Thanks to Ian Mallory’s investigation, which involved untangling hundreds of documents and obtaining a crucial DNA test, a California man who had been falsely imprisoned and involuntarily hospitalized for saying he was who he said he was regained his true identity.

Story: Emily Nelson

Photography: Tim Schoon

Illustrations: Kendra Wilson

Published: March 3, 2025

When two people share the same name, giving them nicknames is one method for keeping straight who’s who.

This method helped Ian Mallory, a detective for the University of Iowa Police Department, after a February 2023 phone call with a William Woods, who at the time was a University of Iowa Health Care employee living in Hartland, Wisconsin. His shorthand reference became Wisconsin Bill.

Wisconsin Bill was having issues with a man in California. The man on the West Coast — whom Mallory would come to think of as California Bill — was saying he was William Woods, and he made numerous complaints about Wisconsin Bill. This had been going on for years, and Wisconsin Bill wanted it to stop, once and for all.

“I sort of felt bad for Wisconsin Bill. He had so many identity theft protections in place, and it sounded like a pain,” Mallory says. “I thought the guy in California was probably a professional con man. I told Wisconsin Bill, ‘I want to make this right for you. I want to do what I can to get this rectified for you.’”

Mallory knew that multiple law enforcement agencies had dismissed California Bill and that a state court already had ruled that California Bill was not William Donald Woods. It would have been easy to follow their lead.

And if it wasn’t for what Wisconsin Bill said next, Mallory admits he may not have dug as deep as he did.

“He told me, ‘You’re not going to be able to do anything,’” Mallory says. “I’m sure he thought that I was just a flashlight-carrying, keychain-jingling security guard. I think a lot of people assume that about campus police.

“But that comment really made me want to find the truth once and for all.”

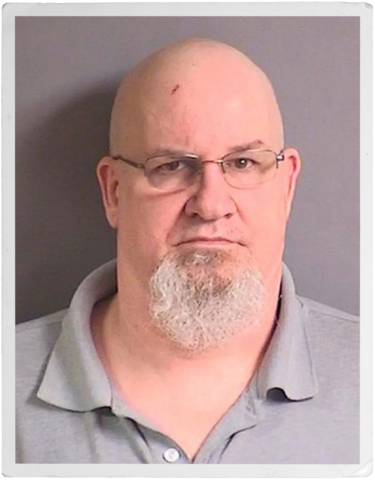

Discovering the truth was not the outcome that Wisconsin Bill — whose real name turned out to be Matthew David Keirans — ever wanted.

But thanks to Mallory’s investigation, one that involved untangling hundreds of police and government documents and obtaining a DNA test, Keirans’ three-decades-long identity theft scheme came crashing down. A scheme that fooled numerous employers, police officers, and courts — even a wife and son. And, tragically, a scheme that had led to the false imprisonment and involuntary hospitalization of California Bill — the real William Woods — for insisting he was who he said he was.

“California Bill has been victimized and revictimized and revictimized,” Mallory says. “He had the system fail him on so many levels. It’s no secret that Bill has lived on the wrong side of the law; he’s not a saint. But man, he was really taken for a ride on this.”

“I think it’s safe to say if it hadn’t been for Ian’s work on this, the real Bill Woods would still be suffering. And we would still have an employee who was not who he said he was.”

The stranger-than-fiction case started more than 30 years earlier, when Matthew David Keirans and William Donald Woods worked together at a hot dog cart in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1988.

Soon after, Keirans started using the name William Woods — sometimes listing his middle name with the initial “D,” other times “Donald,” and later “David.” He used Woods’ name in every aspect of his life, paying taxes and obtaining a social security number, birth certificate, driver’s licenses, insurance, titles, loans, credit, and employment. In 1994, he got married under Woods’ name and had a child, whose last name is also Woods.

In 2013, Keirans applied for and obtained a job at University of Iowa Health Care. He previously worked at Kohl’s and the Kentucky Department of Education, and in various contractor positions. He provided a driver’s license and social security card in Woods’ name. A background check revealed no anomalies.

After being a weekly commuter to Iowa City for a couple of years, Keirans was given permission to work remotely from where he and his family lived outside Milwaukee.

Mallory first heard of Keirans — or as he was known then, William David Woods — in January 2023.

A man in California who identified himself as William Donald Woods called UI Health Care to report that one of their employees had stolen his identity. The report was turned over to the UI Police Department to investigate.

This was not the first time that Woods had contacted officials claiming that Keirans had stolen his identity. The first time the two clashed, Woods ended up in jail and confined to a mental hospital.

• • • • •

In 2019, after checking his credit report and discovering several open credit cards in his name, Woods, who was homeless at the time, walked into a branch of a national bank in California with the intention of closing the credit cards and clearing his credit. He gave the bank his social security card and state of California identification card.

Woods, however, was unable to correctly answer a series of security questions. The bank teller contacted Keirans, whose phone number was listed on the account. Keirans correctly answered the security questions, provided phony identification documents in Woods’ name, and said he never gave anyone in California permission to access his bank accounts.

The bank then called the Los Angeles Police Department, and Woods was arrested, charged with two felonies, and held without bail at the Los Angeles County Jail.

Throughout the proceedings, Woods continued to insist that he was who he said he was. A California state court judge ordered Woods to a state hospital for a mental competency evaluation to determine whether he could stand trial and ordered that he be held in a California mental hospital and given psychotropic medication.

Woods pleaded “no contest” to the two felony charges in exchange for a “time-served” sentence and was released from custody.

Woods ultimately spent 428 days in jail and 147 days in the mental hospital.

Despite that, Woods continued to make numerous attempts to try to regain his identity, including contacting police in Hartland, Wisconsin, where Keirans was living. But each time, Keirans successfully convinced investigating officers that Woods was the imposter who was trying to steal Keirans’ identity.

That’s when Woods discovered that Keirans was working for the university and made a call that brought Mallory into the twisting and turning saga.

• • • • •

“I applied to all of the best, most forward-thinking, top-of-the-class police departments. I had several job offers, and I picked this department over all of them because I saw the facilities, equipment, resources, and the people, and I thought that this is a place I want to work. I want to immerse myself in this kind of environment.”

Mallory says he always wanted to go into law enforcement — although his journey to the profession took a few detours.

“I come from a family in public service,” Mallory says. “My dad was a physician, and I grew up seeing him serving our local small town. Public service is ingrained in our DNA.”

When asked why he wanted to become a police officer, Mallory doesn’t hesitate with his answer.

“I want to be the voice for people who don’t have a voice,” Mallory says. “I want to be an advocate for people who don’t know how to resolve something.”

Mallory went to Hawkeye Community College to get a degree in police science. Unfortunately, after graduation, he couldn’t initially pass the physical agility test required to become a police officer. Instead, he went into communications engineering.

“It was, and still is, my hobby, and I was able to make it my career for many years,” Mallory says. “But I always secretly wanted to do police work.”

After his father died of cancer in 2015, Mallory decided it was time to chase his dream. He made some lifestyle changes and passed his tests to become a police officer.

“I applied to all of the best, most forward-thinking, top-of-the-class police departments,” Mallory says. “I had several job offers, and I picked this department over all of them because I saw the facilities, equipment, resources, and the people, and I thought that this is a place I want to work. I want to immerse myself in this kind of environment.”

Mallory’s colleagues say he was the perfect investigator to handle this complex case.

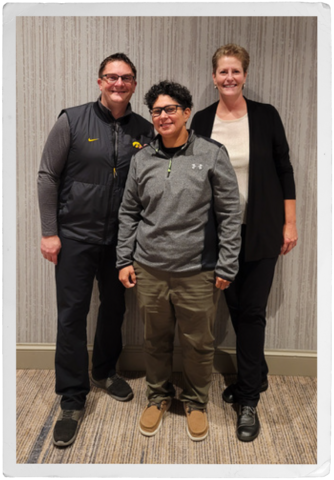

“I don't think it was just one thing; it was several things,” says Lucy Wiederholt, chief of the University of Iowa Police Department. “He’s very smart and he listens to his instincts. When something doesn’t feel right, he follows through on it. Sometimes if you can’t put that final piece together, even if it’s nagging at you, you might be tempted to let it go. But Ian isn’t that kind of guy.”

Colleagues also say Mallory can’t resist a good challenge. It’s a joke around the office that if you have a tough case, you just loudly exclaim “No one is going to be able to figure this out” when Mallory is nearby.

“They all know that is a challenge-accepted moment for me,” Mallory says, laughing.

Ian Mallory, a detective with the UI Police Department, worked through hundreds of documents from several states as he investigated the background and criminal history of "William Woods."

Diving into the documents

Mallory says he initially did not know what to think about Woods’ and Keirans’ seemingly fantastic claims.

“Both were saying, ‘I’m the real guy and the other guy is an imposter,’” Mallory says.

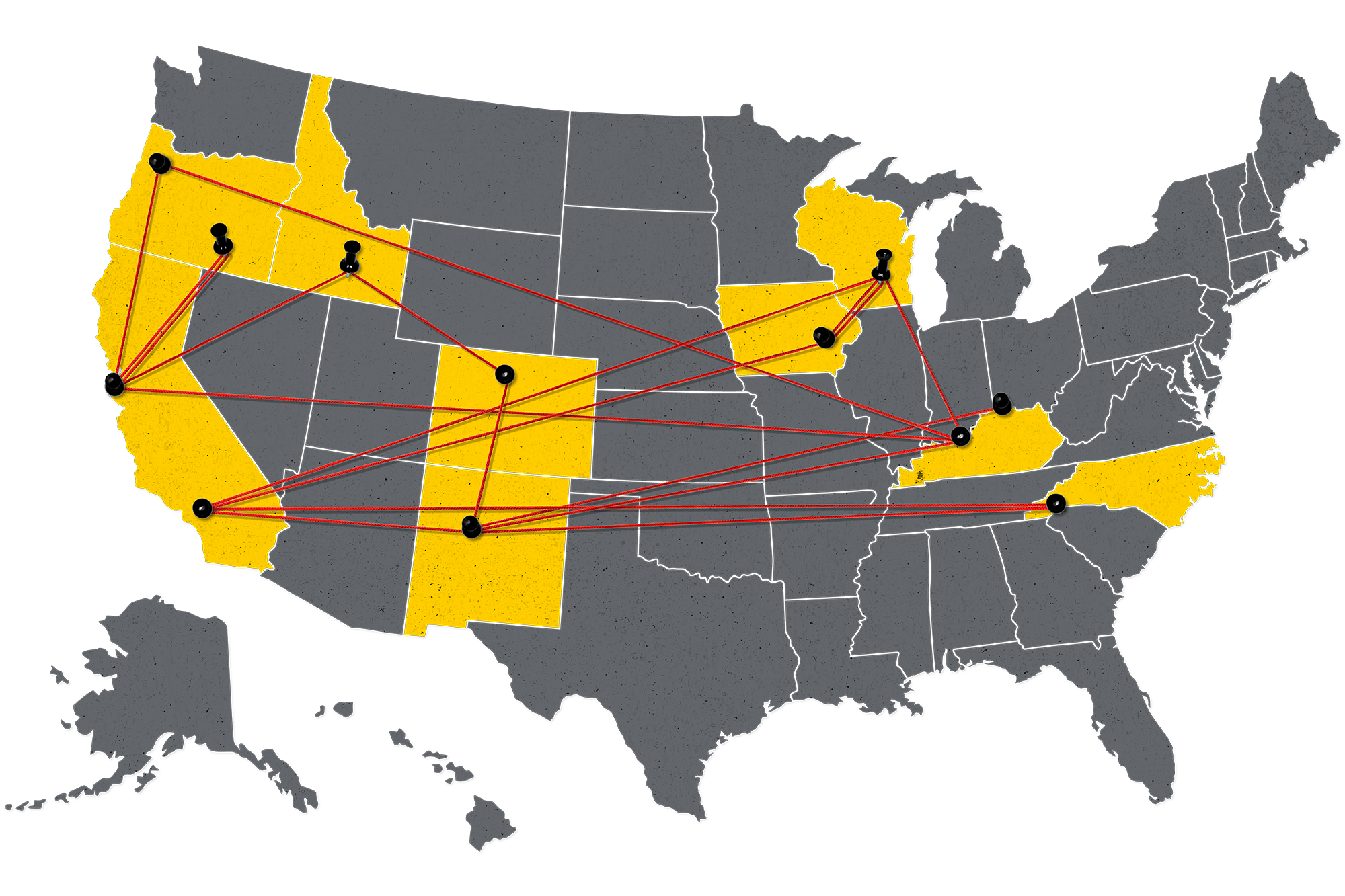

Mallory started his investigation by looking at any records he could get his hands on. There were a lot — and they came from all over the country.

He combed through hundreds of police and government documents from Wisconsin, California, Idaho, Colorado, Oregon, Kentucky, and Iowa to investigate the background and criminal history of “William Woods.”

One stood out: a 1995 North Carolina forgery case.

“This became the first data point where we could differentiate life events between the two men,” Mallory says. “The fingerprints, photo, and identity all matched California Bill.”

Getting his hands on such documents wasn’t always easy. For example, not every department has mug shots from back then digitized.

“I once asked if they could look up the Polaroid from a 1995 case, and the woman on the phone asked what a Polaroid was,” Mallory says, laughing. “I asked if I could speak to the oldest person there.”

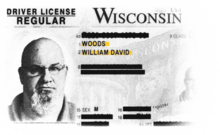

Mallory also examined the two men’s birth certificates. Woods’ birth certificate, which he sent Mallory from California, was validated by the Kentucky Bureau of Vital Statistics. Mallory then asked Keirans for his birth certificate, which Keirans provided. The Kentucky office verified this document as well, noting that it was a reprint record from June 13, 2012.

Both birth certificates had the name “William Donald Woods” on it. However, it appeared that soon after getting the birth certificate in 2012, Keirans started using the name “William David Woods” — David being his real middle name.

“That really was the moment that I knew there was something wrong with Wisconsin Bill’s story,” Mallory says.

Mallory would later discover that Keirans was ticketed on June 12, 2012, in Wisconsin for driving without a license. Keirans researched Woods’ family history on a genealogy website and used that information to obtain a copy of the birth certificate from the state of Kentucky the next day. On July 16, 2012, he got a Wisconsin driver’s license, although in the name “William David Woods.”

“That was the creation of ‘William David Woods’ instead of ‘William Donald Woods,’” Mallory says.

The name discrepancy on Keirans’ documents didn’t go unnoticed by LAPD in 2019, but Keirans explained that while he sometimes went by the middle name of David, his real middle name was Donald.

During his investigation, Ian Mallory pored over hundreds of documents related to William Woods from several states, spanning both coasts and dotting many regions on the map.

Breakthrough in the Bluegrass State

Mallory’s next move provided the first big breakthrough in the case. He tracked down the parents listed on the birth certificate that both men claimed was theirs. Woods’ mother had died, but Mallory found the father living in Kentucky.

“He is a sweet old fella, and we had some nice long conversations over the phone about everything and anything,” Mallory says. “He told me he hadn’t seen his son in years but that he lived in California and talked to him regularly.

“I admit I did wonder if California Bill could be so low as to talk to this guy and pretend to be his son.”

Woods consented to a DNA swab, which the Santa Monica, California, Police Department helped obtain. They also took a new photo of Woods. The Covington, Kentucky, Police Department then visited Woods’ father and showed him several photos. He picked out Woods as his son. The officer also took a DNA swab from the father. The swabs were sent to the Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation.

On June 19, 2023, Mallory received the results: William Woods in California was the son of the man in Kentucky.

“This was momentous,” Mallory says. “But then the big question was, ‘Who is the William Woods working for the University of Iowa?’”

• • • • •

Mallory got his answer a couple of days later, thanks to Tina Salisbury, an analyst in the Iowa Division of Intelligence.

“In that huge jumble of records we had, she noticed this one number,” says Travis Tyrrell, lieutenant, Investigations and Professional Standards for UIPD. “I never would have caught it; most people wouldn’t.”

Every person’s criminal history has an FBI number attached to it. When a person’s criminal history is searched, everything with that number pops up. Hidden within the hundreds of documents for William Woods, there was a note regarding an additional record number.

Looking up that specific record number resulted in finding a 1987 forgery case in Louisville, Kentucky, and a 1988 criminal trespass case in Albuquerque. These cases were linked to a Matthew David Keirans with a birth date and social security number different from Woods’.

Mallory requested the mug shot and fingerprint from Louisville.

“I’m not a fingerprint expert, but I had been looking at California Bill’s fingerprint for so long that I could tell immediately it wasn’t his,” Mallory says. “It was the same for the Albuquerque case.”

Though it was not initially clear why or when Keirans’ and Woods’ FBI records were merged under the name William Donald Woods, the criminal history did in fact have two different identities with exact names, dates of birth, and social security numbers.

“That was the biggest challenge in this case; any time I researched any of the two names, I would get one resulting record with two lives merged together,” Mallory says. “Your FBI number is given to you based off your fingerprints. So why would they merge two criminal histories and two records if every person's fingerprints are unique? In early 2023, I didn’t have a concrete answer.”

But it did mean that Mallory finally had a new name to research.

Who is Matthew?

Matthew David Keirans was born in 1966 and raised in California by adoptive parents, both of whom have since died. Keirans left home at age 16 or 17, never graduated from high school, and picked up arrest records in California, Kentucky, and New Mexico.

There are no records of Keirans using his own name, date of birth, or social security number after 1988, when he worked with Woods at a hot dog cart in Albuquerque.

In 1990, Keirans obtained a Colorado driver’s license using the name “William D. Woods.” The next year, he committed multiple crimes in other states, including Idaho, California, and Oregon. In 1993, a William Donald Woods was arrested for theft of a motor vehicle in Oregon — an offense that had not been linked to Keirans until 2023, when Mallory obtained the original fingerprint card and resubmitted it to the FBI. Those fingerprints matched Keirans’ — and marked another break in the case that conclusively put him in that area.

A year later, Keirans married and had a child and there were no further police records — other than traffic violations — matching him.

Mallory says he doesn’t know if anyone will ever know why Keirans stole Woods’ identity, but he says he suspects he knows why Keirans used it as long as he did.

“He met a woman, fell in love, and had a baby. And then he was stuck with this identity,” Mallory says. “I think his motivation after that was family.”

• • • • •

According to a 2021 Bureau of Justice Statistics report, 9% of the U.S. population had experienced identity theft in the past year, and 1 in 5 people had experienced it in their lifetime. That included 4% of people having their credit card misused, 3% having their bank account misused, and 1% having their personal information misused for fraudulent purposes, such as getting medical care or applying for a job or government benefits.

It's not uncommon for the University of Iowa Police Department to investigate stolen credit cards. They also occasionally see cases of people falsifying résumés to get a job, using a false identity for health insurance purposes, or even misrepresenting themselves as a subject matter expert for financial gain.

But the type of identity theft and identity fraud that Mallory was investigating is extremely rare.

“I don’t think you could replicate this today,” says Mark Bullock, assistant vice president of Campus Safety at Iowa. “We have all these different systems that monitor people’s financials. I don’t even know how you would start. I think one of the only reasons this worked for so long was because the real William Woods was off the radar and not functioning in society like other people who had bank accounts and credit cards that they regularly use and check.”

Mallory says he sometimes found himself having to convince authorities in other jurisdictions to help him dig up old documents.

“Very few people have seen something comparable to this,” Mallory says. “I found that by saying they had the opportunity to help break a 30-year-old identity theft case often motivated people to help me.”

Sometimes, just getting people to talk to him in the first place could be difficult.

“The first hurdle was sometimes just convincing them I am a real police officer,” Mallory says. “I stopped saying I worked for the University of Iowa Police Department and just said I was a police officer in Iowa.”

Unfortunately, Mallory and his colleagues say, it’s common for people not to realize that a university campus can have a “real” police department. Bullock says while there can be varying levels of authority, experience, and expertise in campus policing, UIPD officers have the same training and access to the same resources any department would have — and often more time to dedicate to detailed investigations than do larger, municipal departments.

“We sometimes take for granted that we have a lot of things that other departments — sometimes even those that are much bigger than us — don’t have,” Bullock says. “We’re fully staffed 24/7 and provide a lot of different services. We have canines, we have bomb techs, we have detectives, we have a drug task force officer, and we have a digital forensics lab that we share with our partners within Johnson County. We have a lot of resources that other departments would love to have, and we do our best to use that to assist law enforcement agencies across the state.”

A sophisticated, multilayered approach to public safety

Over the past few decades, campus safety services have evolved significantly in response to increasing concerns about student safety and high-profile incidents — and the University of Iowa is no exception.

Today at UI, sworn police officers and certified security officers are just one layer of a multi-faceted approach to safety. The eight-department Campus Safety organization includes the UI Police Department, Security Services, Emergency Management, Threat Assessment, Clery Compliance, Security Engineering Services, Emergency Communications, and Fire Safety.

There are common myths about the UI Police Department — we present the truths.

• • • • •

Throughout the investigation, Keirans contacted Mallory by phone and email every couple of days to ask for the latest developments in the case.

“One of the cardinal rules of investigations is to not talk to subjects of your investigation until you’re ready and you hopefully have information,” Mallory says. “I wasn’t ready to talk to him, so I just kept telling him thanks for checking in, but I was still working.”

Emails later recovered from Keirans’ laptop showed he also was actively communicating with authorities in Los Angeles to try to get Woods reincarcerated while Mallory’s investigation was underway.

“He was clearly trying to get information about the guy who could wreck his plan,” Mallory says.

Mallory says normally he and his colleagues would take months to build as solid a case as possible before arresting Keirans. However, because of Keirans’ position as a systems analyst in the university’s Health Care Information Systems, there was concern about waiting too long. While there was no evidence that the security of any systems or data was compromised, he was part of a team that administered servers for enterprise software.

First, Mallory and his colleagues had to decide on which charges to arrest Keirans. Because Keirans didn’t steal Woods’ identity in Iowa, the state couldn’t charge him with it.

Several officials at the federal level and in multiple states told Mallory they didn’t think they had jurisdiction to charge Keirans with anything.

“I think people shied away from this case because no one had seen anything like it,” Mallory says.

Finally, it was decided Keirans would be arrested for providing false information to police during a traffic stop earlier in 2023 in North Liberty, Iowa, as well as presenting William Woods’ birth certificate to Mallory as his own. That would give them time to investigate further while also keeping him away from the university’s IT servers or from disappearing entirely.

On Friday, July 15, 2023, Mallory and his team learned that Keirans would be on campus the following Monday. Over the weekend, Mallory secured search warrants for Keirans’ DNA and fingerprints while the Wisconsin Division of Criminal Investigation secured search warrants for Keirans’ home and car.

“They were awesome partners,” Mallory says. “I was fortunate to have had many excellent people at law enforcement departments across the country help me with this case. And my colleagues at UIPD were always there to bounce ideas off of or to provide guidance when I was stuck.

“And then there came a point when everything was breaking, and it was all hands on deck. Everybody had a role to fill.”

All the warrants were obtained under the name “John Doe.”

“This meant he would have to fight identity and prove who he was,” Mallory says.

The original plan called for officers in Wisconsin to begin surveillance Sunday. They would follow Keirans to the Iowa border, at which point Iowa officers would take over.

However, Wisconsin officers discovered Keirans was already gone. Fortunately, a search of hotels in the Iowa City area located him, confirming he had already returned to the area to report to work.

On Monday, July 17, 2023, Keirans left his hotel and went to work, where investigators kept careful watch. At 3:30 p.m., the “go” sign was given and Keirans was arrested.

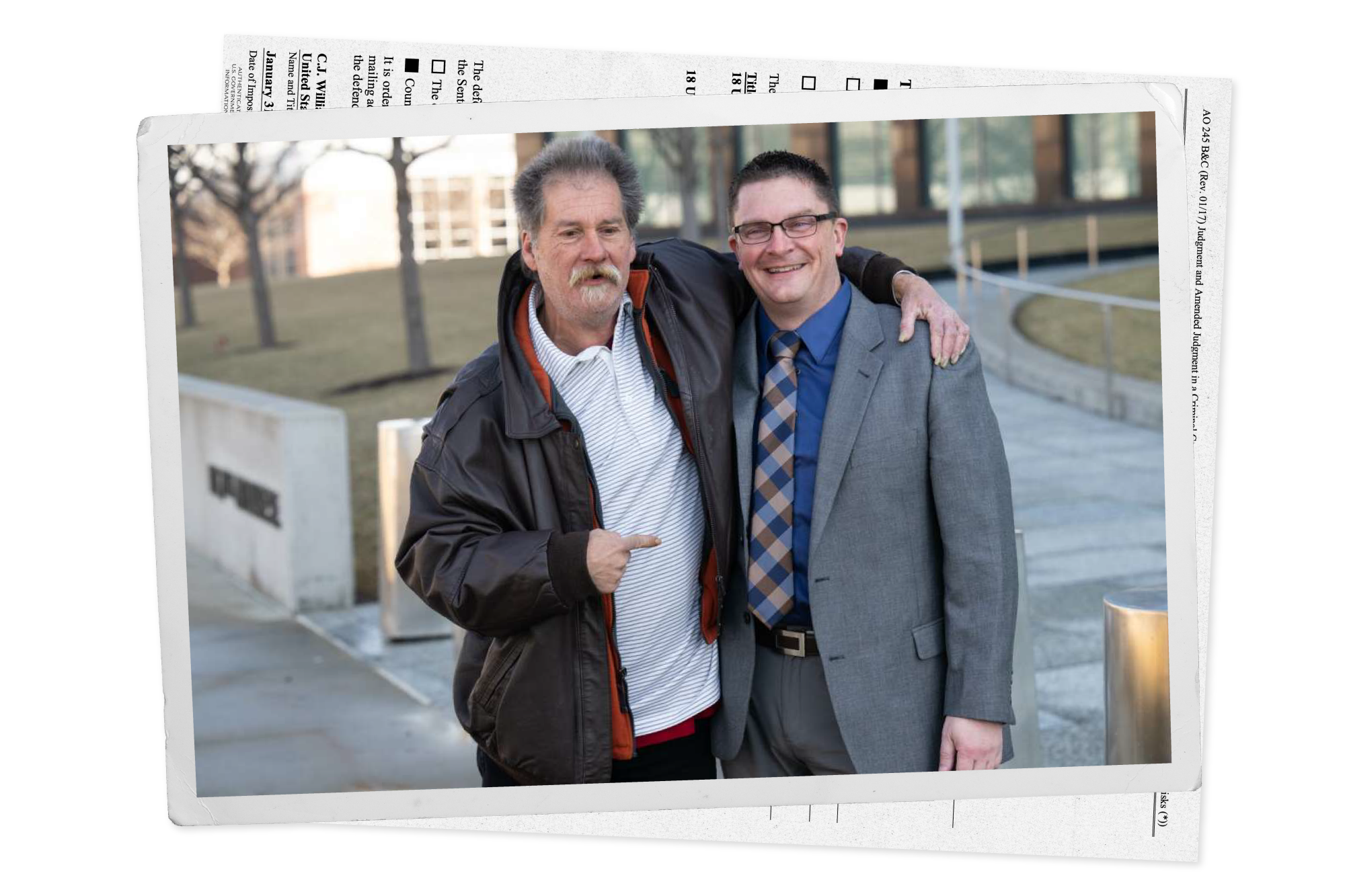

William Woods points at UIPD Det. Ian Mallory outside the courthouse after Matthew Keirans' sentencing Jan. 31, 2025, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. “I was sent to jail for nothing; for being myself,” Woods told reporters after the sentencing. “The truth is important, and now the truth is known.”

At the University of Iowa Police Department, Keirans was photographed and fingerprinted.

“I couldn’t wait to see that right index finger,” Mallory says. “The fingerprint was a dead match for what I had been looking at.”

Mallory and Keirans then sat down for what would be a six-hour interview.

“We danced around for hours,” Mallory says. “He knows that I know. I know that he knows that I know. I just wanted him to say it, to confess.”

Finally, Mallory brought up the man in Kentucky who was listed as the father on the birth certificate for William Woods. Keirans had at one point told Mallory that his father was dead. Mallory knew there was no way Keirans would be able to continue the interview without addressing the topic of his father.

“I found your dad, who’s alive,” Mallory said in the interview.

“I thought he died,” Keirans replied.

When Mallory asked Keirans what his dad’s name was, he replied “John.” A second later, he replied with the correct name for Woods’ father.

Keirans had mixed up the names of his own father and Woods’ father.

Mallory then confronted Keirans with the DNA evidence that conclusively revealed that William Woods in California is the son of the man in Kentucky.

“I said, ‘They are related. You are not. The father on the birth certificate you gave me has seen photos. He doesn’t know who you are. Who are you?’” Mallory asked.

“My life is over, isn’t it?” Keirans replied. And, soon after, “My name is Matthew Keirans.”

“He said, ‘Cool. I told you so. No one believed me.’”

Mallory calls Keirans a “professional manipulator.”

“He was trying to play me in that interview,” Mallory says. “For years, he was playing everyone. He at one point said to me, ‘You know who could catch me? I could catch me.’”

Early in the interview, Keirans insisted that Woods was “crazy” and “should be locked up.”

“He later told me that he tried to get California Bill locked up,” Mallory says.

Keirans told Mallory that he had a chaotic upbringing and a father who was an alcoholic who abused him. However, people who knew Keirans when he was young say he had a nice, normal childhood, went to a private school, and had just about everything he wanted. Mallory was told Keirans even owned one of the first Apple computers on the market.

Even after admitting his real name during the initial interview after his arrest, Keirans gave his fake name during booking.

“For 30 years he had been rattling off this fake name,” Mallory says.

During an interview the next day, Keirans asked Mallory to call him “Matt.”

“He said he might as well get used to it,” Mallory says. “He told me several times that he felt relieved that it was finally over.”

• • • • •

Soon after Keirans was taken into custody, Mallory called Woods.

“He said, ‘Cool. I told you so. No one believed me,’” Mallory says.

While Keirans’ charges made their way through the court system, Mallory contacted the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office to help Woods get his sentence vacated now that it was clear he was the real victim in the case. However, Mallory was told they felt there was no problem with the conviction.

A day after Keirans pleaded guilty to federal charges in April 2024, a reporter contacted the Los Angeles Police Department and Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office. Two days after that, a motion to vacate Woods’ sentence was filed.

On April 11, 2024, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge vacated the conviction, and then- Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón offered a public apology.

“I’m happy, because I knew I was innocent anyway,” Woods told the Los Angeles Times. “I knew I was innocent.”

“The defendant weaponized the criminal justice system to achieve his goals. What the victim was deprived of was priceless — his freedom.”

Keirans is sentenced; Woods is cleared

UI Health Care fired Keirans the day after he was arrested. An investigation by outside cybersecurity consultants found no evidence that the security of any systems or data was compromised.

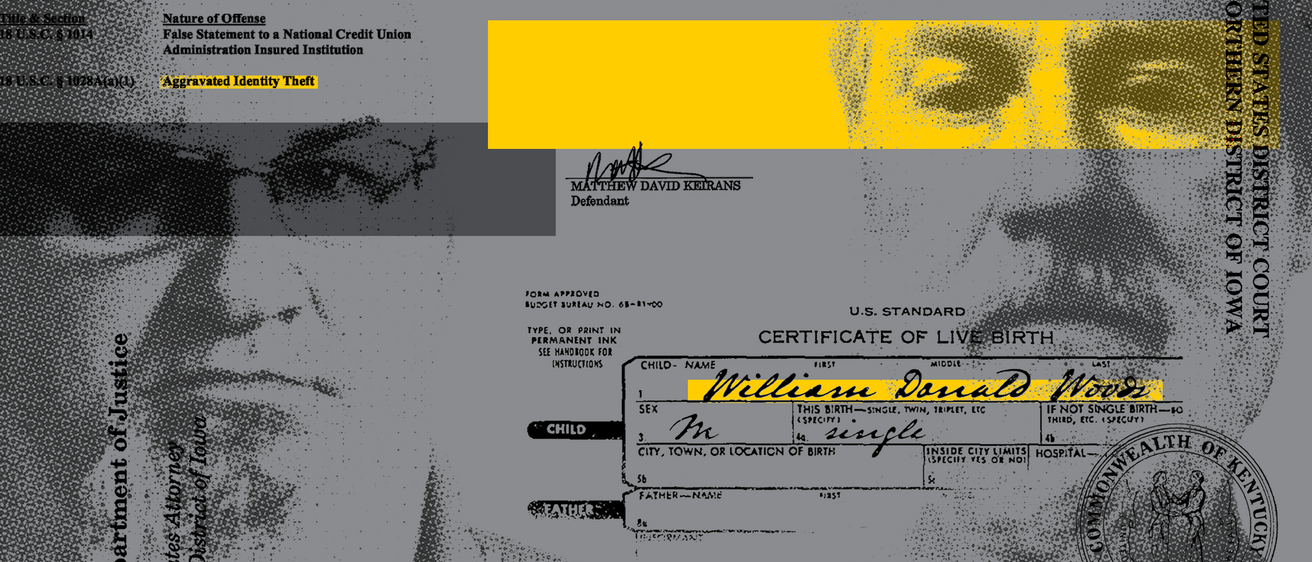

The next month, August 2023, Keirans pleaded guilty in Johnson County to unlawful use of a birth certificate. He was then transferred to Bremer County, Iowa, on state charges filed by Special Investigator Dawn Blahnik of the Iowa Insurance Fraud Bureau. Blahnik determined Keirans had obtained various insurance policies in Iowa under Woods’ name. While in custody, Assistant U.S. Attorney Tim Vavricek picked up the case and a grand jury federally indicted Keirans for two felony charges, one count of making a false statement to a national credit union administration–insured institution and one count of aggravated identity theft. These charges related to Keirans obtaining eight loans between August 2016 and May 2022 totaling more than $200,000 from two credit unions in the Northern District of Iowa using Woods’ name.

Keirans pleaded guilty to the federal charges on April 1, 2024, and, on Jan. 31, 2025, was sentenced to 12 years in federal prison. He also was ordered to pay a fine of $10,000 and pay $10,000 in attorney's fees to his federal public defender. He already has paid $6,190 in court-ordered restitution to Woods. Keirans must also serve a five-year term of supervised release after the prison term.

Chief Judge C.J. Williams, who presided over the sentencing of what he called a “weird, unique case,” lamented that Keirans eroded trust in the criminal justice system.

He also delivered some scathing remarks about Keirans, calling him “callous.”

“The defendant weaponized the criminal justice system to achieve his goals,” Williams says. “What the victim was deprived of was priceless — his freedom.”

Woods, who now lives in New Mexico and works as a landscaper, traveled to Iowa for the sentencing.

“I was sent to jail for nothing; for being myself,” Woods told reporters after the sentencing. “The truth is important, and now the truth is known.”

• • • • •

Keirans’ prison sentence is not necessarily this story’s final chapter. Keirans’ DNA is waiting to be processed; it’s possible that it may turn up in other crimes. There are practical questions, too: Is the marriage license for Keirans and his wife null and void? What does his son do about his last name? Keirans paid taxes under Woods’ name for decades — who can collect on the associated social security?

These questions aren’t for Mallory to answer. He is no longer actively working the case, but he is receiving praise for the work he did. In 2024, the U.S. Attorney’s Office, which prosecuted the case, presented Mallory with its Law Enforcement Victim Service Award.

From Vavricek's nomination letter:

“Detective Mallory did not dismiss Woods’ seemingly fantastic claims out of hand and instead spent the ensuing months unraveling Keirans’ identity theft scheme. Through his open-mindedness, patience, and diligence, Detective Mallory was able to successfully unravel a sophisticated, three-decades-old fraud that had successfully fooled other police officers, courts, banks, and government officials. Although the reporting victim had felony convictions, was homeless, and had been recently found incompetent by a court, Detective Mallory took the time to listen to him and did not fail to pursue verifiable facts simply because of possible credibility concerns of the victim. Through his persistence, Detective Mallory not only helped to protect William Woods from further victimization by Keirans, but he also protected the University of Iowa Hospital’s [sic] information systems from being guarded by a prolific identity thief.”

Bullock says Mallory’s goal to always be a voice for the voiceless is evident in this case.

“I think Ian is a natural advocate for the underdog,” Bullock says. “Bill Woods was sent to prison for being himself. That’s a heck of an underdog.”

There’s no longer a need for the nicknames California Bill and Wisconsin Bill. William Woods’ name has been cleared — literally — thanks to Mallory’s relentless digging.

“I think it’s safe to say if it hadn’t been for Ian’s work on this, the real Bill Woods would still be suffering,” Bullock says. “And we would still have an employee who was not who he said he was.”

As for Mallory, he says he is honored to have played a role in helping give Woods back his name.

And he says he hopes to never see another case like this.

“No matter whether you have $6,000 or $6 to your name, you still have your name,” Mallory says. “William Woods didn’t even have that because Matthew Keirans took it. It’s one of the most egregious things one person can do to another.”

The timeline of events

Matthew David Keirans is born in California.

January 1966William Donald Woods is born in Kentucky.

May 1968Keirans is arrested under his own name in California, Kentucky, and New Mexico.

1985–88Keirans and Woods work together at a hot dog cart in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

1988Keirans obtains a Colorado driver’s license under “William D. Woods.”

1990Keirans is arrested under Woods’ name in Idaho, California, and Oregon.

1991–93Keirans gets married and has a child under the name Woods.

1994Keirans holds multiple jobs under the name Woods, including at Kohl’s, the Kentucky Department of Education, and various contractor positions.

1997–2012Keirans requests and receives the Kentucky birth certificate for William Donald Woods and gets a Wisconsin driver’s license under the name “William David Woods.”

2012Keirans is hired as William David Woods by University of Iowa Health Care.

2013William Woods tells a bank in California that someone was using his identity, and he wished to close his accounts at the bank. Because he could not answer the security questions, the bank called the Los Angeles Police Department, which arrested Wood

2019A California state court judge finds Woods not mentally competent to stand trial and orders him to be held in a California mental hospital and to receive psychotropic medication. In March 2021, Woods pleads no contest to the two felony charges in

2019-21William Woods calls human resources at UI Health Care to report an employee using his identity.

Jan. 13, 2023The case is turned over to Ian Mallory, then a patrol officer, who begins his investigation. Mallory was assigned to the investigations division as a detective in March 2023.

Jan. 31, 2023DNA verifies that William Woods is who he says he is.

June 19, 2023Iowa Division of Intelligence identifies FBI record that shows that the UI Health Care employee is Matthew David Keirans.

June 22, 2023Keirans is arrested in Iowa.

July 17, 2023Keirans pleads guilty in Johnson County, Iowa, to unlawful use of a birth certificate.

Aug. 14, 2023Keirans is indicted on federal charges of one count of false statement to a national credit union administration–insured institution and one count of aggravated identity theft.

November 2023Keirans pleads guilty to federal charges.

April 1, 2024William Woods’ criminal convictions related to Keirans are vacated.

April 11, 2024Keirans is sentenced to 12 years in federal prison.

Jan. 31, 2025