The birth of the traveling trophy known as Floyd of Rosedale wasn’t just a silly wager between two border-state governors. It was a conciliatory gesture in the wake of the 1934 game, in which the Hawkeyes’ Ozzie Simmons, who was Black, suffered numerous injurious hits.

Story: Tom Snee

Photography: Iowa Digital Library, University Archives; Tim Schoon

Published: Nov. 5, 2021

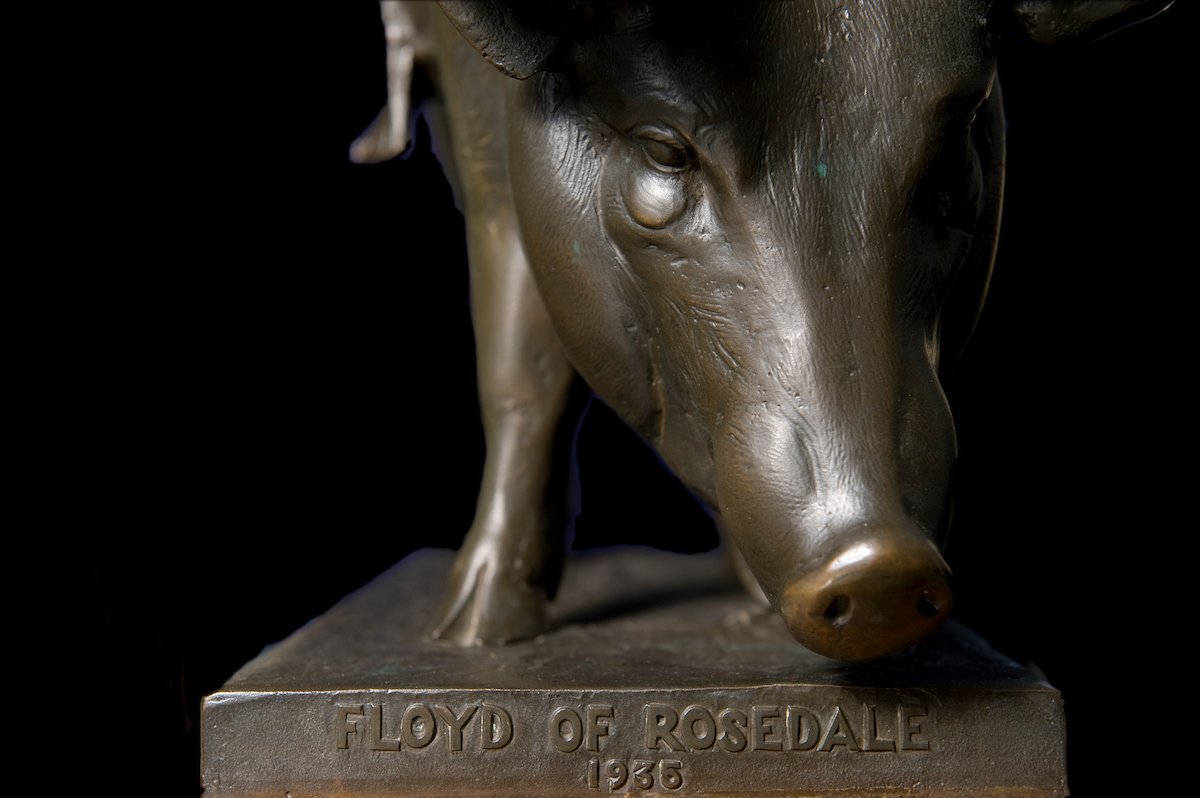

Most Iowans know about Floyd of Rosedale, the bronze pig coveted by the Iowa Hawkeyes and Minnesota Golden Gophers each fall. After the football game’s final whistle, the victorious team hoists the heavy statue into the autumnal sky, parading Floyd toward the locker room before he takes up residence in a trophy case and soaks up the spotlight at state fair exhibits.

This highly recognizable traveling trophy adds intensity to the annual clash. But Floyd of Rosedale’s “origin story”—in which the states’ governors wagered an actual prize hog—was meant to have the opposite effect: to ratchet down heated emotions surrounding the Iowa-Minnesota game in 1935, which featured two of the nation’s top programs battling for the Big Ten title.

The source of the simmering tensions? Controversy from alleged racial baiting in the 1934 game by Minnesota players against the Hawkeyes’ Ozzie Simmons, who was Black.

Simmons was a native Texan unable to play college ball in his home state because of his race. So, legend has it, he came to Iowa City in a boxcar to play for the Hawkeyes and soon electrified the team as a running back and punt and kick returner. In his first varsity game in 1934, he rushed for 166 yards against Northwestern, returned a kickoff for a touchdown, and added 124 yards in punt returns.

“When he left the game in the fourth quarter, newspapers reported that Northwestern fans gave him a standing ovation,” says Iowa alumna Jaime Schultz (MA ’99 PhD ’05), a professor of kinesiology at Penn State University who wrote about the racial angle of Floyd’s history in her PhD thesis at Iowa and also published a paper on the game, “A Wager Concerning a Diplomatic Pig,” in the spring 2005 issue of The Journal of Sport History.

But later in that 1934 season, Minnesota roughed up Simmons so badly that he was knocked unconscious three times and left the game before halftime. (None of the injurious hits was penalized.) Schultz said that while his injuries garnered media attention as one of the reasons for Minnesota’s 48-12 victory, few reporters outside the Black press speculated on the nature of the brutal hits. She said a Cedar Rapids Gazette columnist wondered whether the hits were based on the fact Simmons was Black, a charge dismissed by the Minneapolis Tribune, and that was the extent of it.

Until 1935. In the run-up to that season’s game at Iowa Stadium, Iowa governor Clyde Herring brought up the charges of cheap shots against Simmons from a year earlier and decried the Gophers’ violent tactics against him. Then, raising the specter of fan vigilantism, Herring said “if the officials stand for any rough tactics like Minnesota used last year, I’m sure the crowd won’t.”

Minnesota coach Bernie Bierman saw this as a threat and reacted accordingly. Schultz said Bierman threatened to never play Iowa again, and moved his team’s pregame practice to Rock Island, Illinois, where they were guarded by Illinois police he believed would be more neutral.

With the rhetoric growing more heated, Minnesota governor Floyd B. Olson decided it was time to cool things down. On Nov. 9, 1935, he telegrammed Herring a token of conciliation…

“Dear Clyde, Minnesota folks excited over your statement about the Iowa crowd lynching* the Minnesota football team. I have assured them that you are a law-abiding gentleman and are only trying to get our goat. The Minnesota team will tackle clean, but, oh! how hard, Clyde. If you seriously think Iowa has any chance to win, I will bet you a Minnesota prize hog against an Iowa prize hog that Minnesota wins today. The loser must deliver the hog in person to the winner. Accept my bet thru a reporter. You are getting odds because Minnesota raises better hogs than Iowa. My best personal regards and condolences.”

—Floyd B. Olson, Governor of Minnesota

* Schultz notes the use of such a regrettable word at a time when lynchings against Black people were all too common in the United States.

“It’s a bet,” Herring replied, and with that as a distraction, the game was played without incident. Simmons was “treated neither gingerly nor with excessive roughness,” Schultz says. Newspaper coverage made only brief mention of the controversy, focusing instead on the game itself and Olson’s unusual offer. When the Gophers won 13-6, Iowa was out one pig.

Simmons played one more troubled season in 1936, enduring what many in the press speculated was racially based mistreatment from Iowa coach Ossie Solem and his own teammates. While Simmons never made any public comment, many observers felt his teammates frequently left him unblocked and open to vicious hits. He even left the team for a time, although again, never made any public statement as to why.

Despite his greatness, he was never named team captain, and kept out of the NFL by the league’s color barrier*. He played for the American Association’s Paterson Panthers in New Jersey for two years (1937 and 1939) before retiring from professional football. He taught physical education in the Chicago public school system for 38 years, and died Sept. 26, 2001, of complications from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, according to an obituary in the Chicago Tribune.

* The NFL’s color barrier was put in place only a few years earlier, after the retirement of Duke Slater, an All-American player at Iowa and, as of 2021, the namesake of the field at Kinnick Stadium.

Simmons’ role in the creation of Floyd of Rosedale is often overshadowed by the politicians partaking in the big-pig bet.

“Media accounts disseminate popular knowledge about Floyd of Rosedale in which the protagonists are the two governors, and not Simmons,” Schultz says. “The catalytic moment in the tale is the wager, and not Simmons’ injuries. In these ways, the trophy has come to symbolize a long-standing, healthy rivalry between two Midwestern states, rather than reminding us of racism in the region’s, and indeed the country’s, sporting past.”