Iowa biologist Andrew Forbes’ lab, with a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation, is revealing the unknown ecological world of parasitic wasps, which have value to cataloging biological diversity and controlling insect pests in agriculture and forests.

Story: Richard C. Lewis

Photography: Tim Schoon

Published: Oct. 17, 2025

Andrew Forbes held a small, woody ball found on a white oak tree and cut it open. Inside, cocooned within a tan, nougat-like layer, was a white sac.

“That’s a pupal wasp,” says Forbes, professor and associate chair in the Department of Biology at the University of Iowa. He extracted the pupa with tweezers and pointed to two black specks protruding from the fleshy chamber. “Those are going to be the eyes.”

The embryo Forbes showed was a parasitic wasp, which had coerced the tree to create the ball that had become the wasp’s incubator.

But that’s just the start: The oak-created ball, called a gall, and the wasp living inside each would attract its own set of marauding predators, thus spawning a churning, chaotic mini-ecosystem.

Forbes’ research team is investigating this host-parasite cascade to unravel the ecological and evolutionary mysteries of parasitic wasps, which have been largely understudied but have value to cataloging biological diversity and controlling insect pests in agriculture and forests. The group is using a nearly $900,000 award from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) to lead an effort to collect, study, and discover new oak gall wasps and their parasites. Iowa undergraduates and citizen-scientists throughout the nation are integral to the effort.

This pupal wasp, shown here in Andrew Forbes' lab, was housed within the gall that now lies split open.

Forbes expects the research to lead to the discovery of hundreds — maybe thousands — of new species of parasitic wasps, which would further his claim that they are among the most plentiful species on Earth.

“I think it’s really interesting to understand where new species come from and to see how it happens,” Forbes says. “It’s a basic science question, but I think it’s one that we should all be interested in.”

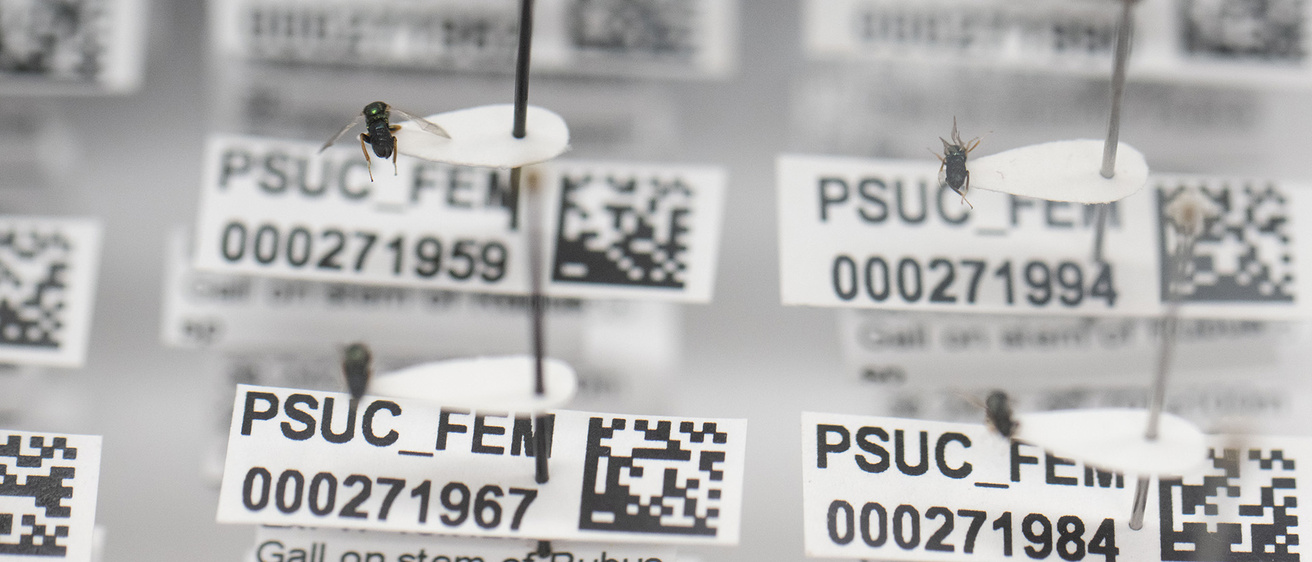

A few samples of hundreds of oak galls in University of Iowa biologist Andrew Forbes' lab. Oak trees create the galls after being coerced by parasitic wasps, who use them to lay eggs and grow their young. Forbes is studying galls to learn about parasitic wasps and to discover new species.

The hidden diversity of parasitic wasps

Parasitic wasps are one file card in Hymenoptera, the taxonomic order that includes ants, bees, and wasps. In that assemblage of insects, there are 150,000 described species, second only to Coleoptera, the order comprising beetles, which has 350,000 known species.

But that gap is narrowing, and discoveries of new parasitic wasp species is a big reason why. In the past few decades, scientists have found and detailed a dizzying array of parasitic wasps, many of them with fantastical tales of how they procreate, survive, and thrive.

There’s the crypt-keeper wasp, so named because it entombs another wasp and then eats it whole as it gnaws its way out to freedom. There are other parasitic wasps that seduce, or manipulate, insects, from caterpillars to spiders, into bizarre, trancelike states that seal their demise but allow the wasps to feed and live on. And, in these parasite-host transactions, there can be additional layers of parasitism — parasitic wasps that are preying on the original parasitic wasp, using it as a host to deliver its progeny.

Start to add it all up, and Forbes’ group is convinced there are a lot more species awaiting their moment of discovery.

“There are probably many hundreds more in the collections we have that need to be described, and we just haven’t had a taxonomist here to do that,” Forbes says.

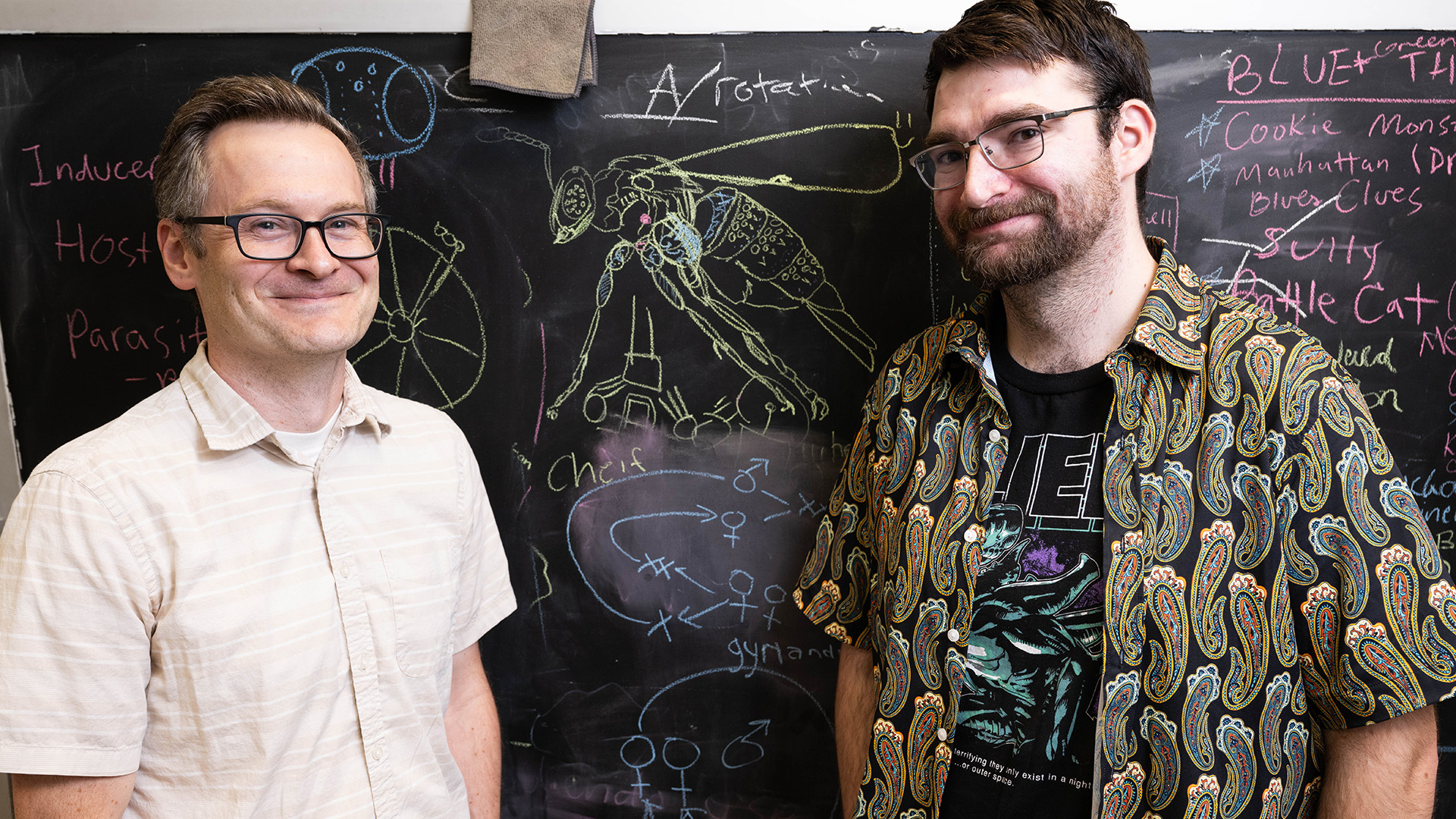

Andrew Forbes (left), professor in the Department of Biology, and postdoctoral researcher Louis Nastasi stand in front of a chalkboard in Forbes' lab. Nastasi drew the wasp on the chalkboard, which also includes potential names for any new parasitic wasp species.

The taxonomer in chief

In August, Louis Nastasi joined the Forbes lab to do just that. Nastasi earned his doctorate in entomology — the study of insects — from Penn State in May, and he had partnered with Forbes on a study in 2024 describing 22 new species of oak gall wasps in the genus Ceroptres. Nastasi christened these new taxonomic entrants with colorful monikers coined after their conniving abilities and any telling detail that stood out from their minuscule bodies.

“They’re essentially thieves, usurpers, and pirates,” Nastasi says, “so, we had some fun with their names, like Swiper the Fox, Jabba the Hutt, and Cat Woman.”

Nastasi is in charge of going through Forbes’ extensive collection of oak gall wasps and their associates, primarily in the genera Ceroptres and Ormyrus, the latter of which, Forbes and his team reported in a 2022 study, were actually new wasp species so specialized that each chose a different gall wasp species to hack into and turn into its host.

To identify new species, Nastasi will look at gall wasps’ physical features under a high-powered microscope and also sequence their DNA.

“Only by going through this comprehensive process of sequencing, looking at their morphology, and understanding which galls they attack on which plants, can we unearth the number of species, name them, and provide details on how to identify them from each other,” says Nastasi, who worked with insect collections as an undergraduate at Case Western University and later at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

When a new species has been identified and described, it will get a name. Already, the research team has been brainstorming, writing potential names on a whiteboard set in the middle of the lab. The theme is green and blue, mimicking the body coloration of the Ormyrus genus; so far, the group has whipped up a real range, from the Hulk to Cookie Monster — names that likely will be scientifically embroidered with a Latinized ending.

“It’s kind of a reward after doing all the hard work of figuring out what they are, how they’re different from each other,” Nastasi says. “You get to decide which name best fits a specific species. There’s no other job like this.”

Louis Nastasi’s 5 favorite wasp names

Ceroptres jabbai (in family Cynipidae) – “I named this species after Jabba the Hutt from Star Wars because it has the most known host species of any member of its genus, which evokes the greed and opulence of Jabba’s palace in the movies.”

Kikiki huna (in family Mymaridae) – “Its name is derived from the Hawaiian word for ‘tiny,’ which is extremely appropriate, as adult wasps of this species measure just 0.15 millimeters long! The small size of this species makes it the smallest known flying insect.”

Euderus set (in family Eulophidae) – “Described by previous members of the Forbes Lab in 2017, this species chews its way through its host to exit its gall. It is named after the Egyptian god Set, whose mythos mirrors this life cycle nicely.”

Microgaster godzilla (in family Braconidae) – “This species is named after the iconic Godzilla due to its life cycle. This wasp hunts caterpillars that live underwater and drags them onto land to parasitize them. This resembles Godzilla’s dramatic emergence from water in many scenes, and the battle between the parasitic wasp and its host is reminiscent of kaiju battles seen throughout the Godzilla films.”

Idris elba (in family Platygastridae) – “The genus name Idris already existed before this species was first identified, so the describers had the perfect opportunity to make the species name correspond to the well-known actor.”

Sammi Chronister, a sophomore at the University of Iowa, comes to Andrew Forbes' lab at least twice a week to look for wasps or other insects that have emerged from oak galls. The Cedar Rapids, Iowa, native says finding a wasp is "like a child seeing a puppy for the first time."

The undergraduate students on discovery’s front lines

The Forbes lab relies on undergraduates to take the important, intermediate steps to a potential new species discovery. On the Friday afternoon of Homecoming weekend, as hordes of students took to the streets of Iowa City, Sammi Chronister was in the Forbes lab on the second floor of the Biology Building, pulling cups of white oak galls from a refrigerator packed with hundreds of gall specimens. Chronister, a sophomore from Cedar Rapids, opens each cup and looks for any gall wasps that have emerged and any other parasites or insects that are around.

“If I see literally anything moving around in here, then I grab it,” she says.

Any wasp or other living thing she finds will be deposited into an ethanol-filled tube that is labeled according to the gall and the tree species that produced it.

Chronister transferred to Iowa this fall after studying two years at Kirkwood Community College. She comes into the Forbes lab at least twice a week. The work is calming, she says, and the thrill of finding a wasp never wanes.

“It’s fascinating,” she says, “like a child seeing a puppy for the first time.”

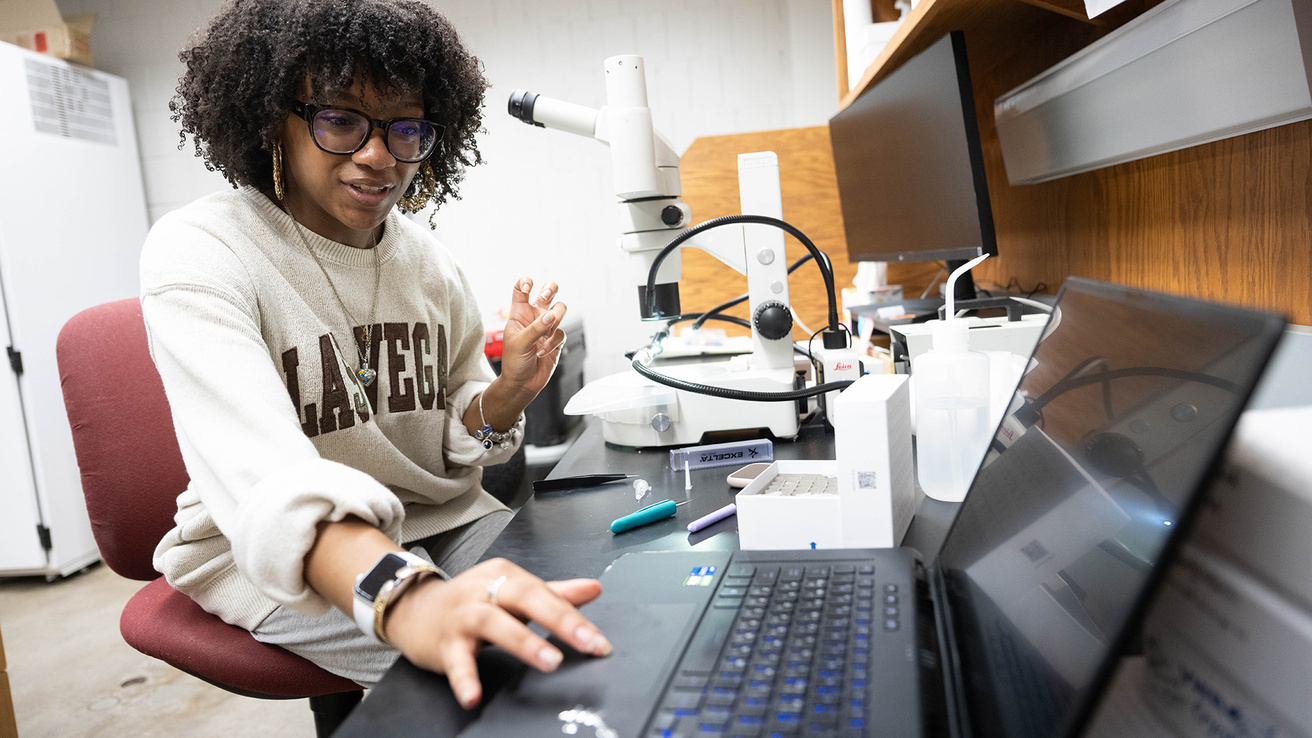

Amil Brown, a senior from the Quad Cities, uses a high-powered microscope to examine the physical features of parasitic wasps, so she can properly identify the wasp's genus and its placement in the taxonomic order.

A few feet away from Chronister sits Amil Brown. The senior operates a high-powered microscope to peer at a wasp on a slide. She uses tweezers to gently reposition the insect, so she can see every detail on its 3-millimeter-long body.

Brown believes the wasp she’s examining is from the family Pteromalidae — black, metallic green, or bronze-colored insects constituting a branch of the Chalcid superfamily. The physical features distinguishing family members are subtle; Brown consults a computerized database of Pteromalidae and a 1997 book about Chalcids for clues. Her aim is to identify the wasp’s genus so its taxonomic order can be clarified and so scientists can understand more about how they interact with galls and the greater environment.

“It’s like solving a puzzle, in a sense,” she says.

Brown’s family had moved to the Quad Cities as she finished high school in Washington state remotely. She learned about Iowa by perusing the university’s offerings in environmental science, the subject that interested her the most. She liked that the university offered a wealth of experiential learning that would take place outside the classroom. She decided to enroll.

“Lo and behold, when I got into my environmental science major, they have BioBlitz classes and prairie restoration courses,” Brown says. “I was like, ‘This is perfect.’”

Amil Brown, a senior at the University of Iowa and a member of Andrew Forbes' lab, consults a computerized database of wasps to verify a specimen's genus and taxonomic classification.

She started in the Forbes lab as a junior, after hearing a presentation that fall about the ecology of gall wasps from Guerin Brown, a graduate student working on a doctorate in integrated biology. Smitten by the topic, Amil Brown emailed Forbes the same day asking to join his lab.

“It’s just such a wild little world that I want to learn more about,” she says.

Brown started by helping a graduate student identify a type of fly collected through field traps. She then partnered with Guerin Brown to identify wasps that had emerged from galls. Within six months, she had earned her current role.

“Even though I was nervous when I began, all the lab members were very sweet and gave me the opportunity to learn more, while being able to grow my experience and skills,” she says.

The job has fulfilled her intellectually and scholastically.

“Being on the forefront of research is something I dreamed of doing ever since I was a kid,” Brown says. “I was thinking, by the time I grow up, everyone’s going to discover everything by now. But to know that there are areas out there that are undiscovered, it feels fun being a part of that.”

Sophomore Sammi Chronister carries a stack of cups containing oak galls. Chronister and other undergraduates working in Andrew Forbes' lab check out cups for signs of wasps or other insects that have emerged from the galls.

The scientist addicted to wasps

Forbes can relate. He was a graduate student at the University of Notre Dame investigating a fly that had become so dependent on using an apple to procreate that it had evolved into a new species. As he studied the fly-host apple interactions, he noticed wasps were emerging from the maggots. Could these wasps, like the fly, be a parasite so specialized that it was a new species, too?

“I got addicted to wasps,” Forbes says. “I liked working with them rather than the flies, mainly because no one else was working with them. It was my own little biological system to play around with.”

That addiction has catapulted Forbes into a leading voice in the debate over which animal group is the most species-rich on the planet. Beetles have been the front-runner for centuries, thanks to their size (they can be easy to find and catalog), their riot of colors and appendages, and Charles Darwin’s and others’ fawning descriptions about their collections. That thinking took a turn when Forbes declared in a 2018 study that his research with parasitic wasps was showing there is a vast number of undiscovered species, and he predicted wasps would surpass the beetles order by at least two-fold.

“While there are more described species of beetles than all other animals, the Hymenoptera are almost certainly the larger order,” Forbes and his co-authors wrote.

Now, they need to find those new species. Thankfully, they have a citizen army to help them.

“I think it’s really interesting to understand where new species come from and to see how it happens. It’s a basic science question, but I think it’s one that we should all be interested in.”

Let’s all hunt galls!

People around the United States collect and identify galls through Gallformers.org, a site that was created independently and has been expanded through the NSF funding won by Forbes.

Beth Burrous is one of the gall hunters. The Arlington, Virginia, resident and retired patent attorney began looking for oak galls around her neighborhood as part of a pilot project for the Forbes lab in 2023. A nature lover, Burrous searches for galls at least once a week.

“It’s kind of like finding buried treasure,” she says.

Burrous collected specimens in Arlington National Cemetery, Rock Creek Park, and the National Arboretum in Washington D.C.; and spots in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maine, and sent them to the Forbes lab. She and others also share their finds on the website iNaturalist.

“This is a way that I can contribute to the progress of science and learn about the natural world,” she adds.

Forbes sees himself in the gall hunters. They’re curious, and so is he. They seek a deeper understanding of nature, and so does he. They revel in each new find, and so does he.

“I just think finding out new things about the natural history of these animals is just really interesting,” he says. “And there’s clearly a lot of people out there who think so, too.”