Jorge Moreno is on a dizzying life ascent. The University of Iowa alumnus was born into a migrant family and entered Iowa as a first-generation student. After faltering initially, he has earned multiple degrees and now is a research scientist attempting to unlock the molecular secrets to immortality.

Story: Richard C. Lewis

Photography: Tim Schoon and courtesy of Jorge Moreno and Maurine Neiman

Published: Oct. 14, 2024

Forgive University of Iowa alumnus Jorge Moreno if his story seems straight out of a Hollywood movie script.

Born in America to migrant laborers, Moreno was first a boy who balanced work in the fields with his schooling, and later a first-in-his-family college student who was hurtling toward losing a vital scholarship. But he would find a faculty mentor and ally at Iowa and would go on to earn a doctorate, be first author on a recent study, and become a researcher who is studying the secret of immortality from a tiny jellyfish.

Sometimes, Moreno admits, he needs to remind himself that it’s all true.

“My journey from being a child of migrant laborers to having a doctorate is a story of resilience, curiosity, and opportunity,” Moreno says. “My life has been filled with many firsts and unexpected paths, but I’ve learned that success comes from the willingness to challenge ourselves.”

Moreno was born in Texas when his 21-year-old mother, at nine months pregnant, journeyed by herself to the United States to give birth. For the first several years of his life, Moreno and his family would leave Mexico to pick fruit or vegetables in the state where the produce was in season, rotating among Florida, Michigan, Texas, Georgia, and Iowa. Moreno barely saw his parents; they were like fleeting silhouettes when his slumber-filled eyes would flutter open at dawn or late at night. Fleeting, too, was school: Moreno barely would be in one place long enough to get acclimated to teachers, classmates, or classes.

“It was tough. We were always moving,” Moreno recalls. “But in some ways, it was good. It made me very adaptable.”

That adaptability would continue to be tested as Moreno grew older. By middle school, his family had narrowed its seasonal travels to two states: Texas and Iowa. But despite the reduced wandering for labor, Moreno shuttled between schools in both states; he’d join his school in south Texas in October, after fall classes had started, and return to Williamsburg, Iowa, after the upcoming year’s class schedules had been set. That meant, even unintentionally, he was regularly omitted from honors courses for which he had qualified via tests on which he scored higher than nearly all his peers.

“I remember feeling all this frustration, ‘What does it matter? Just put me into the right class,’” he recalls.

Compounding the scholastic snafus, Moreno needed to help his family. His senior year, he rushed at lunchtime from campus to the farm field, another hand to pick corn, another wage earner, a vital $7.25-an-hour addition to the six-member family’s bottom line.

Jorge Moreno gives two thumbs up while collecting specimens of a jellyfish called Turritopsis dohrnii off the coast of Panama last summer. The University of Iowa alumnus now works as a postdoctoral researcher at the Stowers Institute, where he wants to learn how the jellyfish can change stages in its life cycle.

“I knew we weren’t rich,” Moreno says. “I was needed as a contributor to the family because I could work.”

Thanks in large part to a dedicated principal at Williamsburg High School, Moreno eventually was enrolled in advanced placement classes. He thrived, especially in math and the sciences. Yet despite flourishing academically, Moreno didn’t give a moment’s thought to going to college. His first inclination was to join the Marines — and not tell his parents — but a high-school teacher in Texas bargained with him that Moreno would get a ride to the recruitment office only if he applied to some colleges.

One of those colleges was Iowa; Moreno relays with some mirth that he did so only after being informed by his guidance counselor at Williamsburg High School that Iowa’s early application deadline and instant acceptance decision meant Moreno would know his status before he left the Hawkeye state for Texas.

Iowa did something else that no other school that had accepted Moreno would do: It invited him to visit campus and offered him full tuition, based on his test scores, grades, and being a first-generation student.

“Iowa says, ‘We’re paying for your school.’ And, I was like, ‘Wow, that settles it,’” Moreno says. “That’s how I ended up going to Iowa. It was all kind of coincidental and convoluted. But it’s one of the greatest decisions of my life, for sure.”

Moreno’s decision didn’t seem like it would pan out. He struggled with the transition to college, especially in grasping the study habits needed to succeed academically. He was stretched thin working jobs to support himself — at the dining hall in Burge residence hall, a restaurant, and a cellphone repair store. His first-year grade-point average had fallen under 3.0, jeopardizing his scholarship.

“I started thinking, ‘I’m not cut out for this. Maybe I’m not good enough to be here,’” Moreno says.

Even though doubt had crept in, Moreno steeled himself and pivoted. He made friends with a few classmates who, like he, were on a pre-medicine track. One of them told him to look into research opportunities as a way to burnish his credentials. So, he reached out — and that’s how he met a biologist named Maurine Neiman.

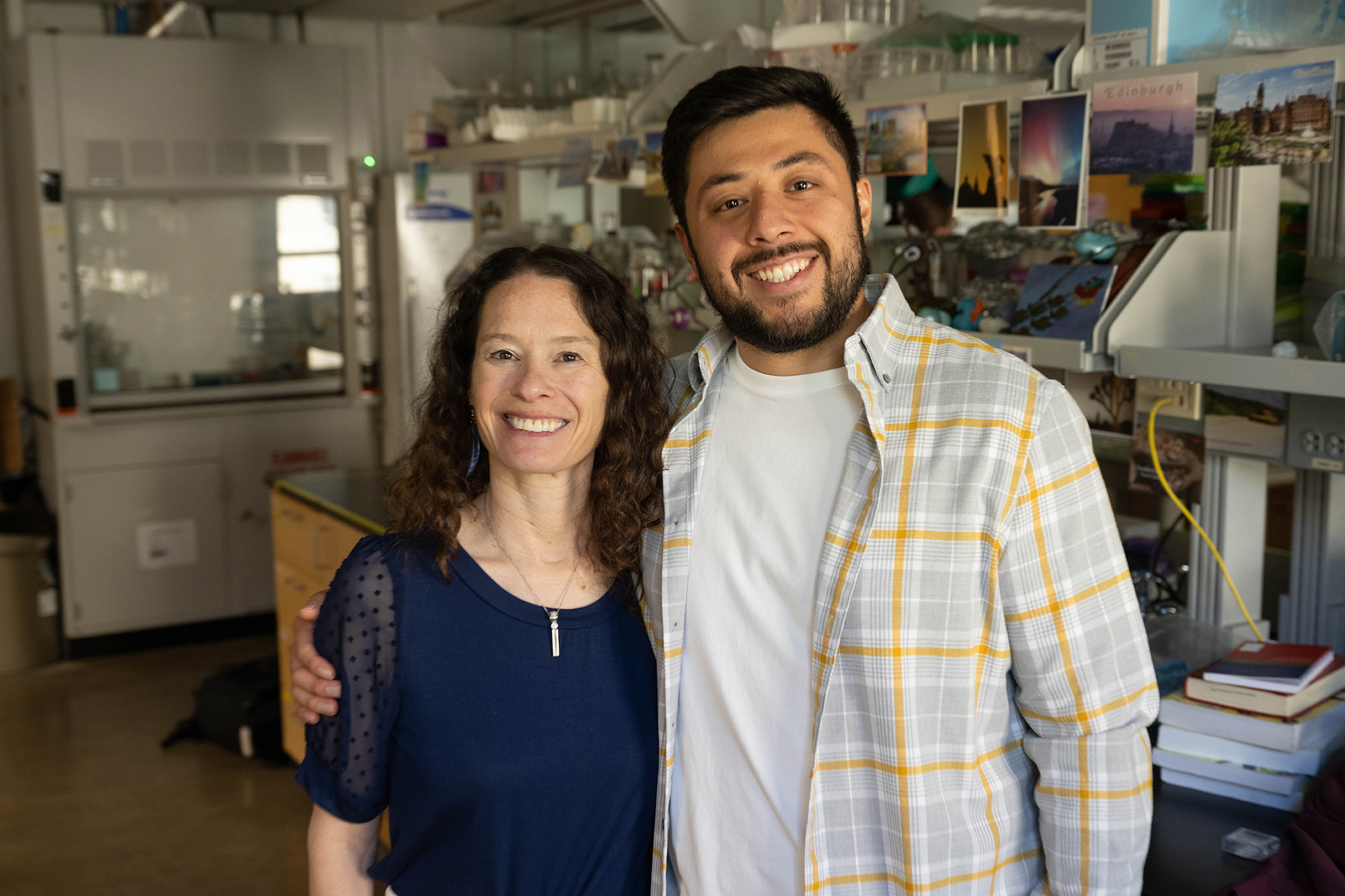

Jorge Moreno poses for a photo with University of Iowa faculty member Maurine Neiman during a visit to Iowa's campus in September 2024. Neiman was Moreno's mentor during his undergraduate days at Iowa. “Joining Maurine’s lab was one of those times when I was just able to be curious again,” Moreno says. “I was taking in a lot of new information. I was learning new things.”

When Moreno walked into Neiman’s office as a sophomore in fall 2015, he had no idea what she did as a scientist. And Neiman had little idea why Moreno was interested in her research. Yet despite the disconnect, the two sensed an almost immediate rapport.

Neiman says she overlooked Moreno’s typo-laden meeting request email and liked him right away. He was fun to talk to, genuinely curious, and confident in himself, she remembers.

“It was very clear he didn’t know what it would mean to be in a science lab,” says Neiman, a professor in the Department of Biology who studies the evolution of sexual reproduction, primarily using a New Zealand freshwater snail as a model. “But he just wanted a foot in the door, and after I met him, I wanted to give him that chance.”

Moreno seized on the opportunity. He started with general tasks assigned to undergraduates, such as feeding the snails. Rather than putting in his shift and leaving, Moreno went to the lab meetings. He asked the lab’s graduate students and postdoctoral researchers what they were doing, and why. He hung around the lab a lot — observing, absorbing, discovering.

“Joining Maurine’s lab was one of those times when I was just able to be curious again,” Moreno says. “I was taking in a lot of new information. I was learning new things.”

By late spring, Moreno had ensconced himself in the lab’s milieu, viewed less as a come-and-go student and more as a fixture in the group. So, one day, Neiman offered him a summer job in her lab. He would lead his own research project, she told him. And she would apply on his behalf for a U.S. National Science Foundation program that financially supports research opportunities for select undergraduates.

Maurine Neiman (far right) and her husband, Bennett Brown (second from left), attend a Moreno family quinceanera.

“Doing dedicated research in a science lab during the summer is such an important experience because it gives you a chance to really focus in a way that you can’t when classes and all these other things are competing for your attention,” Neiman says. “So, I thought it was a really important opportunity for him.”

The opportunity dramatically changed Moreno’s calculus. He could acquire more experience in research. He could take a summer class or two, advancing in his degree. He would be paid, meaning he could drop the extra jobs he had needed to pay the rent and feed himself.

“It set me on this track that I want to be a scientist,” Moreno says. “I spent all summer in the lab, working on my own project. I got to hang out more with the graduate students and talk a lot more with Maurine. It was fantastic.”

As he entered his junior year, Moreno was confident he wanted to be a scientist and to engage full time in research.

He asked Neiman, “How do I become you?”

“You need to go to graduate school,” she replied.

Problem was, Moreno hadn’t entertained that notion. So, Neiman helped him to identify graduate programs and faculty advisors who worked on the type of science that Moreno was interested in.

Neiman again went to bat for Moreno: She contacted the Iowa Sciences Academy and asked the principals to consider Moreno for a scholarship, even though he was not technically eligible as a junior and the application deadline had passed.

“I thought he should have a chance,” Neiman says, explaining why she intervened. “It was a program perfectly suited for his academic stage in life, his goals, and his ambitions. I told them, ‘Can you please give Jorge a chance? He is worth an exception.’”

Moreno won a scholarship. That meant he’d get paid to work 40 hours every week in Neiman’s lab. He could leave the extra jobs behind, concentrate exclusively on his coursework, and pursue his own burgeoning research interests.

“Maurine and everyone in the Iowa Sciences Academy made it their mission to help me progress in my undergraduate studies and strengthen my chances to get into graduate school,” Moreno says.

Moreno earned a Bachelor of Science in biology (with a subdepartment of evolutionary biology) in 2018. He attended Princeton University, earning a doctorate in molecular biology last January. His research focus during that time netted him first authorship on a study examining how three distinct, closely related species of marsupials evolved the same molecular formula for flying. The paper was published in April in Nature, one of the premier scientific journals in the world.

At the beginning of 2024, Moreno took another big step in his research journey, when he was hired as a postdoctoral researcher at the Stowers Institute in Kansas City, Missouri. He is studying a tiny jellyfish, called Turritopsis dohrnii, that can reverse engineer itself from an adult to a juvenile stage when threatened, then turn itself back into an adult when the danger passes. What Moreno wants to find out is how the jellyfish’s Benjamin Button–style transformation occurs on the molecular level, with the goal to reprogram fully developed human cells into anything that’s needed: an eyelid, heart tissue, you name it.

Jorge Moreno smiles for a photo in Maurine Neiman’s lab during commencement season in 2018. Moreno received a degree in biology from the University of Iowa.

“What the immortal jellyfish does is take cells that are fully differentiated, at the final stage of what they’re meant to be, and somehow those cells are capable of turning into something else,” Moreno says. “They give rise to a new structure entirely, and I’m interested in unlocking how they do that.”

It’s a moonshot-like pursuit. But those who know Moreno well are not surprised. They admire his courage, his tenacity, his will to overcome any obstacle tossed in his path.

“Jorge has chutzpah,” Neiman says. “He’s willing to try things that might fail, and he’s willing to try again and again and again. That’s who he is.”