Recognizing excellence in the humanities

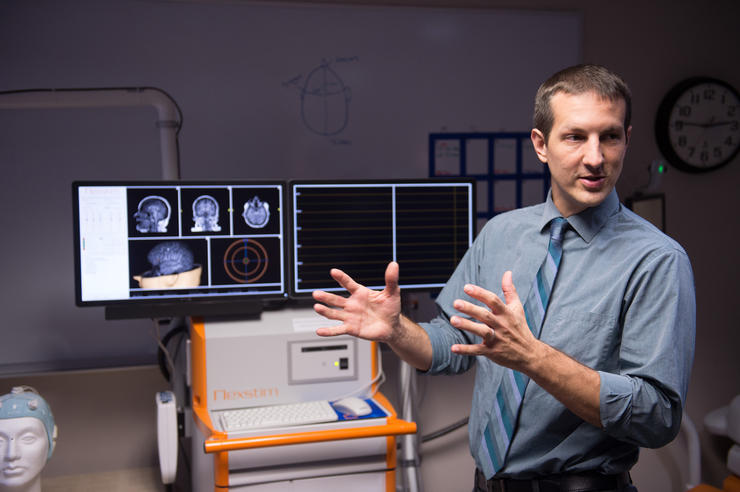

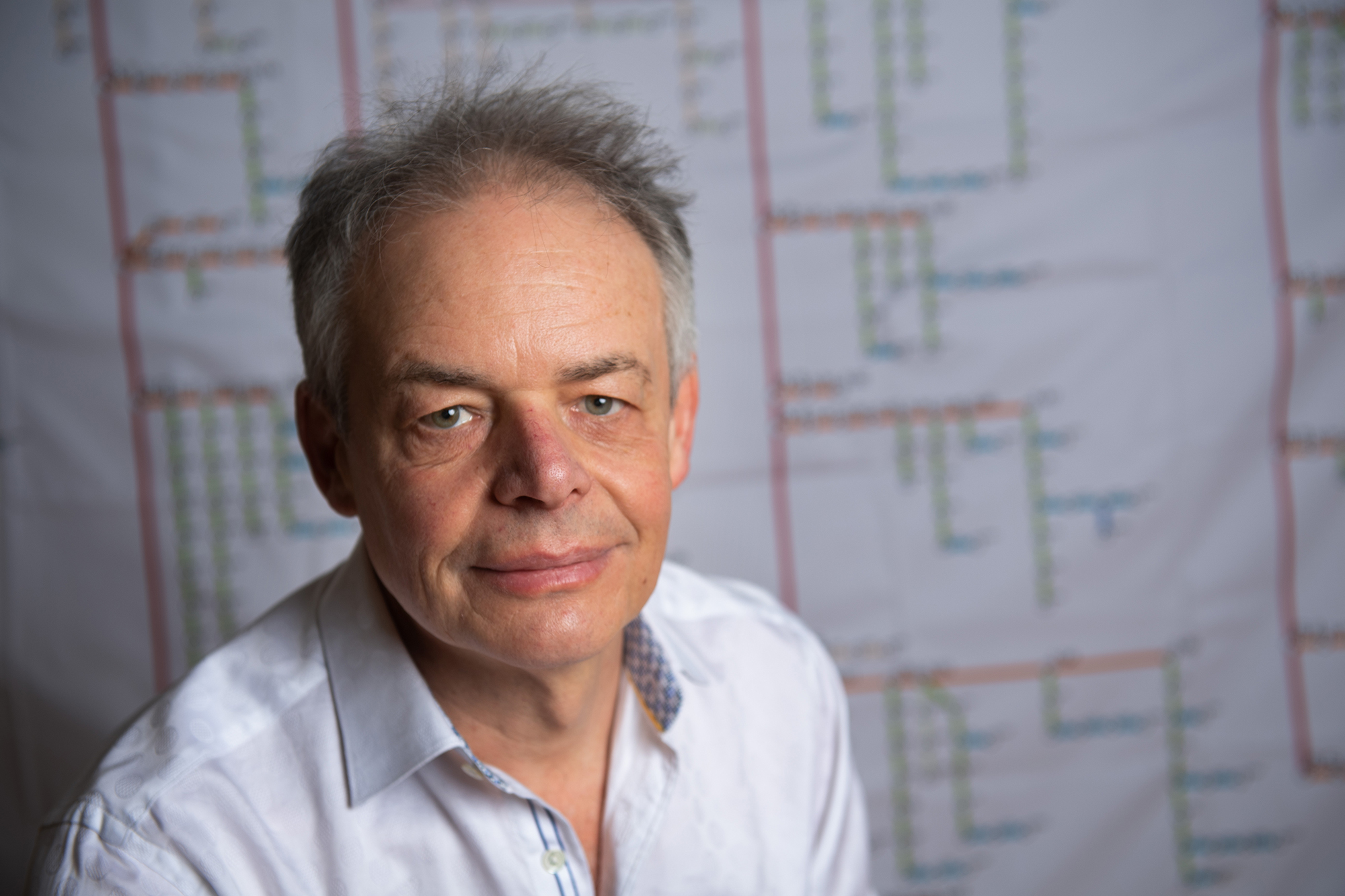

University of Iowa faculty David Stern (left) and Simon Balto, recipients of National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grants for the 2020-21 awards cycle.

University of Iowa faculty have consistently received National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grants since the awards’ inception in 1965. Funded projects have focused on history, religion, literature, archaeology, and music, among myriad others.

In January, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (CLAS) faculty Simon Balto and David Stern joined that prestigious list after being notified their NEH proposals had been approved.

“I was pretty stunned, honestly,” Balto says. “These grants are so competitive, and when you apply, you’re up against so many other accomplished scholars. To have any overwhelming confidence that yours would be one of the successful applications seems a bit silly. To actually receive one is wild.”

With the NEH’s recognition of Balto and Stern, Iowa joins a select list of institutions to receive more than one grant in the same cycle.

A total of 55 UI faculty have received grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities since the awards’ inception in 1965. Recent recipients include:

2017: Katina T. Lillios, for the completion of a book-length archaeological survey of the prehistoric Iberian peninsula

2016: Ellen Lewin, for an ethnographic study on the experiences of black LGBT Pentecostals who belong to the Fellowship of Affirming Ministries

2015: Luis Martin-Estudillo, for a book in progress titled Spanish Culture and the Rise of Euroskepticism (1939–2013)

2012: Linda K. Kerber, for Why Diamonds Really Are a Girl’s Best Friend: A Comparative History of the Legal Doctrine of Coverture

2011: H. Shelton Stromquist, for a book-length transnational, comparative study of the municipal origins of independent labor politics from 1890 through 1920

2010: Paula A. Michaels, for Lamaze: An International History

“The NEH fellowships are among the most prestigious awards in the humanities, and it is noteworthy to have two UI faculty selected in the same year,” says CLAS Dean Steve Goddard. “Not only are they a reflection upon the individual faculty members and the quality of their research, but they elevate our reputation among peer institutions in the humanities as well.”

Balto, assistant professor of history and African American studies, and Stern, professor of philosophy, were among only 99 recipients nationwide for the 2020–21 award cycle, which included more than 1,000 applicants. Each will receive $60,000, allowing them to focus fully on their research projects.

For his current book project, Racial Framing: Blackfaced Criminals in Jim Crow America, Balto is researching a practice in which white people disguised themselves in blackface while committing crimes, something that was particularly common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“The fact that Professor Balto’s research project on crime, blackface, and minstrelsy was among the 8% of proposals selected for funding by the National Endowment for Humanities demonstrates the significance of his work,” says Venise Berry, department executive officer of African American studies. “He is an outstanding member of the faculty.”

Stern’s project focuses on the work of Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, author of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, or “Logical-Philosophical Treatise,” which is one of the most important and influential philosophical works of the 20th century. Stern will produce the first complete English translation of three drafts of Tractatus and its sources, including diaries Wittgenstein kept as a soldier during World War I.

“Professor Stern is one of the leading scholars in the world in his field, but the odds of receiving the award are so low, it’s just an impressive achievement,” says David Cunning, professor and department executive officer in the Department of Philosophy.

Reflecting on racial perceptions in America: Past and present

Balto came to the UI in 2018 from Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, where he was an assistant professor of history and founding director of the African American studies program.

A native Midwesterner, Balto received his undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin in 2005, and a few years later lived in Chicago for a period that proved to be brief but fruitful. While taking graduate courses at Roosevelt University, he became interested in the story of Fred Hampton, the Illinois Black Panther Party leader who was killed in a police raid in Chicago in 1969. Fred Hampton’s brother, Bill Hampton, spoke as a guest in one of Balto’s graduate classes.

“Hearing him talk about his brother sparked a keen interest for me,” Balto says.

At the same time, he observed patterns of racially disproportionate policing in the city, which he found troubling:

“Chicago is one of most segregated cities in the country,” he says. “Due to that segregation, a lot of people who live in affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods tend not to spend time in predominantly minority neighborhoods, so they don’t have a full appreciation of how different the police presence and activity look from one neighborhood to the next.”

After a semester at Roosevelt, Balto returned to the University of Wisconsin, where he earned a master’s degree in African American studies and a PhD in history. The subject of his dissertation led to the publication of his first book, Occupied Territory: Policing Black Chicago from Red Summer to Black Power.

Balto’s current project stems from that book—in particular from his study of an infamous 1919 riot in Chicago during which 38 people were killed in a violent scenario that Balto says is often misunderstood as solely “black against white.”

While reading a 600-page report on the riot published in 1922, Balto learned about some eye-opening incidents. In one, a group of Polish community members allegedly invaded a Lithuanian neighborhood and burned down buildings, doing so in blackface so their rivals would identify them to police as black. Upon further research, Balto discovered that such incidents were not confined to a particular region, and that perpetrators used the tactic in crimes ranging from bank robberies to murders. This not only skewed crime statistics against black people but instigated incidences of lynch mobs and other violence against them.

“There’s an ugly underbelly to this already-ugly practice of blackface that nobody talks about,” Balto says. “Throughout the Jim Crow era, black activists crusaded against this practice and the way white criminals were endangering black community members. I think we need to take their voices seriously even as we think about racism today.”

While Balto was immersed in his research, modern-day scandals came to the forefront in 2019 when political leaders admitted to having worn blackface at points in their past.

“What excites me about this project is that it gets us to new levels of how we think about what blackface has meant and how it reflects larger racial perceptions in America,” he says. “Any time a non-black person goes into blackface, it’s an act that draws from a deep well of racist caricature. Blackface has never been something that’s benign. This history gives us an even richer understanding of just how harmful it has the potential to be.”

Balto explores more recent racial themes in their historical context in the classroom at Iowa, such as in a fall 2019 undergraduate course titled Black Chicago: The Past, Present, and Future of an American Community. He also taught a recent undergraduate-graduate hybrid seminar focused on the works of African American essayist and novelist James Baldwin.

Balto says what he appreciates most about Iowa are his students and colleagues, the generosity of research funding that allows him to continually pursue new projects, and the receptiveness of department heads to new ideas for classes.

“During my brief time here, I have gotten to work with some of the most brilliant students I’ve ever had in my decade or so of teaching,” he says. “I also have some truly wonderful colleagues in both African American studies and history. In fact, one of the most striking things to me about winning this award is that I’m the fourth person to do so from the history department in the past 10 years, out of a total of eight from the entire UI community over that stretch. There’s just so many people in my departments and across campus doing exciting and important work that helps us make sense of the past, present, and maybe the future of our world.”

Bridging the personal and the philosophical

The London-born Stern graduated from the University of Oxford, earned a PhD from the University of California-Berkeley, and came to the UI in 1988, where he says he found a congenial and supportive department.

“I am fortunate to have such a splendid work environment, and I’m enormously grateful for it,” says Stern, who teaches undergraduate and graduate courses such as Principles of Reasoning, Minds and Machines, and Philosophy of Language. He recently co-developed a course called Language and its Social Roles, which explores social and political uses of language including lying, misleading, silencing, hate speech, and propaganda.

In 2016, in collaboration with two philosophy graduate students and the UI Libraries’ Digital Studio, Stern developed the University of Iowa Tractatus map, which presents the structure of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s book in the form of a subway-style map. The online tool enables users to explore the Tractatus’ structure, which consists of numbered sections and subsections.

In collaboration with graduate students and UI Libraries Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio, David Stern developed an interactive version of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophical work Tractatus in the form of a subway-style map, an online tool that simplifies navigation of the book’s sequences of statements.

For his NEH project, Stern will collaborate with two fellow Wittgenstein scholars on the first complete translation of the work and its German-language sources. The Tractatus, which was one of just two works Wittgenstein published during his lifetime, is among “a small group of dense and difficult” early 20th century modernist masterpieces, Stern says.

“Like Heidegger’s Being and Time and Joyce’s Ulysses, the Tractatus has been extraordinarily influential, not because there is general agreement on the nature of its contribution but because it has inspired such a wide range of powerful, but radically different interpretations,” Stern says. “A hundred years after Tractatus was written, there is no agreement about its approach to language and logic.”

Stern’s project will provide context that enables readers to follow the development of Wittgenstein’s thought as he turned his initial work on the book into a series of increasingly detailed drafts.

In his WWI diaries, Wittgenstein recorded philosophical material on the right-hand page and a more personal diary about his wartime experiences on the left.

“I’ll be putting left and right together, so to speak, for the first time,” Stern says. “The diary material has never been translated; it’s only been published in German.”

Wittgenstein enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian army despite a medical disqualification, facing grim realities that included a battle in the summer of 1916 in which three-quarters of his fellow soldiers died—an event that, Stern says, corresponds chronologically with the book “distinctly taking on a religious and mystical dynamic.”

“I think he expected to die, so it’s probably connected that there’s a radical change in the planning and writing,” Stern says. “There’s personal crisis recorded that has not been fully translated.”

During his career at Iowa, Stern has received several notable research awards from the university, each of which has had a career-changing impact.

In addition, he says the university has supported him more broadly by providing an environment in which collaborative work is facilitated and encouraged. The best example of that, he says, was the work of those involved in developing the Tractatus map.

“I have learned a great deal from conversations with colleagues and students on the second floor of EPB (the English-Philosophy Building) over the last 30 years, and the culture of my department has in many ways been just as valuable as those awards,” he says.