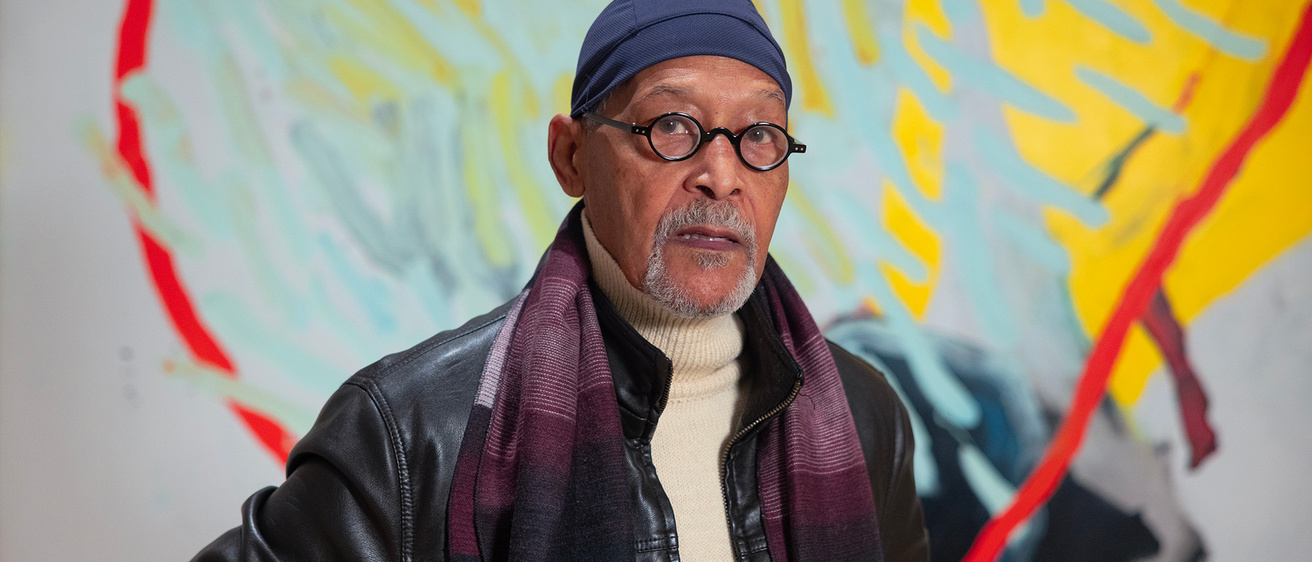

Iowa alumnus Oliver Lee Jackson’s paintings, sculptures, and prints have been exhibited in museums across the country — including the campus where he began to find his voice.

Story: Emily Nelson

Photography: John Emigh and Jason Smith

Published: May 3, 2023

For Oliver Lee Jackson, making art is far more than a career.

“It’s a calling, and I answer it the best I can,” Jackson says. “It has nothing to do with making a masterpiece or being successful. It’s demanded of me, and I yield to it.”

The painter, sculptor, and printmaker graduated with an MFA from the University of Iowa in 1963. Since then, Jackson has created a masterful, complex body of work that can be found in the collections of museums across the country, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Art Institute of Chicago, and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In honor of his transformative creative work and accomplishments as a public scholar, the University of Iowa will award Jackson an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters during its May 2023 commencement ceremonies.

Jackson says he is flattered by the honor. But he says he is even more moved by the inclusion of two of his works — Painting (4.78-I) and Painting (4.78-II) — in the Stanley Museum of Art’s inaugural exhibition upon reopening in 2022.

“I think this museum is quite wonderful,” Jackson says. “That the objects I made are in company with these wonderful objects, I really respond to that personally.”

“It was exciting to meet all these serious people, some of whom had already published. There was so much going on at that time, such as the Van Allen radiation belts and what they were doing in physics. It was an incredible mix of graduate-level people who were intensely involved in their disciplines. The exchanges were very intense and knowledgeable. It was really exciting.”

Jackson was born in St. Louis in 1935 and received a BFA from Illinois Wesleyan University in 1958. After serving in the U.S. Army, he enrolled at Iowa in the early 1960s where he studied with faculty such as Byron Burford and James Lechay.

Jackson says he found it interesting that Iowa didn’t separate the art historians from the makers. In the 1920s, studio art and art history were combined to form the School of Art and Art History. This innovative model became known as the “Iowa Idea” and would go on to become the standard for arts programs across the country.

“The art historians were very much wedded with the makers, but everyone understood the differences in what we were pursuing and devised a program that was thoughtful and useful for us studio people,” Jackson says. “There’s art history information that’s important to art historians, like iconography, and there’s information that’s important to studio arts, like composition and field.”

Jackson says the students in the School of Art and Art History also were close to graduate students in other disciplines, especially writing.

“It was exciting to meet all these serious people, some of whom had already published,” Jackson says. “There was so much going on at that time, such as the Van Allen radiation belts and what they were doing in physics. It was an incredible mix of graduate-level people who were intensely involved in their disciplines. The exchanges were very intense and knowledgeable. It was really exciting.”

During a trip back to the University of Iowa in February 2023 for a lecture and residency, Jackson recalled his time in Iowa City as important for gaining a better understanding of his use of materials and assessing his intentions during the making process.

But, he says, the work of truly finding his voice and confidence in his work continued well after he left Iowa.

“I was still working things out when I was here,” Jackson says. “I had the skills; I had an understanding. But my vision—it took a while for me to understand what I was doing and not copying anyone, and to become confident about each mark I was making and that I didn’t need anybody over my shoulder because I was my own best and worst critic. And that all took a minute; it wasn’t immediate at all.”

After graduating with an MFA, Jackson returned to St. Louis. There, he worked extensively with community-based arts groups, including the People’s Art Center and Program Uhuru, which he started in order to offer low-income youths a constructive means of developing dialogue through arts programs. Jackson also became involved with the Black Artists Group, which included musicians, theater artists, dancers, and visual artists devoted to raising Black consciousness, battling social injustice, and exploring the far reaches of experimental performance.

“Art is a calling, and I answer it the best I can,” Oliver Lee Jackson says. “It has nothing to do with making a masterpiece or being successful. It’s demanded of me, and I yield to it.”

Jackson was nominated for the honorary degree by Sara Sanders, dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Randall Griffey, head curator of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; Laurel Farrin, professor in the School of Art and Art History; T.J. Dedeaux-Norris, associate professor in the School of Art and Art History; and Harry Cooper, senior curator of the Modern & Contemporary Art National Gallery of Art.

Support for younger artists was a common theme in the nomination letters.

“Mr. Jackson’s commitment to mentorship within the art world toward younger careered artists is a labor of love all on its own,” Dedeaux-Norris writes in his nomination letter. “I have found this service and engagement to be rare for well-established artists, much less an artist with a 60-year career.”

During a trip back to the University of Iowa in February 2023 for a lecture and residency, Jackson recalled his time in Iowa City as important for gaining a better understanding of his use of materials and assessing his intentions during the making process.

Over the years, Jackson has taught and lectured in art, philosophy, and Pan-African humanities, as well as served as an artist-in-residence or visiting artist at numerous institutions.

However, Jackson says what he does is train, not teach.

“They make themselves artists; I don’t,” Jackson says. “I don’t think you should make any student under you a follower of what you do, but instead bring them to the deepest understanding, without romanticism, of the intimacy that you need to feel very, very comfortable with your materials—whether that is paint, bronze, steel. I want them to be able to assess their intention and be critical in a powerful way of themselves and not stumble over not understanding materials or techniques.”

Jackson’s practice is expansive, encompassing painting, installation, and film, among other media, and his esteem continues to grow as he maintains a challenging practice into his ninth decade of life.

“In painting after painting and in sculptures, prints, and drawings, too, Jackson has broken new ground: combining figuration and abstraction in innovative ways, deploying color and space like no painter since Joan Mitchell, unleashing stunning, virtuoso improvisations inspired by jazz, and exulting in the joy of making,” says Lauren Lessing, director of the Stanley Museum of Art.

Lessing says Iowa’s museum made acquiring work by important alumni a central goal—and a diptych of Jackson’s now offers visitors a master class in composition.

“Like anyone who follows contemporary art, I’d known of Mr. Jackson’s work for years. He’s a beautiful, exciting, innovative painter whose deft handling of his materials is just so compelling,” Lessing says. “I’m proud to work at the university where he began his career.”