Iowa dives into the future of water research

For nearly a century, University of Iowa researchers have studied the science and technology of water management. From the impact of floodwaters after heavy rainfall to the way a ship slices through the sea, researchers use field research, laboratory experimentation, and computational analysis to comprehend, master, and protect one of Earth’s most precious resources—water.

Over the years, UI research has improved the flow of storm water through pipes beneath busy city streets, shaped the course of the Mississippi River, provided safe passage over dams for migrating salmon, and helped identify dangerous industrial byproducts that pollute lakes and harbors across the country.

Today, with even bigger goals in mind, UI researchers are using advanced technology to monitor stream levels and improve flood preparedness, and they are documenting the existence of airborne carcinogens such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in building materials, paints, and wood sealants. On the UI’s health care campus, researchers are using hydroscience concepts to better understand the unique fluid mechanics of the human heart and lungs.

With the recent hiring of a cluster of water experts and the kickoff in 2017 of a new graduate program in water, food, and energy sustainability, the UI stands ready to tackle some of the toughest problems of the 21st century, including dramatic weather change, flooding in areas plagued by poverty and social ills, and environmental pollution and degradation that threaten future life.

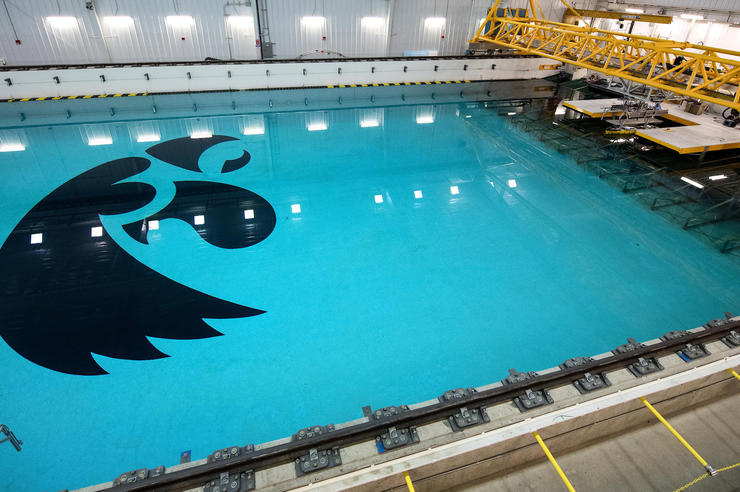

“The University of Iowa’s immense expertise in hydroscience comes as a surprise to some, but over the past century, we have emerged as a national and international leader in the field,” says Larry Weber, executive associate dean UI College of Engineering and former director of IIHR—Hydroscience and Engineering, a research institute that encompasses an impressive network of labs and work groups, including one of most technologically advanced wave basins in the nation, and the first university-owned research and education center on the upper Mississippi River, the Lucille A. Carver Mississippi Riverside Environmental Research Station.

This concentration of hydroscience research, teaching, modeling, and experimentation at the UI is difficult—if not impossible—to match anywhere in the world.

“What differentiates us is a special combination of human capital and physical infrastructure,” Weber says. “It’s knowing that we have the ability to do the research we want and need to do because the university has created an environment of support, freedom, and trust.”

Hydroscience research at the UI began in 1920 in a 500-square-foot laboratory on the Iowa River. Nearly a century later, the university has eight annexes, labs, and shops dedicated to the science and technology of water management, including one of the largest indoor wave basins in the nation.

A source of big ideas from the start

Hydroscience research at the UI began in 1920 in a 500-square-foot laboratory on the Iowa River. Despite the institute’s humble beginnings, Floyd Nagler, the first director of the Iowa Institute for Hydraulic Research, was quick to tackle important projects, including a comprehensive survey of the Mississippi River’s tributaries, and groundbreaking work in the design of culvert pipes needed to support the nation’s rapidly expanding highway network. Nagler also built the C. Maxwell Stanley Hydraulics Laboratory, a landmark, five-story brick building that houses IIHR to this day.

Nagler was followed by an impressive succession of directors, including Hunter Rouse, who in the 1950s and ’60s used his stature as the “father of modern hydraulics” and personal connections with academic institutes around the world to expand IIHR’s reputation, setting it on track for international prominence. Jack Kennedy, IIHR director from 1966 to 1991, ushered in an important period of growth in terms of budget and staff, as well as the addition of new poles of expertise to reflect a new era of environmental concerns, including water use and pollution control.

The University of Iowa’s long history of hydroscience research, teaching, modeling, and experimentation is difficult—if not impossible—to match anywhere in the world.

One of the staff members Kennedy recruited was A. Jacob Odgaard, a civil and environmental engineer from Denmark. Odgaard, who recently retired after four decades at the university, says he was almost overwhelmed by Kennedy’s insistence that he come to Iowa. “Jack wouldn’t take no for an answer,” Odgaard says. “He told my boss that he was recruiting me before he told me that he had a job for me.”

Odgaard says he doesn’t regret the move to Iowa. As part of a project for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, he and Kennedy created submergible vanes to keep riverbed sediment from washing away with the current, thereby reducing bend scour and bank erosion. The researchers’ 1983 paper on the vanes was groundbreaking at the time and resulted in similar projects for the research institute. Even today, when faced with a dilemma, Odgaard says he thinks about the man who brought him to Iowa. “What would Jack have done?” he says. “I learned so much from him.”

The next leader of hydroscience activities at the UI was Virendra C. Patel. Educated at Imperial College in London and Cambridge University in Cambridgeshire, England, Patel came to Iowa in 1970 as a research professor. He studied turbulent shear flows, wind engineering, and ship hydrodynamics, and was a whiz on the computer. When Patel was named IIHR’s director in 1994, he made plans for a series of building and technology updates and secured funding to build the Hydraulics Oakdale Annex Two, an 11,300-square-foot structure used to test large-scale fish-passage models and storm water conveyance structures—two areas of research that flourished under his leadership.

“Patel was the director who took a healthy IIHR into the 21st century by combining the best of those who had gone before him,” says Cornelia F. Mutel, retired IIHR senior science writer and the author of Flowing Through Time: A History of the Iowa Institute of Hydraulic Research.

Leading the way through research and outreach

After Patel, Weber, a hydraulic engineer and early leader in ecohydrology, took the reins of IIHR. Weber obtained his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees at the UI and has a deep knowledge of the institution and its history. As a researcher at IIHR, Weber used his expertise in environmental hydraulics and fluid mechanics to help preserve fragile fish populations in the Pacific Northwest. In 2003, he was part of a team of researchers who received one of the largest research contracts in UI history: a nearly $7 million, three-year contract extension from a public utility district in Washington state to study how salmon could coexist with hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River.

Like his predecessors, Weber’s expertise and talent helped shape the direction of hydroscience research at the UI, and during his 13-year tenure at the helm of IIHR, its approach to research became more holistic, connecting hydroscience studies to larger environmental and sustainability movements. As part of this new vision, IIHR intensified research into the role of nitrates, a byproduct of agricultural activities, and the degradation of the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico beyond it. Given IIHR’s location in the Midwest and Iowa’s status as a top producer of corn and soybean crops in the Mississippi River basin, Weber was eager to take on a leadership role.

In 2013, Weber worked with other researchers and state legislators to create the Iowa Nutrient Research Center (INRC), which oversees a number of science-based projects aimed at reducing the amount of nutrients, including nitrates, entering Iowa waters and the Gulf of Mexico. The INRC’s work involves the collection of raw data from a network of water-quality sensors in rivers and streams across the state, as well as evaluating the performance of current and emerging nutrient management practices and providing recommendations on implementing the practices on working farms.

“With Larry, it wasn’t just about water flow in a river,” says Mutel, “but the whole picture, the entire watershed, even up into the hills.”

After the flood

In 2008, an unusually wet winter and spring and a deluge of rain in early June caused streams to overflow and rivers to swell to historic levels. It was a year for the history books—for the state of Iowa and for hydroscience research at the UI. Flooding caused an estimated $10 billion in damage statewide and left thousands of Iowans homeless. Eighty-five of Iowa’s 99 counties were declared federal disaster areas. As they watched the disaster unfold, Weber and IIHR colleague Witold Krajewski, a hydrologist trained in Poland, came up with an idea to create a research center within IIHR that would put hydrologic and river-hydraulic expertise to work for Iowans.

With support from state legislators and local officials, Weber and Krajewski created the Iowa Flood Center (IFC), the nation’s only academic center devoted solely to flood-related research. Today, with Krajewski at the helm, the IFC’s staff of research experts work to protect Iowans from flooding and its devastating results through advanced technology and science, targeted conservation practices for flood mitigation, and strong community partnerships.

An example of the IFC’s work is the Iowa Watershed Approach, a program that aims to reduce flood risk and increase flood resilience through close collaboration with residents, landowners, agencies, and local officials. Funding for the program, which operates in nine watersheds across the state, comes from a $96.9 million grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The program is now in its second year, and Weber and Krajewski say they are encouraged to see local residents stepping up to take control of watershed actions.

“They have really taken ownership and are adapting the program to meet their individual watershed needs,” says Weber. “This is exactly the kind of local stewardship we envisioned.”

“When I think about all of the research activities currently underway, I can say that the University of Iowa is in a leading position to tackle some of the most important societal problems of our time.”

New challenges, new leadership

In 2017, Weber stepped down as director of IIHR to take a leadership role in the UI College of Engineering, but before going, he tapped Gabriele Villarini, a hydrologist from Italy, to replace him as head of the research institute. Villarini is part of a new generation of scientists and researchers at the UI that is working to sustain the university’s distinguished reputation in hydroscience study. Some of the new researchers came to the UI as part of a university-wide push to address some of the biggest challenges of the 21st century, including providing access to clean water and managing the nitrogen cycle. Members of the UI’s Water Sustainability Initiative include researchers with expertise in the politics of providing clean drinking water; the chemistry of advanced water treatment; environmental contaminants; environmental signal processing; and the intersection of science, communication, and public policy.

“With these new hires, the university was really focused on bringing in new ideas and creativity,” says Jerald Schnoor, professor of civil and environmental engineering and co-director of the UI’s Center for Global and Regional Environmental Research. “There was a focus on producing more interdisciplinary research, which is why there are scientists and engineers, but also economists and journalists.”

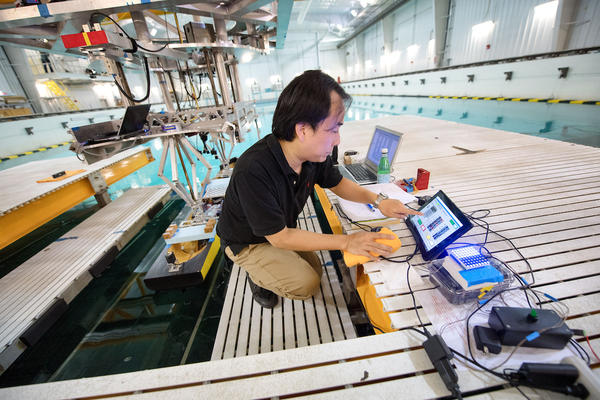

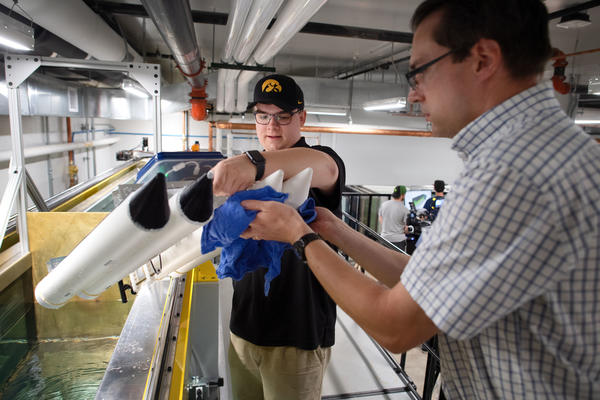

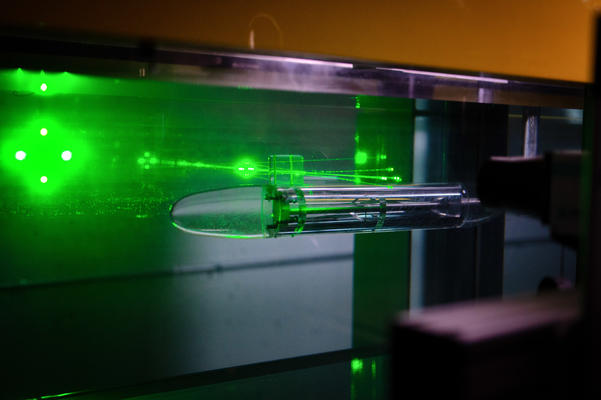

The UI’s reputation as a leader in hydroscience research helps attract top talent. Casey Harwood, an assistant professor of mechanical and industrial engineering and an expert in naval architecture and marine engineering, says a chance to work in the UI’s state-of-the-art research labs, including the towing tank and wave basin, definitely was enticing.

“I knew that Iowa was the standard by which a lot of other institutions measured their research activities and results,” says Harwood. “For me and a lot of people in the world of naval hydrodynamics, Iowa is synonymous with methodical and scientifically rigorous experiments.”

The UI’s reputation also attracted Villarini, who chose to leave his native Italy in 2003 to pursue a doctorate at the university, where he worked under the mentorship of Krajewski. After he witnessed the devastation that followed the 2008 flood, Villarini decided to make extreme weather a main focus of his research. In recent years, he has studied tropical cyclones and atmospheric rivers, as well as food and water sustainability, with an emphasis on understanding the causes and processes responsible for these extreme events.

“I have two daughters, and when I think about what the future might look like for them if we don’t take action, if we don’t act now, I feel uncomfortable,” says Villarini. “I strive to produce science that has a purpose, that will have an impact, not just for my generation but for my kids’ and grandkids’ generations too. Thinking about it in this way, it really makes me that much more motivated to do my best and succeed.”

As the new leader of IIHR, Villarini says he believes the research institute is ready to take on even larger research projects—projects that will rank among the largest and most significant in the UI’s long history of hydroscience study. These projects, he says, will draw on the expertise of scientists and researchers from many different fields, and will contribute to the larger, international debate among scientists, engineers, medical professionals, business leaders, educators, and social innovators about the future of the planet and humanity’s role in protecting it.

“When I think about all of the research activities currently underway, I can say that the University of Iowa is in a leading position to tackle some of the most important societal problems of our time.”

Learn more about hydroscience at the University of Iowa.