Working at forefront of space science

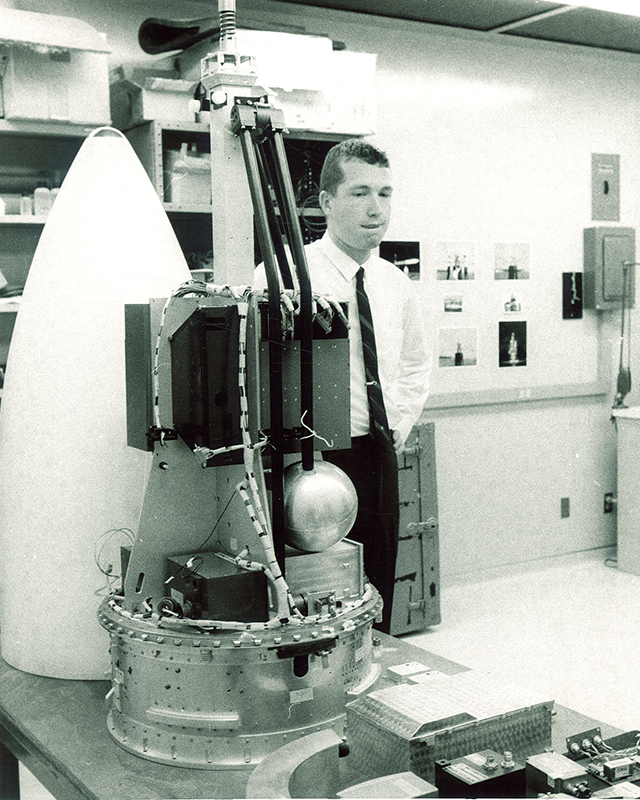

Joseph Senchuk is only in his second year at the University of Iowa, but he’s already building space instruments, extending the Iowa legacy of undergraduate involvement in space exploration.

The UI sophomore from Mount Prospect, Illinois, is helping build a prototype for a UI-designed and manufactured radar transmitter that is expected to fly on a spacecraft to Jupiter’s moons in 2022.

“It just amazes me,” Senchuk says. “I’m so blown away.”

For nearly sixty years, the UI has challenged and guided undergraduates like Senchuk to design, build, and test space instruments. The practice, which began with the first successful launch of an American satellite in the late 1950s, has propelled UI graduates into careers in aerospace, academics, and many other fields and earned the university a reputation for unique on-the-job training for those interested in space exploration.

“It’s kind of an apprenticeship,” says Donald Gurnett, longtime professor in the UI Department of Physics and Astronomy and himself one of the first undergraduates to be involved in space instrument research and development at Iowa. “You deal with hardware, not just theory. It’s truly a hands-on experience.”

More than 160 undergraduates have worked in the department over the past six decades, their handiwork and skills showcased in missions around Earth and on journeys to most of the planets in our solar system.

A history of pioneering exploration

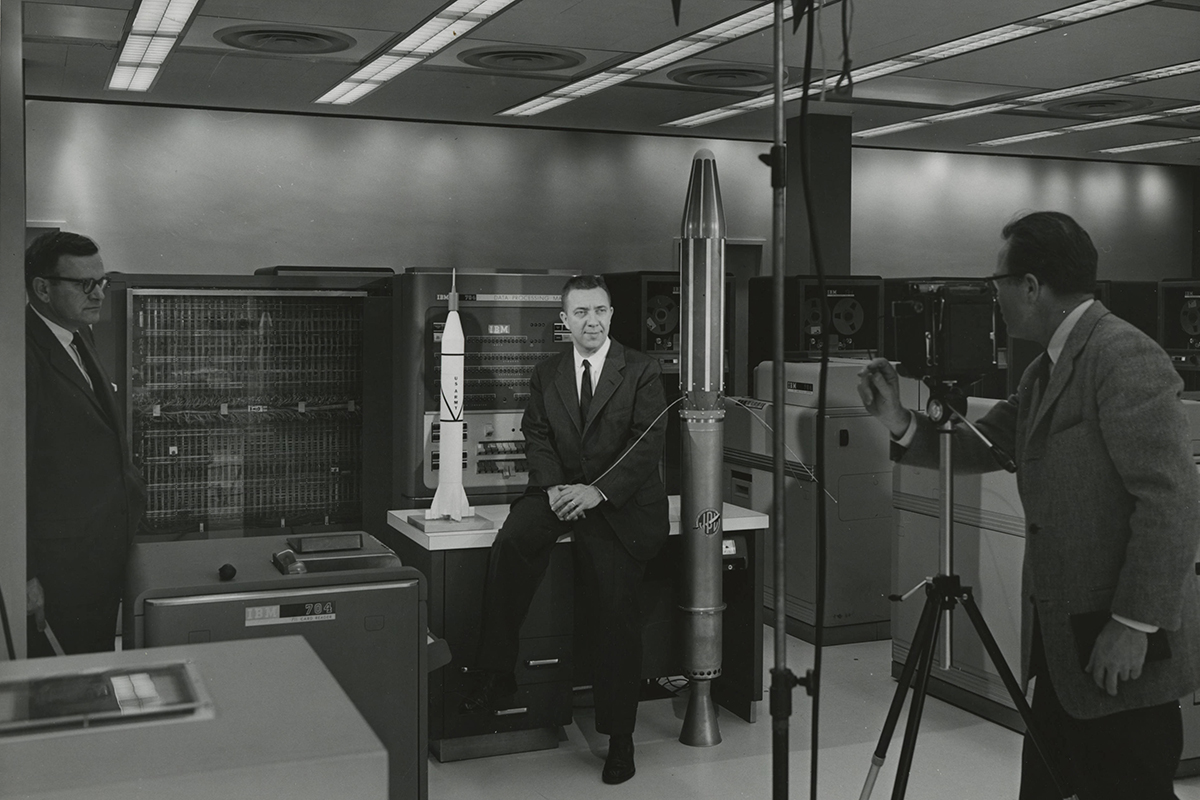

Gurnett was still a wide-eyed first-year student at the UI—he’d matriculated in the fall of 1957 at the age of 17—when he learned about the exploits of James Van Allen, the Iowa physicist and space pioneer whose successful January 1958 launch of the first American satellite into space, Explorer 1, is generally recognized as the beginning of U.S. space exploration.

Gurnett, a budding engineer who flew model airplanes and rockets in high school, had the gumption to approach Van Allen directly.

“I just couldn’t resist going over there and seeing if he had a job,” he says.

To Gurnett’s delight, Van Allen had plenty of work for him and other undergraduates. For the next three years, in the basement of the old physics building (now MacLean Hall), Gurnett helped design and create electronics, particle detectors, digital data systems, and other devices for a host of UI-built satellites and spacecraft for America’s burgeoning space program.

“It was a key thing in my life,” Gurnett says. “It got me involved in space research right at the beginning.”

Gurnett has since designed and built instruments for more than 35 missions within our solar system—and beyond. Through those instruments and his interpretation of the data they’ve provided, Gurnett can point to an array of important discoveries, including how auroras are created on Earth, Jupiter, and other planets; the first evidence of magnetic fields on Uranus and Neptune; Earth as a powerful radio wave source that led to the current search for Earth-like planets outside our solar system; and the Voyager 1 mission, which launched in 1977 and eventually left the solar system, entering interstellar space—the first man-made object to travel that far.

With these and other projects, Gurnett has carried on Van Allen’s legacy, passing on the excitement of space exploration to dozens of undergraduates through their direct involvement in instrument research and design.

“It’s a part of our operation, even today,” he says.

Building space instruments—and marketable experience

Alumni have pointed to their involvement in space instrument research and development as pivotal moments in their undergraduate careers.

Cassie Lee began working in a lab as a UI sophomore in 2000. She helped create a mechanical mock-up for how the antennas of the Mars Express Orbiter, a European Space Agency mission that launched in June 2003, would deploy. The UI participated in the design and construction of an instrument onboard the orbiter called the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS).

Lee, a mechanical engineering major from West Des Moines, Iowa, who graduated in 2003, says she was interested in aerospace even before she enrolled at the UI. Being involved in an actual space mission only strengthened that passion.

“It was hands-on, educational,” she says of her time at the UI. “I felt like I was part of something bigger.”

Her time in the department led to a connection with Mary Beth Koelbl, a UI alumna and department manager at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lee won a spot in NASA’s Cooperative Education Program at Marshall, and she traveled between Alabama and Iowa for the final two-and-a-half years of college.

The internship “shifted the course of my career,” says Lee, who now is a director at Vulcan Aerospace in Seattle, Washington, where she collects and interprets data obtained from satellites to help address global problems like climate change and ocean health.

“I would say the opportunity in the UI Department of Physics and Astronomy helped me realize that aerospace is the industry that I wanted to seek out and participate in professionally,” she says.

Looking toward the future

Today Senchuk, who plans to major in electrical engineering, is next in line to benefit from the UI’s legacy of undergraduate involvement in space missions.

The 20-year-old is involved in the lead-up to the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission, which will explore Jupiter and three of its moons that are believed to harbor internal oceans—and possibly microbial life.

On a recent morning, he was busy working with circuitry to test how well the planned radar detector will communicate with a satellite that feeds the mission’s data back to Earth. This summer, he will help build a radar transmitter prototype that will be tested by mission engineers. If it passes inspection, Senchuk may help design and build parts of the actual instrument that will be on the JUICE spacecraft for its planned launch in June 2022.

After only two years of undergraduate study, Senchuk’s résumé already stands out. At a UI College of Engineering job fair last fall, he visited only two booths, both of major defense contracting firms.

“I handed both of them my résumé, and the first thing they saw was the JUICE mission,” Senchuk says. “They were really taken aback by that.”

Though career decisions are at least a couple years away, Senchuk can relax knowing that he’s gaining invaluable experience in the testing lab, part of the Radio and Plasma Wave Group, headed by Gurnett.

“It’s genuinely interesting every day,” Senchuk says. “I’m baffled by how much I learn here.”