A longtime fan of doo-wop, University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduate Emily Sieu Liebowitz became frustrated when she found background information elusive on groups such as the Shirelles and the Ronettes, despite their hit singles. So she decided to write a book.

Story: Sara Epstein Moninger

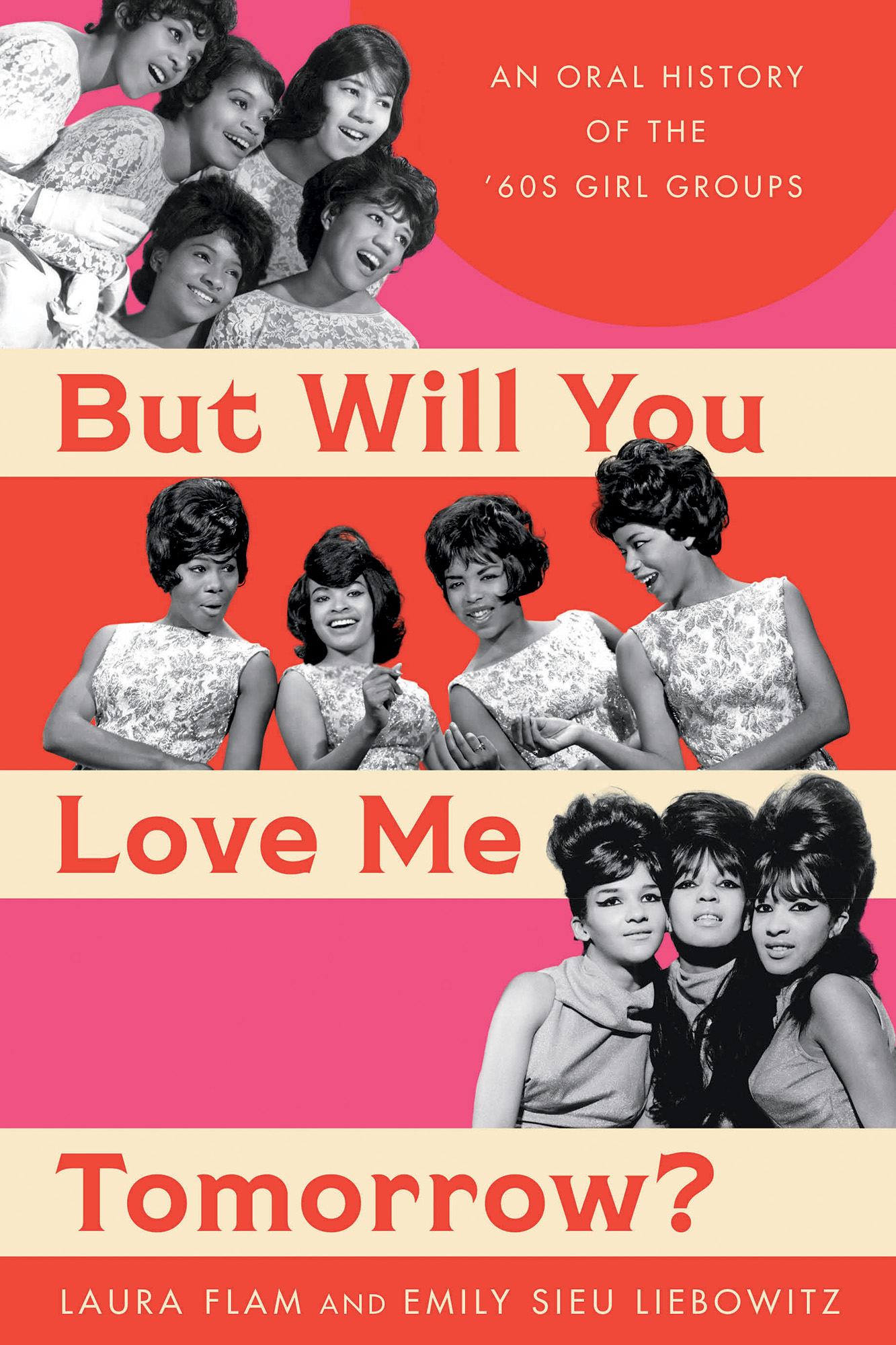

Photography: portrait courtesy of Emily Sieu Liebowitz

Published: Sept. 12, 2023

Emily Sieu Liebowitz grew up in the Bay Area grooving to oldies such as “Be My Baby” and “Then He Kissed Me,” so the University of Iowa graduate was thrilled when she met a friend in New York with similar musical tastes who was excited to attend shows with her. Curious by nature, Liebowitz was surprised that more information about popular women performers from the 1960s, some of whom were still touring, was not readily accessible.

“One of my all-time favorite songs is ‘Please Mr. Postman’ by the Marvelettes, but if you wanted to find information about the performers, you’d have a difficult time,” Liebowitz says. “We really wanted to learn more about these women, but there was nothing geared toward a mainstream audience. So we decided we should write about them.”

Liebowitz, who earned an MFA in poetry from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2011, teamed up with pal Laura Flam, an interior designer and fellow girl group aficionado, to tell the groups’ stories. Over three years, the duo conducted interviews with more than 100 subjects, from performers and producers to songwriters and sound engineers, and then compiled a narrative in But Will You Love Me Tomorrow?: An Oral History of the ’60s Girl Groups, published by Hachette Books in September 2023.

Although the book is a departure from her work in poetry, which includes her 2018 debut collection, National Park, Liebowitz says the experience has informed her writing. She shares what she learned from working on But Will You Love Me Tomorrow? as well as what’s next for her.

The book covers the Ronettes, the Shirelles, the Supremes, and many other popular groups. How did you determine the subjects?

We couldn’t interview everybody, so first we considered the songs we thought were important and then went to the groups. From there, we honed our questions, but we didn’t even know at the time what we needed to know—we kind of learned as we went. After reviewing the interviews, we started seeing patterns come together—different years, different parties, different relationships. We tried to give every group their moment and emphasize each group’s journey.

Laura would conduct the interviews, and I listened and suggested follow-up questions. I wasn’t at all the interviews, but I’ve probably listened to each one four to eight times. I also carved out the narrative. Having a workshop background really helped, because Laura and I had to ask each other tough questions about the manuscript, like “What’s not happening here?” and “What can we move around?”

What surprised you as you listened to these women’s stories?

How many different ways they were taken advantage of. I don’t know enough about the modern music business—I feel like I would have to take on a whole separate project to really understand it—or how much it has or hasn’t changed. But these women were just kids, many still in high school. I was surprised by what was expected of them and how much they worked. Putting them on a bus and sending them across the country didn’t seem like a good idea to me. I was also shocked to learn that a lot of songwriters didn’t own their copyrights and had to buy them back later.

Another thing is that women just were not considered something worth investing in, and I think that’s still true. There were expectations that they were going to leave the business and have children. I think most of them have children and are happy to have children, but it was more an expectation than a choice.

What do you want readers to take away from the book?

That the accomplishments of these singers and performers are incredibly valuable. They were on the forefront of so many things that we benefited from. They really pushed the needle forward for women’s rights, for example. “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” was cowritten by Carole King and recorded by the Shirelles in 1960. It’s a feminist song—it references premarital sex, literally asking a man, “What do you owe me for giving myself to you?” The birth control pill came out the same year.

The Shirelles, who were young Black women, also regularly desegregated places by performing concerts for both Black and white audiences—not necessarily knowing it or signing up for it. I hope that people can see through how we treated them in our culture and acknowledge their accomplishments, and that some people who were invisible but major contributors will be more visible. This music is some of the first nationally distributed pop music, especially from women, and because it’s not considered a serious genre of music, our fear is that it’s at risk for erasure.

How was your experience at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and in Iowa City?

Iowa City was the first place where I felt writing was valued—not just by the Writers’ Workshop or the International Writing Program or the English department or the thriving library, but also by my landlord and anybody I interacted with in the community. Everyone there thinks literature matters.

Having that time to focus on my writing felt like a huge gift. Everyone in the program assumes that you take writing as a serious, lifelong commitment, and I felt like I had permission to be a poet. I was exposed to different perspectives through seminars and conversations and visiting professors, and there were amazing bookstores and readings and writers coming through town. Being in the workshop solidified for me how I wanted to move forward in my life: with writing at the center of it.

What’s next for you?

I’ll always have my poems, but I’m also looking for projects that can challenge me and teach me things that I can bring back to my poetry. Currently, I’m working on an intergenerational memoir-esque thing called Motherland. It’s about my mom and my paternal grandmother, who raised me together after my father passed away, and it weaves in California history. It’s a really different type of writing for me, but I have been enjoying applying my poetry skills to prose and narrative.