Offering answers and support

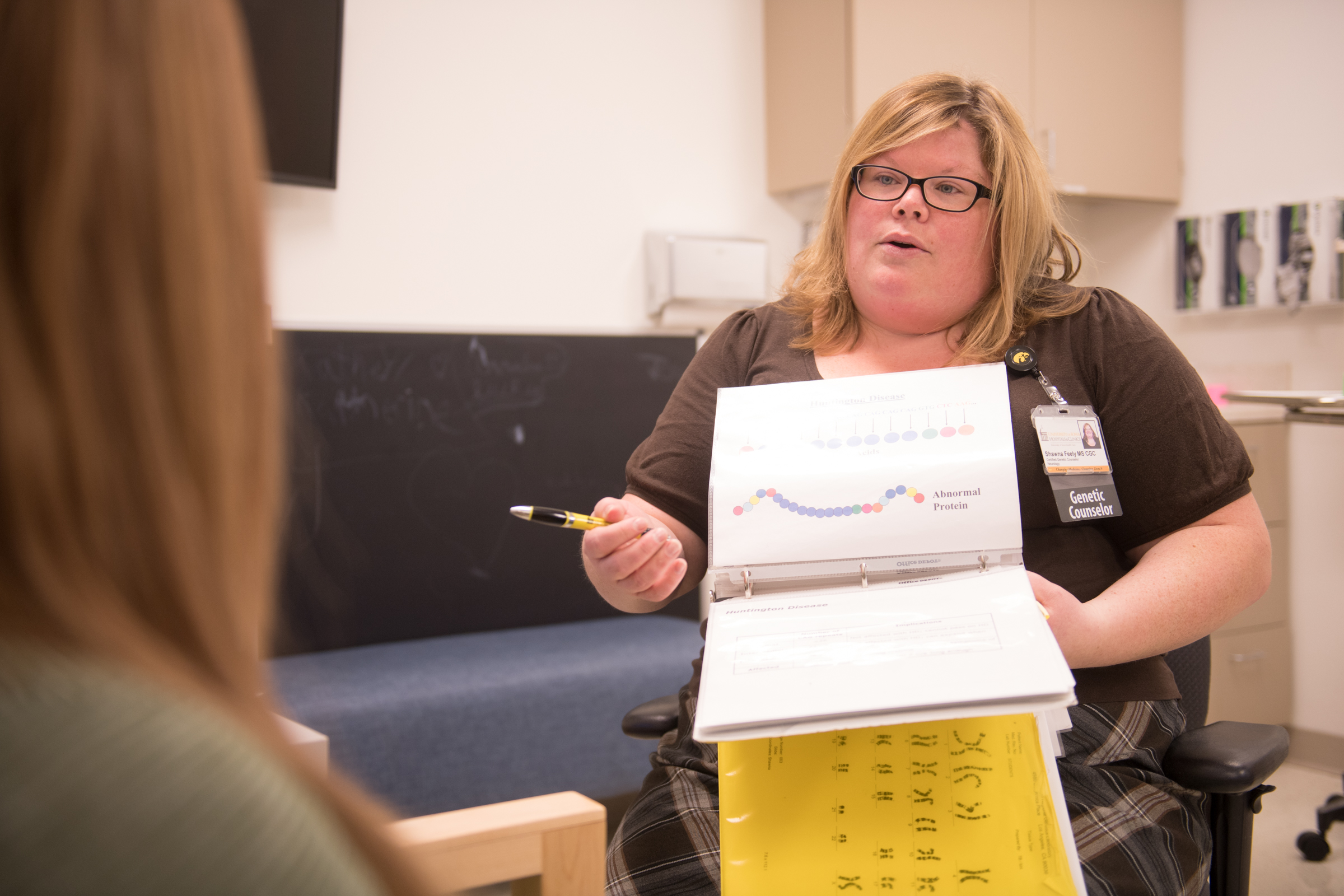

When Shawna Feely started working at the University of Iowa in 2012, she was one of eight genetic counselors employed on the UI Health Care campus. Today, she is among 20.

With our increasing understanding of the human genome, improvements in screening technology, and the popularity of direct-to-consumer DNA-testing services, the demand for people who can help navigate the genetic landscape has skyrocketed, whether in a clinical setting or in a research lab.

“Diseases don’t happen in silos. We need to cross over and include others in care management to figure out how to effect change. If we work together, we can do that faster.”

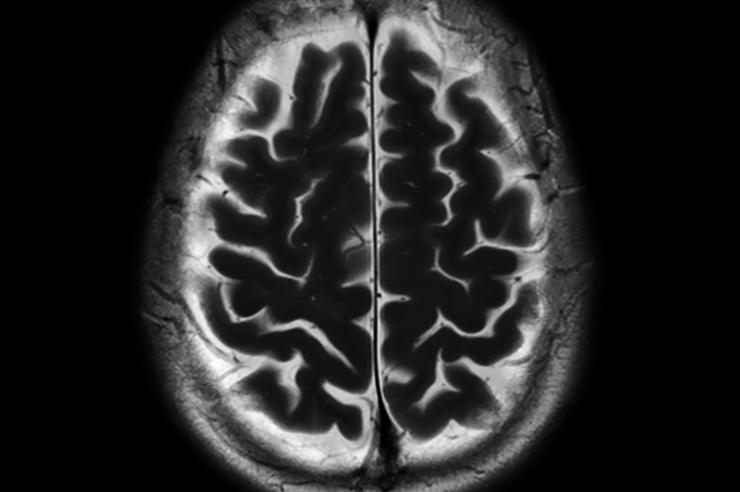

As a certified genetic counselor specializing in neurology, Feely works with people who have a family history of neurological disorders—especially Huntington’s disease, a progressive and incurable brain disorder. She sees as many as 15 patients a day at UI Hospitals and Clinics, guiding them through all phases of genetic testing.

“Finding out how you might die has implications for your life, from financial planning to family planning. We try to help people with the decision-making process by supporting them through education and emotional support,” she says. “We often end up serving as the point person throughout their care—we see them at the beginning of testing, check in with them afterward, and continue to work with them after they go home.”

Several things should be considered when deciding whether to test for the likelihood of developing a heritable disease, Feely explains: What will you learn from the test, what will you do with the results, and will having the results improve the quality of your life? Other aspects to keep in mind include which test should be selected, how much it will cost, whether insurance covers the expense, and how the results will be communicated to family members. Working as part of a health care team, genetic counselors guide patients through these questions and more.

“The sessions can get pretty heavy,” says Feely. “There are a lot of emotions either way. People may feel damaged or abnormal with a positive result. It can also be surprisingly emotional to receive a negative result. You might be the only sibling without a particular gene and end up with survivor’s guilt. While we can’t control the test results, we can guide the process—even determining which day of the week would be best for the patient to receive the results.”

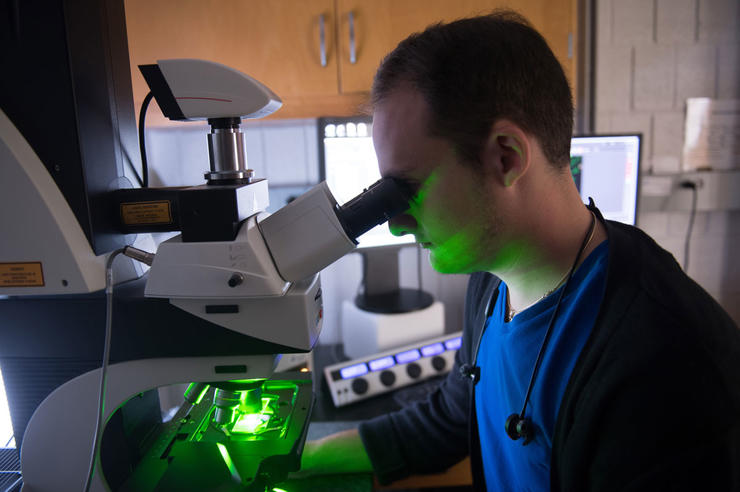

Established in 2012, the Iowa Institute of Human Genetics at the University of Iowa promotes clinical care, research, and education focused on the medical and scientific significance of variation in the human genome. It serves as a resource for all UI faculty and staff, as well as to the public.

According to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projections, employment of genetic counselors will grow by 28 percent between 2016 and 2026, faster than the average for all occupations. An estimated 4,000 genetic counselors work in the U.S., and only 41 accredited master’s programs in genetic counseling exist in the U.S. and Canada. The UI does not yet have a graduate program in genetic counseling—establishing one is a long-term goal, Feely says—but it has assembled a team of genetic counselors with specialties in neurology, women’s health, cancer, nephrology, pediatrics, and cardiology, and Iowa offers a competitive summer internship that gives college students and recent graduates an opportunity to shadow the UI genetic counselors and get hands-on experience in the field.

Colleen Campbell, director of genetic counseling operations at UI Hospitals and Clinics, says the UI is a national leader when it comes to growing a team of genetic counselors and is touted for its integrative approach.

“The leaders at UI Hospitals and Clinics recognize genetic counseling as a value-added service for patients as well as faculty and staff, and that has enabled us to be more progressive. By embedding genetic counselors in specialty areas across the hospital, we can better meet the needs of both patients and physicians,” she says. “There are 10 new genetic tests launched every day. It’s hard for physicians to keep up. The genetic counselors bring genetics expertise to the health care team. They help the providers use available testing as a tool in their practice and ensure the quality of the testing.”

Although Feely says she could take a job anywhere, she and colleague Michael Shy, UI professor of neurology, pediatrics, and molecular physiology and biophysics, chose to relocate their clinic for patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease, a group of inherited nerve disorders, from Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, to the UI. The collaborative atmosphere at Iowa was key, she says.

“Diseases don’t happen in silos,” Feely says. “We need to cross over and include others in care management to figure out how to effect change. If we work together, we can do that faster.”