult time,” Reardon says. “For example, if your dad is Chinese and your mom is Irish, the chances of finding a match go down dramatically.”

To improve the odds for everyone, the diversity of the donor pool needs to increase. Reardon and Be the Match student groups are working to reach out to groups on Iowa campuses to do just that.

“We want to fight to give every patient an equal chance to find their donor,” Huinker says. “Iowa State is a predominantly white campus, but we focus on reaching out to minority associations on campus such as the Multicultural Student Association, Multicultural Greek Council, and the National Panhellenic Council. We also screen the Mixed Match documentary about mixed race blood cancer patients looking for a donor on campus during non-COVID years.”

Likelihood of finding a match by ethnicity

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers used in matching are inherited. Some ethnic groups have more complex tissue types than others, making a person’s ethnic background important in predicting the likelihood of finding a match.

- African American: 23%

- Asian or Pacific Islander: 41%

- Hispanic or Latino: 46%

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 57%

- White: 77%

Coreas says along with working with similar organizations on the Iowa campus, she and her fellow students also have partnered with the cultural centers on campus.

“We explain why it’s more difficult to find donors for some populations and how we can keep those numbers up right here in Iowa,” Coreas says.

Reardon says the responses have been excellent, from students from minority groups signing up to donate to amplifying the message on their social media channels.

Through all the changes over the years and going forward into the future, Reardon says one thing won’t change: How rewarding it is to share the journey with donors.

“Every night on the news, we see what humans do to each other,” Reardon says. “I work with a subset of our population who donates bone marrow to people they don’t know. I mean, what a joy that my life is filled with these amazing, giving, loving people.”