Husband, wife hearing the world around them better

Roberta Carver woke up the morning of Feb. 11, 2021, and couldn’t hear anything in her right ear. Sudden inflammation in her ear caused hearing loss. It also made her nauseated and resulted in balance issues. Further, she also developed severe tinnitus, or ringing in the ear.

After a course of steroids and a couple months of physical therapy, Roberta and her husband, Jim Carver, drove from their home in Alburnett, Iowa, to University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics. They saw Marlan Hansen, MD, otolaryngologist and head of the UI Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and Camille Dunn, PhD, director of cochlear implants at the Iowa Cochlear Implant Clinical Research Center.

“She was really distraught,” Dunn says. “She didn’t have any speech understanding in that ear. The tinnitus was really bothering her and significantly affecting her quality of life.”

Hansen told Roberta she was a candidate for a cochlear implant in the ear that had lost hearing.

“I said, ‘What about my husband?’ He’s had 100% hearing loss in one ear for 10 years,” Roberta says she told Hansen.

A cochlear implant is an electronic medical device for individuals with moderate to profound hearing loss that is designed to restore the ability to perceive sounds and understand speech. Unlike a hearing aid, which amplifies sound, a cochlear implant bypasses the damaged hair cells in the inner ear (cochlea) to deliver sound signals directly to the auditory nerve.

Cochlear implants use a sound processor that fits behind the ear to capture sound signals and send them to a receiver implanted under the skin. The receiver then sends the signals to the electrodes implanted in the inner ear. The brain interprets those signals as sounds.

It can take time and training to learn to interpret the signals received from a cochlear implant, but most people make considerable gains in understanding speech after several months.

Jim left that day with an appointment of his own. Roberta got her cochlear implant in June, and Jim followed with his in October.

“I could not believe it. I mean, holy smokes, there was sound in this ear, and I have been functioning without it for a long time,” Jim says about the moment his implant was activated. “It was just amazing to be able to hear in it again.”

Jim started losing hearing in one ear 20 years ago but lost all hearing in the other ear fairly suddenly about a decade ago. While hearing aids helped some in the better ear, they didn’t do anything for the other.

“When we went in for his last hearing aids, I asked, ‘Isn’t there something you can do?’” Roberta says. “And they said no, you have to be deaf in both ears to be eligible for a cochlear implant. So, we didn’t pursue it any further.”

Hansen and Dunn say this is an unfortunate but not uncommon response. While cochlear implants traditionally were used to treat patients with complete hearing loss in both ears, patients with complete or partial hearing loss in one ear increasingly have become candidates for the devices in recent years.

Only 5% to 10% of people with hearing loss who could potentially benefit from a cochlear implant, however, have one. Hansen and Dunn say there are several reasons for this, including a lack of widespread awareness of the expanded candidacy rules.

“We often have patients come in and say, ‘I just don’t know what else to do. I can’t hear,’” Dunn says. “There are lots of techniques that we have pioneered at the University of Iowa that have allowed us to expand candidacy and help more patients who are struggling with hearing aids become candidates for cochlear implants. But there’s still a lack of understanding about the expanded guidelines. We’re working with professionals in the field to provide them information and resources to better know when they should refer patients on to us for evaluation.”

“I could not believe it. I mean, holy smokes, there was sound in this ear, and I have been functioning without it for a long time. It was just amazing to be able to hear in it again.”

The Carvers both have cochlear implant sound processors that clip into their hair. “Roberta combs my hair over it and she makes me look good—if you didn’t know it was there and looked for it, you wouldn’t see mine,” Jim says. “I have a granddaughter who’s 5 and she never said anything.”

For 40 years, the pioneering work of experts at the UI-based Iowa Cochlear Implant Center has transformed the lives of generations of patients who are deaf and have hearing loss.

“For many years, we never really considered using cochlear implants for hearing loss in just one ear because we thought the brain would not be able to use the sort of artificial sound from the implant without messing with the other ear’s ability to understand,” Hansen says.

Hansen says cochlear implant experts knew that cochlear implants were fairly effective in suppressing tinnitus, so a group in Europe tried giving a small group of patients with unilateral hearing loss and severe tinnitus a cochlear implant.

“They didn’t go in with the idea of necessarily improving their hearing, just treating the tinnitus, but lo and behold, the patients heard better,” Hansen says. “The FDA approved one company’s cochlear implants for single-sided deafness in 2019 and since then it’s being used more and more and more. A second company’s implants received FDA approval for unilateral hearing loss in the past few weeks.”

Experts at the University of Iowa have transformed the lives of generations of patients who are deaf and have hearing loss as pioneers in cochlear implants for more than 40 years.

In 1980, the department implanted its first adult with a single-channel cochlear implant, and in 1987, Bruce Gantz, MD, longtime UI professor of otolaryngology and neurosurgery, inserted a multichannel cochlear implant into the first congenitally deaf child in the U.S. In 2020, Gantz became the first in the world to insert a cochlear implant using a robotic device developed by Iowa researchers, including Marlan Hansen, head of the UI Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.

Hansen says there are still plenty of questions to be answered regarding how cochlear implants can help people hear better.

“The field is rapidly changing and there’s a lot that’s under development,” Hansen says.

Hansen says much is being done around assessment of the ear and its condition using imaging before, during, and after surgery to determine the best electrode and location to place it. They also are looking at how the brain processes speech from regular hearing, speech from damaged ears, speech from electrical signals such as those from cochlear implants, and speech from combined electrical and acoustical stimulation.

A new clinical trial is examining using electrodes in cochlear implants that deliver drugs to the inner ear to prevent inflammation that can damage hearing.

While still a way down the road, there’s also a movement toward completely internal cochlear implants, meaning people wouldn’t have to wear an external sound processor.

Two big issues researchers are looking into involve genetics and dementia.

“We’re doing a lot of work around genetics to figure out if there are genetic ways to predict how people might do with a cochlear implant,” Hansen says. “Dementia is also a significant area of research. Hearing loss is now recognized as one of the major factors for dementia, so we’re trying to figure out if early intervention with cochlear implants may be beneficial and help prevent dementia.”

Meanwhile, researchers at Iowa pioneered the use of hybrid cochlear implants, which are used for people who have severe to profound high-frequency hearing loss but still have a significant amount of low-frequency hearing. The device is implanted only in the part of the cochlea that transmits high-frequency sound and allows the person to continue to make use of their residual low-frequency hearing. In this way, they hear with both natural, acoustic stimulation for low-frequency sounds coupled with electrical stimulation from the implant for higher-frequency sounds.

Jim says he’s not that surprised he started losing hearing in one ear a couple decades ago.

“I was a PE teacher, a football coach, wrestling coach, track coach. In a small school you get to do everything,” Jim says. “I blew the whistle. Kids yelled and screamed at pep rallies in a small gym. I knew I was going to go deaf eventually.”

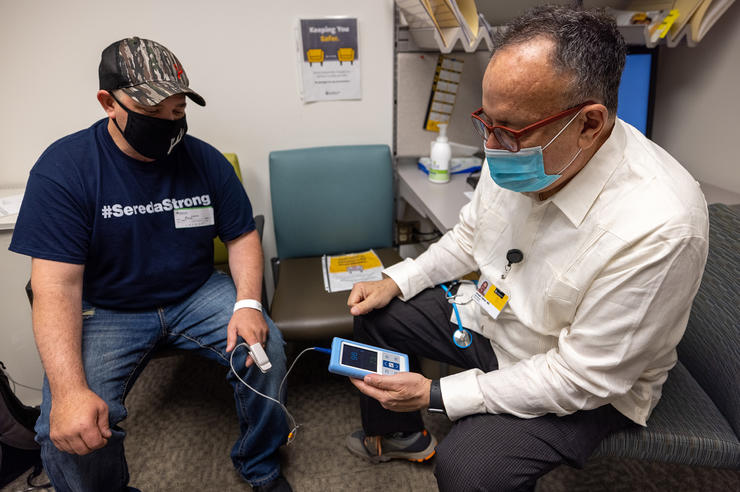

Patients undergo extensive testing to determine if they are candidates for a cochlear implant. The first step is to make sure their hearing aids are fitted appropriately. Their hearing is then tested with their hearing aids and used as a baseline.

“Based on all the information we get, we can help them understand whether or not a cochlear implant may benefit them,” Dunn says. “We can say, ‘I don’t think the cochlear implant will make you better,’ and then work with them to find ways to improve their hearing with their hearing aids and potential rehab and additional assisted listening devices. Or we can say, ‘Yes, I think with a cochlear implant that there’s a very good opportunity that you’ll get better speech understanding than what you’re getting with your best-fit hearing aids.’”

Before receiving a cochlear implant, patients are counseled about what to expect during and after the surgery. This includes what hearing with a cochlear implant will sound like.

“Patients at first describe it as sounding like a chipmunk, or Darth Vader talking underwater, or that sounds are muffled,” Dunn says. “But the brain is an amazing, amazing organ. It will start interpreting it as sounds the person once recognized. So, their wife’s voice, or their own voice, might not sound like it did right away. But after they start doing their listening exercises, over the next couple months, that voice will sound more and more like how they remember it sounding.”

Jim says he and Roberta are putting in the work and doing their hearing therapy.

“It’s maybe not happening as fast as we would like to have it happen, but it’s happening and we’re improving,” Jim says.

“We often have patients come in and say, ‘I just don’t know what else to do. I can’t hear.’ There are lots of techniques that we have pioneered at the University of Iowa that have allowed us to expand candidacy and help more patients who are struggling with hearing aids become candidates for cochlear implants.”

Roberta says her hearing isn’t quite as far along as Jim’s. In December, she was fitted with one of Jim’s old hearing aids—he still uses one—and it was paired to her cochlear implant. This way, when she talks on her mobile phone or uses other devices, it will be like earbuds and she’ll hear everything through the hearing aid and the cochlear implant. Dunn says it should help with some of the disparity Roberta was experiencing between the two ears.

Dunn says Roberta and Jim will likely use their cochlear implants differently.

“Jim still has some hearing in one ear and uses a hearing aid, but he’ll likely rely on his cochlear implant for hearing and understanding speech,” Dunn says. “Roberta, however, still has decent hearing in one ear, and she’ll probably focus on the good hearing ear and use the cochlear implant to supplement the good hearing ear.”

Camille Dunn, PhD, director of cochlear implants at the Iowa Cochlear Implant Clinical Research Center, says there has been an uptick in patients seeking help for hearing loss over the past year and a half.

“We’re seeing probably three times the number of patients we did prior to COVID,” Dunn says. “And the main reason for that, I think, is the face masks. People couldn’t get by reading lips. They realized, ‘Wow, my hearing is really bad. I didn’t realize how much I was lip-reading and how much I needed that.’ So that kind of pushed people in the direction of seeking help.”

Treating a married couple is unique now, but Hansen doesn’t think it will stay that way.

“This likely will become a more common scenario because we’re finding that cochlear implants can benefit more and more people,” Hansen says. “So as more people become candidates, more people become aware of it, and our population gets older, it’s going to become less of a novelty that you see a husband and wife who might both benefit from a cochlear implant.”

The Carvers say they were warned about potential temporary side effects after the implant surgery, including balance issues and nausea, both of which they experienced. Jim also has numbness in his tongue and an altered sense of taste, but he’s hopeful that will subside over the next couple of months.

“The nurses and doctors there have been very helpful,” says Roberta, who notes that UI Hospitals & Clinics works hard to coordinate their appointments so they don’t have to make multiple trips to Iowa City. “They respond quickly and call to check up and give us information. And Christine Pett and Colin Lyle, Cochlear manufacturer representatives, also often check in and ask how things are going. It’s good to know that we have all those supports.”

While the Carvers’ hearing continues to evolve with their new cochlear implants, Jim says he’s already feeling more like himself.

“I am a people person,” Jim says. “I want to talk. I want to be around people. And I did not in any way, shape, or form want to be one of those people that said, ‘Yeah, yeah, I get it,’ and not hear a word that was being said. And there were times when I didn’t hear and I would have to ask, ‘What are you saying,’ or ‘Say that again.’ I still don’t pick up all the words, but I’m doing my hearing therapy and I think I’m doing really well for going from not hearing anything to even being able to hear words and everything.”