A mother’s gut feeling — and UI Health Care expertise across multiple pediatric specialties, plus ECMO life support — made all the difference for a young girl from Marengo, Iowa, with a rare autoimmune disease.

Story: Christina Hernandez Sherwood

Photography: Justin Torner and courtesy of Rhonda Goodman

Published: Aug. 12, 2025

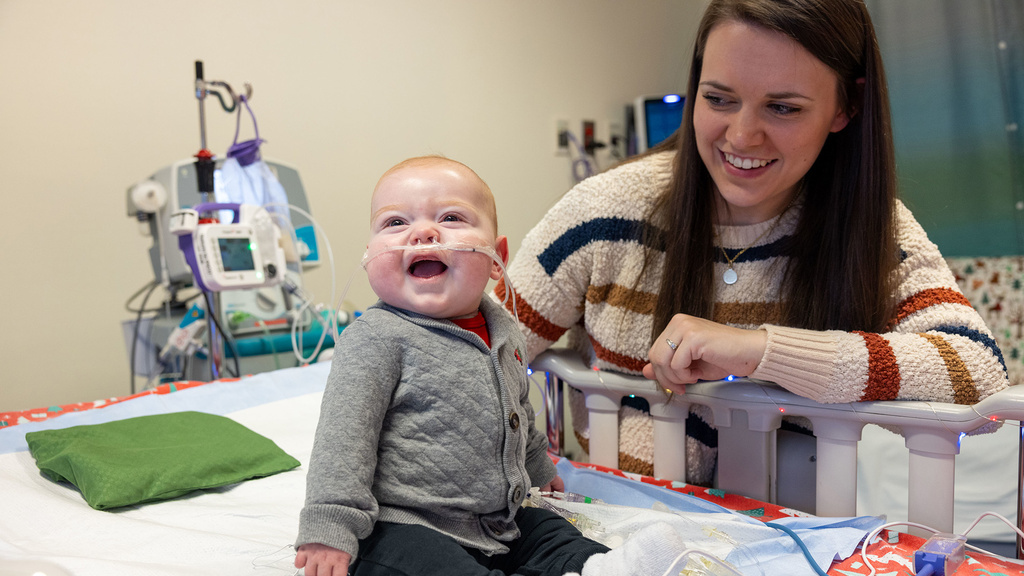

The top photo...

Rhonda Goodman (left) hugs her daughter, Payten Stout, who received care for a life-threatening condition at UI Health Care Stead Family Children's Hospital. “Watching these doctors and nurses, day and night, fighting to get her through this was one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen in my life,” Goodman says.

Twelve-year-old Payten Stout got sick slowly, then all at once.

Recurrent nosebleeds in fall 2024 gave way to a lingering viral illness in the winter. By early spring, Payten had bouts of shallow breathing that her mother, Rhonda Goodman, attributed to seasonal allergies exacerbated by the fields around their Marengo, Iowa, home.

But Payten’s condition took a dangerous turn in mid-April 2025 when she suddenly became critically ill.

“She started walking like she was drunk,” Goodman recalls. “She looked at me like a zombie. Her lips were white.”

Coordinated care from many pediatric specialties

At University of Iowa Health Care Stead Family Children’s Hospital, the only Level 1 pediatric trauma center in Iowa offering the full range of pediatric critical care therapies, Payten would need two forms of life support: continuous renal replacement therapy for kidney function and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), the highest standard of cardiovascular and pulmonary support.

She received coordinated care from teams in multiple pediatric specialties — critical care, nephrology, dialysis and kidney transplantation, rheumatology, allergy, and immunology; pulmonary medicine, and more — to keep her alive. And find out what was trying to kill her.

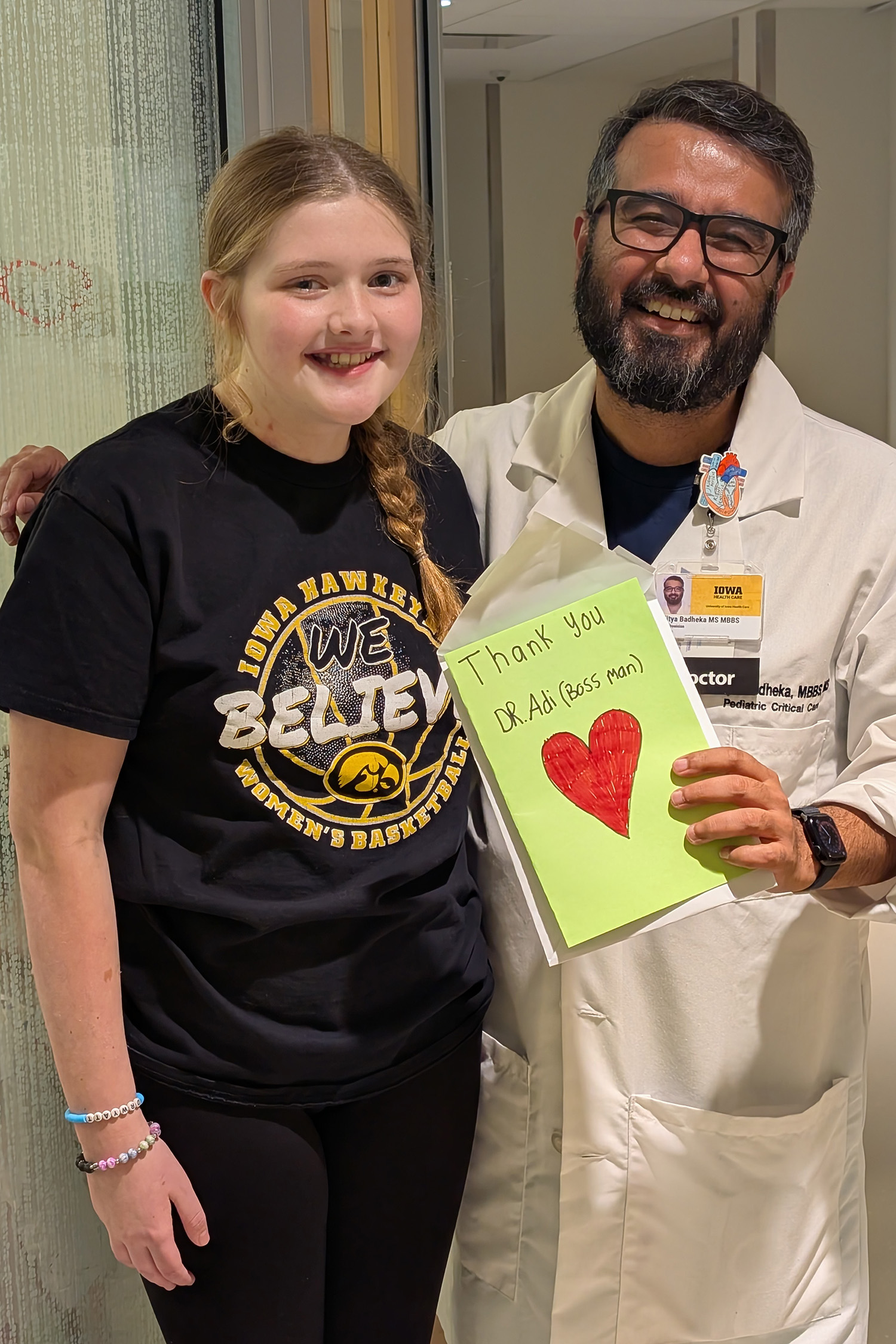

“It’s impressive to see how many services we have under one roof 24/7 and how skilled each of our providers are,” says Aditya Badheka, MBBS, MS (12R,15F), clinical professor of pediatrics–critical care and medical director of the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). “It truly takes a village to take care of a patient like her and to have a good outcome.”

A life-threatening condition

The weekend of April 12 was a busy one for Payten. She attended a sleepover party and was confirmed at church. Amidst the festivities, she took two naps, which was unusual, Goodman says.

Payten went to school the following Monday with a hard, hacking cough. That night at a birthday dinner for Payten's stepdad, Brian Mattison, she barely touched her chips and queso. Later that evening, Payten told her parents she had vomited. She didn’t think to mention she had thrown up blood.

On the morning of April 15, her mother’s 40th birthday, Payten asked to stay home sick. Her condition worsened throughout the day. She was pale, unusually tired, and breathing irregularly. When Goodman told Payten they were going to the hospital, the girl resisted with unusual force and disobedience. Payten kicked off her shoes and went “deadweight” as Goodman struggled to get her into the car.

“Payten has never in her life disrespected me like that,” Goodman says.

Payten Stout stands with her mom and stepdad at their family home.

She eventually called Mattison to come home from work to help take Payten to a community hospital in Cedar Rapids. Doctors would later tell Payten’s parents she had been in fight-or-flight mode due to a severe lack of oxygen. This caused her uncharacteristic behavior.

When Payten arrived at the Cedar Rapids hospital’s emergency department, providers put a pulse oximeter on her finger to check her blood oxygen saturation. The room went silent. An oxygen saturation reading below 92% requires immediate medical attention. Payten’s oxygen saturation was 55%

Payten was rushed to a trauma suite as a social worker pulled her parents into a private family room.

“[The social worker] says, ‘Your daughter is really sick. Would you like a chaplain?’” Goodman recalls. “I’ve worked in health care. I know what it means when I’m being asked that.”

Payten had a pulmonary hemorrhage, which is acute bleeding in her lungs. Providers placed a breathing tube and put her on a ventilator to help her breathe. They made plans to transfer her to Stead Family Children’s Hospital for more specialized care than the local hospital could offer. A 20-minute ambulance ride would take too long, so she was airlifted. When Payten heard she was going on a helicopter, she was excited despite being seriously ill.

“I’ve never been in one,” she recalls. “Then they put a mask over my face, and I fell back asleep.”

She wouldn’t wake up for days.

Critical care for life-saving support

Payten’s condition continued to deteriorate on the eight-minute flight. She was rushed to the PICU at Stead Family Children’s Hospital, where a team was waiting.

Along with severe bleeding in her lungs, Payten’s kidneys were functioning at about 15% of their normal capacity, according to pediatric nephrologist Kyle Merrill, (16MD, 19R), MS. She also began to go into shock, a life-threatening emergency.

“Payten’s condition was dangerous and getting worse,” Merrill says. “She nearly died on us.”

Her care team sprang into action. Clinicians worked to stabilize her dangerously inflamed organ systems with steroids and other medications. The team interviewed Payten’s parents and aimed to identify her diagnosis.

“This is a previously healthy girl who was having serious, non-specific symptoms,” Badheka says. “Mom made a great decision to take her to the [emergency department]. The [Cedar Rapids hospital] made a great decision to send her to us. This interconnectedness of actions and the chain of survival was needed to maximize Payten's chances of survival and recovery.”

It soon became clear, Badheka says, that Payten would need ECMO, the highest level of life support for patients with severe heart and lung failure. ECMO is a temporary therapy that takes over pulmonary and cardiovascular function. It’s a lifesaving measure but an invasive procedure with a high risk of complications, including bleeding and clotting.

Badheka alerted the ECMO team, the blood bank, and cardiothoracic surgeon Yuki Nakamura, MD, that ECMO activation was necessary. He also discussed the subject with Payten’s parents. He drew them a simple diagram of the complex ECMO circuit, explained the risks, and answered questions. He also reassured them that specialists at Stead Family Children’s Hospital see about 20 ECMO cases a year.

It was a difficult conversation. Goodman, who had never heard of ECMO, found the prospect terrifying.

“Everything is getting worse,” she says. “It felt like I was going to lose her. I put everything on my faith.”

It was time to act. Payten’s lung function — both oxygenation and carbon dioxide elimination — was worsening to a critical degree. The ventilator needed too much pressure to support Payten’s compromised lungs.

“Lung failure was happening in front of our eyes,” Badheka says. “She needed the highest level of support.”

What is ECMO?

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, is a therapy that adds oxygen to your loved one’s blood and pumps it through their body like the heart. The process takes place outside the body.

ECMO is like a heart-lung machine used in heart surgery and can be used for longer periods of time. ECMO temporarily takes over the work of the heart and lungs so they can rest and heal.

ECMO is used when usual treatments are not working. ECMO does not cure heart or lung disease, it only provides time for the patient’s heart or lungs to heal.

“She was fighting to stay alive. Watching these doctors and nurses, day and night, fighting just as hard to get her through this was one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Expertise in ECMO

To put a patient on ECMO to provide lung support, a surgical team first places large tubes (cannulas) in a vein, typically the internal jugular vein in the neck. Blood from the vein is diverted from the body to the ECMO system, which sits at the patient’s bedside. The machine circulates the patient’s blood, adding oxygen and removing carbon dioxide just like healthy lungs. The oxygenated blood is then transferred back through the cannula to the patient to be circulated to the rest of the body.

An international leader in ECMO, UI Health Care is among approximately 30 health systems worldwide to receive the highest level of award for excellence, Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Award for Excellence in Life Support–Platinum Level. UI Health Care’s ECMO experts train medical professionals around the globe on how to use this life support system.

A patient on ECMO is treated by the entire ICU team and a specialized ECMO team. A trained ECMO specialist remains by the patient’s bedside around the clock to monitor the machine and ensure it is functioning properly.

“It’s doing the job of the lungs to let the lungs rest,” Badheka says. “In the meantime, we can figure out what’s going on and treat the root of the problem.”

A rare diagnosis: ANCA-associated vasculitis

By the next morning following her hospitalization, Payten’s diagnosis had come into focus. A multispecialty team that included specialists in pulmonology, rheumatology, and nephrology determined that she had anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, a rare autoimmune disease that inflames and damages small- and medium-sized blood vessels, causing leakage and low blood supply. ANCA-associated vasculitis is a generalized disease that affects all organ systems, but most acutely targets the sinuses, lungs, and kidneys.

“Her own immune system was working against her and causing unnecessary damage,” Badheka says. “This is such a difficult diagnosis to catch. You don’t see any obvious symptoms.”

Payten’s disease flare-up was most likely caused by a trigger, such as the viral illness she experienced earlier in the year, Merrill says.

“Maybe there are some vague symptoms beforehand,” he says, “but it is truly a disease that presents in the blink of an eye.”

Payten Stout stands with Aditya Badheka, MBBS, MS, clinical professor of pediatrics–critical care and medical director of the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). “It truly takes a village to take care of a patient like [Payten] and to have a good outcome,” Badheka says.

Stead Family Children’s Hospital specialists see about one ANCA-associated vasculitis patient a year. Payten’s case was one of the most serious the team had ever encountered.

“If you have vasculitis and you present with multi-organ failure, where your kidneys and lungs don’t work,” Badheka says, “your chance of death is very high.”

Kidney support and plasma exchange treatments

Payten’s time on ECMO was complicated by the other supportive services she needed. Continuous renal replacement therapy, which refers to around-the-clock dialysis treatment to support kidney function, was administered through the ECMO circuit. At the same time, Payten also received plasma exchange treatments, facilitated by the hospital’s blood bank, through the ECMO system. The treatment removed Payten’s plasma, along with the antibodies that were causing her illness, and replaced it with donor plasma. Finally, Payten was treated with a drug cocktail of steroids, kidney inflammation medication, and a drug that suppressed antibody production.

In her hospital bed, Payten was barely recognizable amid the tubes and machines, but Goodman says she never questioned whether Payten was in the right place.

“She was fighting to stay alive,” she says. “Watching these doctors and nurses, day and night, fighting just as hard to get her through this was one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Payten Stout and her parents look at Kinnick Stadium from the 12th floor of UI Health Care Stead Family Children's Hospital during Payten's stay.

Recovery and ‘inspiration’

Within days, recovery for Payten seemed within reach.

“I remember one morning, [doctors] pulled up her lung X-ray and compared it to the day before,” Goodman says. “All of a sudden, you could see little pieces clearing.”

Payten came off ECMO after eight days, surprisingly early for the severity of her case and under the average of two weeks. Her kidneys recovered enough to function without dialysis.

“Payten’s recovery is a testament to the coordination of care between our PICU team, our ECMO team, our blood bank, our dialysis team, the nephrology team, and rheumatology,” Merrill says.

Being hospitalized with a critical illness for weeks can cause a child’s functional skills, such as walking and fine motor abilities, to regress. Before she left the hospital, Payten needed to re-learn how to hold her head up, chew and swallow food, and walk. But she didn’t need in-patient rehabilitation, as doctors originally thought.

“We still have a long way to go, but Payten is resilient. She’s been that way since the day she was born,” Goodman says. “She’s an inspiration.”

Payten flexes her muscles at UI Health Care Stead Family Children's Hospital several weeks after she was discharged.

Seamless collaboration in crucial moments

Successful management of a critically ill child often hinges on seamless collaboration across multiple specialties, with each bringing unique expertise to the table.

In terms of Payten’s care:

- The PICU team played a pivotal role in stabilizing and optimizing Payten’s vital body functions.

- Cardiothoracic surgeon Nakamura led the effort to place her on ECMO.

- The nephrology team coordinated with the PICU team to manage fluid balance and renal support, which are critical when ECMO and surgical interventions put significant strain on multiple organ systems.

- Pulmonology specialists were essential in managing lung issues related to ANCA-associated vasculitis.

- The rheumatology team was essential in diagnosing the problem and tailoring immunomodulatory treatments to prevent further organ damage while balancing the risks of infection and immunosuppression.

This approach in cases like Payten’s fosters continuous communication and coordinated plans, Badheka notes, which supports better outcomes by addressing complex care needs holistically.

“The integration of these diverse service lines not only enhances survival but also improves long-term recovery and quality of life for the child and family,” Badheka says.

Payten Stout throws a softball to her stepdad at her family home in August 2025.

Keeping vasculitis in check and living with chronic kidney disease

More than a month after Payten was admitted to Stead Family Children’s Hospital, she went home. She returned to school on May 30, her last day of seventh grade.

It’s possible that her ANCA-associated vasculitis will flare up again, Merrill notes, so she needs ongoing management. Payten, now 13 years old, began immunosuppression infusions in the hospital that will continue for at least two years.

“We want to keep her disease in check,” Merrill says. “It’s a long-term battle now to try to keep her disease quiet, to minimize side effects, and to get her back into regular life.”

Payten’s kidneys were permanently scarred. Her kidney function is about half what it should be, Merrill says, meaning she has chronic kidney disease. It’s likely that she’ll need a kidney transplant one day.

Still, Merrill says, “I’ve had several ANCA patients never recover their kidney function. While [Payten] has had a rougher course, she’s had better kidney recovery.”

Parents can learn from Payten’s story — and her mother’s gut instinct to seek care for her daughter, according to Badheka.

“If your intuition is saying something is wrong, make sure to get checked out,” he says. “The intuition that parents have is sometimes the best tool. That’s exactly what Payten’s family had.”