Offering care across the spectrum

The teenager was in bad shape, physically and emotionally, when Dr. Katherine Imborek first met him.

The 17-year-old patient recently had been hospitalized for psychiatric treatment and broken bones after jumping from his second-story window in a suicide attempt. Born biologically female but identifying as male, he grappled with profound gender dysphoria—severe distress caused by a disconnect between a person’s birth-assigned sex and gender identity.

The boy’s mother was desperate. For years she had tried to get her son help, but doctors back home had little experience with transgender patients and were unequipped or unwilling to provide care. It wasn’t until the mother and son arrived at University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics, home of the state’s leading LGBTQ health clinic, that they found a path forward.

- Routine physical exams and wellness

- Same-day urgent care visits

- Chronic management of anxiety and depression

- Contraceptive management

- Gynecological services, including breast exams, pelvic exams, menopause care, and obstetric care

- HIV testing and prevention

- Sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment

- Hormone therapy

- Immunizations

- Post-surgical care following gender affirming surgery

Since its founding in 2012 by Imborek and fellow University of Iowa alumna Dr. Nicole Nisly, the UI’s LGBTQ Clinic has served more than 1,200 patients from across Iowa and the greater region, nearly 75% of whom identify as transgender or gender non-conforming. Because of social stigma and discrimination, transgender patients have historically been marginalized by the health system and often denied services, making it difficult for many to find welcoming and affirming providers. Because UI Hospitals & Clinics was the first in the state to offer comprehensive care for the lesbian, gay, transgender, queer, and questioning population—and today is one of just a few such providers in Iowa—more than 60% of the UI’s LGBTQ Clinic patients come from outside of Johnson County. Some travel as many as six hours for appointments.

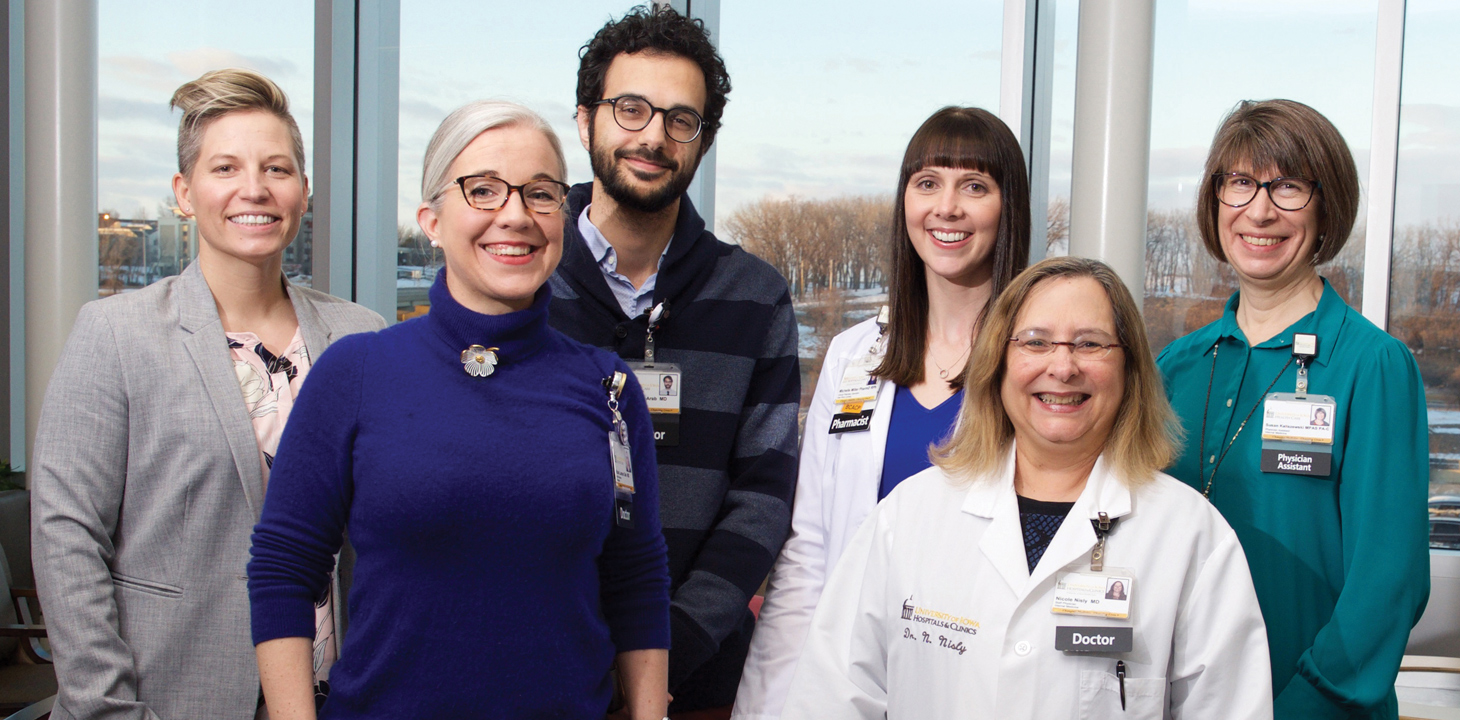

Headquartered in UI Hospitals & Clinics’ Iowa River Landing site in Coralville, the clinic is made up of a core team of four primary care physicians, a pharmacist, a pediatric endocrinologist, and several physician assistants, medical assistants, and nurses. The clinic partners with plastic surgeons, psychiatrists, gynecologists, and urologists from across UI Health Care. Named an LGBTQ health care equality leader by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, the clinic provides a safe environment for patients in need of everything from routine health screenings to hormone therapy to gender affirming surgery.

“Many of our patients are at risk of being left by their families, their partners, their children,” says Nisly, a professor of internal medicine. “There are a lot of losses that can be associated with coming out as a transgender person. Having a welcoming place where you can explore that is very significant. For many people, this is the first place where they can talk about it.”

Dr. Katherine Imborek, LGBTQ Clinic co-founder

Dr. Nicole Nisly, LGBTQ Clinic co-founder

Life-changing treatment

While Imborek sees dozens of patients a week, the suicidal teen with the broken bones and shattered spirit made a lasting impression. The doctor shares the boy’s story as an example of the difference the clinic makes in patients’ lives daily. “Oftentimes we see patients who are despondent because they’ve been estranged by their family, kicked out of their homes, or bullied,” says Imborek, an associate professor of family medicine. “But this poor young man had a super supportive mom, and just couldn’t find a doctor to treat him.”

During that first consultation, Imborek connected the teen and his mother with the clinic’s pharmacist, who discussed the risks and benefits of testosterone treatment. If the patient went forward with injections, his body would slowly develop the masculine features to match his gender identity. He’d develop a deeper voice and facial hair, and his muscle bulk might increase. At the same time, the evidence is unclear whether hormone therapy could elevate the risk of heart disease, liver disease, and diabetes, among other potential side effects.

The decision was an easy one for the family. A clinic nurse showed him how to self-inject the hormones, and he received his first dose of testosterone that night. Although it would take months for physical changes to occur, the emotional effects were immediate. His menstruation soon subsided, and so too did the suicidal thoughts.

There were plenty of tears that night at the clinic, recalls Imborek. Tears of joy, relief, and gratitude. As the doctor describes it, the boy had taken his first step toward becoming his authentic self.

A population in need

Imborek understands all too well the marginalization felt by many of her LGBTQ patients. In the early 2000s, Imborek was a student at a small liberal arts college in her native Indiana, where she studied kinesiology and sports medicine and was captain of the basketball team. She was also a lesbian. When it came time for Imborek to apply for medical school, her academic adviser offered a word of advice: Don’t mention your sexual orientation in your interviews. Coming out, cautioned the adviser, could keep you from getting in.

Far from holding back her career, Imborek’s commitment to LGBTQ advocacy instead dovetailed with her passion for medicine. She choose the UI for medical school and stayed in Iowa City—which has long been recognized as an LGBTQ-friendly community—for her residency and a faculty post in family medicine. As a medical student, Imborek launched an LGBTQ student health organization that hosted educational events and provided a support network for aspiring medical professionals. Imborek still serves as faculty adviser for the group, which is known today as EQUAL Meds.

Imborek met Nisly one night in 2011 at a panel discussion about transgender health care at a downtown Iowa City hotel. Nisly was a veteran physician who at the time was serving as the university’s chief diversity officer. She attended the discussion because she had recently begun seeing a patient who was transgender, and she felt ill-equipped to provide adequate care.

As Nisly listened to the panelists that night, she was appalled to hear their firsthand accounts. Some told stories of doctors refusing to use their preferred gender pronouns, or even their names, while others talked about being denied appointments because they were transgender. But Nisly’s dismay soon gave way to inspiration. When the event was over, she introduced herself to Imborek, who was also in the audience. Nisly explained to the junior faculty member that her Department of Internal Medicine had been tasked with establishing night clinics at the hospital’s soon-to-open Iowa River Landing location. “Are you interested in partnering to open an LGBTQ clinic?” Nisly asked.

“Many of our patients are at risk of being left by their families, their partners, their children.”

With support from then-UI President Sally Mason and hospital leaders, the LGBTQ Clinic opened in October 2012. Imborek and Nisly saw patients on Tuesday evenings on the Iowa River Landing building’s fourth floor, where one of the first orders of business was replacing the male and female bathroom signs with unisex placards. While the clinic was marketed to all LGBTQ patients, working with transgender people soon became the physicians’ primary focus. That’s because transgender patients—who suffer from significantly higher rates of anxiety, depression, and attempted suicides than the general population—tend to face the greatest barriers to health care. According to a 2015 survey of more than 200 transgender Iowans by the National Center for Transgender Equality, 34% reported a negative experience with a health care provider in the previous year, while 41% reported suffering from serious psychological distress in the previous month. Nearly one in three patients said they did not see a doctor when needed for fear of mistreatment for being transgender.

“We noticed in the beginning that people would come in and be very scared,” Nisly says. “They would sometimes be shaking in anticipation due to their past negative experiences. With time, as the community of patients grew because of word of mouth, it’s fair to say our patients now feel very comfortable in the clinic. That’s what we aimed to do—create a home for the transgender and gender-nonconforming community in general, including their families.”

Early on, there were questions about whether patient demand would be enough to justify a one-night-a-week LGBTQ clinic. Today, Imborek and Nisly’s team serves patients daily across three UI Hospitals & Clinics locations and partners with experts across the university. That includes the College of Education, whose doctoral students in marriage and family therapy provide free counseling services for patients undergoing hormone treatments or preparing for sex reassignment surgery. Transgender patients also receive voice training at the UI’s Wendell Johnson Speech and Hearing Clinic and support from the College of Law, where students and faculty help transitioning patients update birth certificates, driver’s licenses, and other legal documents.

“For me, it’s akin to someone who delivers babies,” Nisly says. “It’s so rewarding to work with people who have waited their whole lives to be congruent with who they are. To be part of that process is quite touching. That’s why you enter medicine—to help people.”

Embracing identity

Candice Thalken, a 65-year-old transgender woman, is among the patients who have transitioned under the clinic’s care. Growing up in a family of six sisters, Thalken was 8 when her mother first caught her shaving her legs. Still, she lived most of her life as a male. As an adult she went through seemingly endless cycles of buying women’s clothes, wearing them behind closed doors, then purging them in shame. Thalken, who never married or had children, came out as a trans woman a decade ago to a few close friends, but otherwise lived a life of “hiding and fear,” as she puts it.

Inspired by celebrity Caitlyn Jenner’s public transition in 2015, as well as internet support groups, Thalken decided the time was right to transition two years ago. Under Nisly’s care, Thalken began hormone therapy, and in recent months underwent a facial feminization procedure and a sex reassignment surgery called an orchiectomy. Today, living openly as a female, she says she’s grateful to the LGBTQ Clinic for helping her, for the first time, be comfortable in her own skin.

“They’ve made me as happy as I’ve ever been in my life,” says Thalken, who works in housekeeping at UI Hospitals & Clinics. “Hopefully in the future you’ll never find someone like me, because they will be able to get help so much sooner and not have to go through a whole lifetime of hiding.”

The LGBTQ Clinic Support Fund helps improve access and quality of care for UI patients and their families. The fund benefits areas like counseling services; access to personal items for transitioning patients like makeup, chest binders, and voice training; and continued LGBTQ-focused training for UI faculty.

Tori Castillo, 37, is a nine-year army veteran who fought in two wars, was married and divorced, and has “done all the manly stuff,” as she puts it. Still, Castillo—a transgender woman living in a small eastern Iowa town— had known her entire life that she was different. “I was always drawn to more feminine things. I grew up with the notion that it was taboo, so I pushed it aside for years and hid it, like most people do.”

Castillo’s inner turmoil left her in a dark place, she says, and the combat veteran for years battled mental health issues. After researching what it meant to be transgender two years ago, she called the LGBTQ Clinic for help. She began seeing Imborek, as well as a counselor, who provided her with the letter of recommendation necessary to begin hormone therapy. The clinic generally requires patients to undergo at least one evaluation from a mental health professional to discuss their gender history and the risks and benefits of transitioning genders. The therapist can then provide a letter of support for testosterone or estrogen treatment or recommend additional counseling.

“It was a huge relief,” says Castillo of taking those first steps toward transitioning. “It was basically like a sigh—like the universe was lifted off me.”

Since then, Castillo has undergone two facial feminization procedures to soften her features, including plastic surgery on her nose, cheeks, and lips. She’s also received a hair transplant, eyelid lift, and a jawline reduction, and has plans for laser hair removal and a possible sex reassignment surgery down the road.

“For patients who have gender dysphoria because of certain body parts, surgeons not only make a big difference in quality of life, but they can also be lifesaving,” Nisly says.

The doctor recalls a patient who arrived for a first appointment at the clinic with a detailed suicide plan tucked into a bag. After beginning treatment, the patient ripped up the plan.

A model for care

Dr. Rami Boutros, medical director for UI Hospitals & Clinics’ Iowa River Landing operations, says Imborek and Nisly’s important work furthers the hospital’s mission of providing accessible care to all Iowans and patient populations. “They’re passionate about medicine and what they do, and they’re very compassionate,” says Boutros. “They’re also great educators, which is the other part of our mission. They not only educate our students and residents, but also other health care providers to help them open their doors to LGBTQ patients.”

Iowa Magazine, produced by the UI Center for Advancement, has no shortage of stories that showcase the amazing talents of the University of Iowa community.

The UI team has served as a resource in recent years for numerous Iowa organizations that have established similar programs, including new LGBTQ clinics at Iowa State University, the Iowa City VA Health Care System, and the Iowa Department of Corrections. It’s also worked closely with doctors at UnityPoint Health, which opened LGBTQ clinics in Des Moines and Cedar Falls. In the classroom and through resident training, Imborek and Nisly prepare the next generation of physicians to provide medically competent and culturally humble LGBTQ care.

The ultimate goal, says Nisly, is to ensure that no matter where a patient seeks out care, a doctor is there who can help. “What we do should not be exceptional, but should be the standard of care,” she says.

This past spring, Imborek and Nisly stood at a podium inside a Coralville conference hall, not far from their Iowa River Landing clinic, where colleagues from around the state showered them in applause. The Iowa Medical Society honored the doctors with its community service award at the organization’s annual president’s reception. The moment was one Imborek couldn’t have imagined all those years ago, sitting in her academic adviser’s office.

“Going from a place where identifying as a lesbian would keep me from getting into medicine to now being given awards for working with LGBTQ people is the most wonderfully ironic turn of events,” Imborek says. “Every day I have to pinch myself because I get to work with this community I call my own.”