An innovative solution to a child’s breathing issue

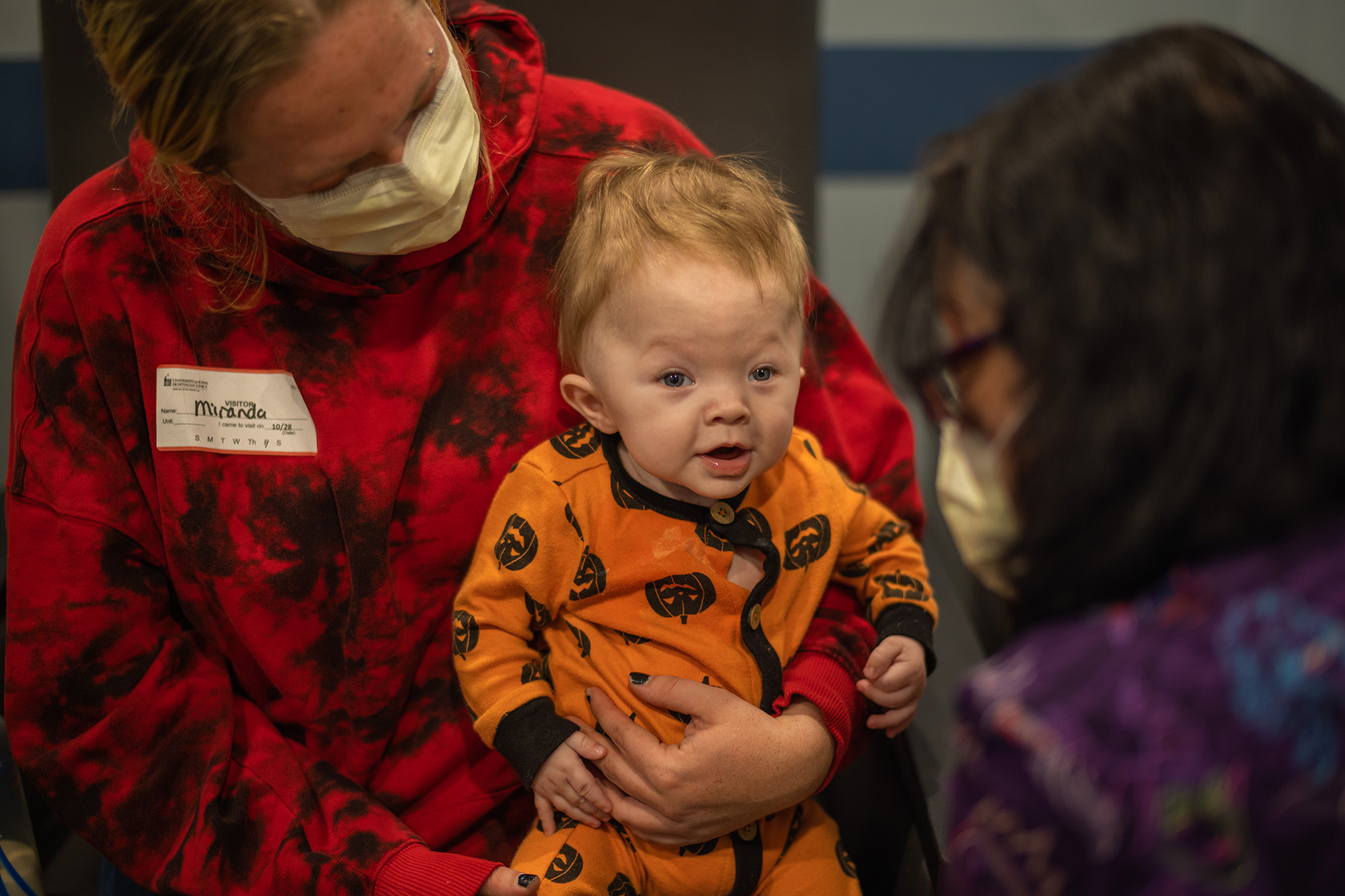

When Beau Needs was born prematurely with a floppy airway (tracheomalacia), he could not breathe. He needed a life-saving surgery to open up his airway, but the most common treatment for his condition is a tracheostomy—a tube inserted through the neck into the trachea (windpipe) to help keep the airway open to make breathing possible.

Beau’s mother, Miranda, already had two children with special needs at home, and the idea of caring for an infant with a trach was daunting.

“I was super emotional about it because it’s just another thing, it’s a big thing,” she says. “And it’s a long-term thing for most kids.”

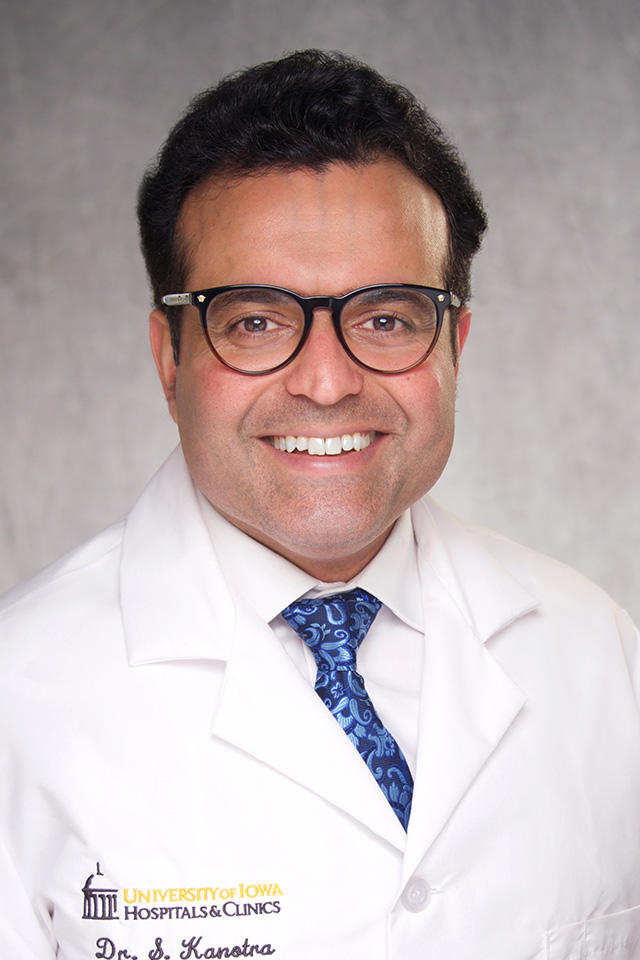

Sohit Kanotra, MD

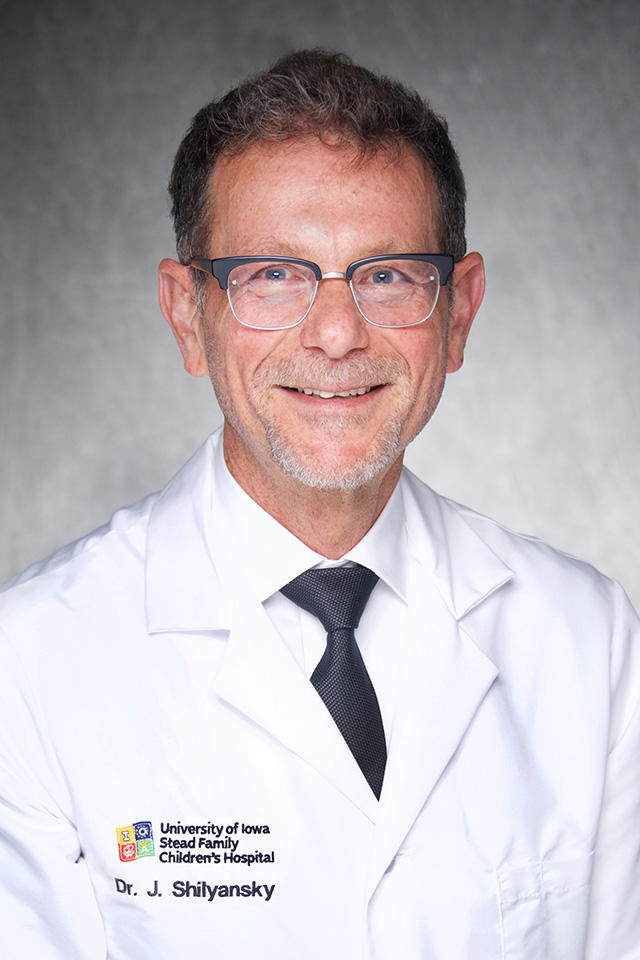

Joel Shilyansky, MD

Miranda was eager to find an alternative treatment option that would lead to a much better quality of life for her son and require less hands-on care once Beau was discharged from the hospital.

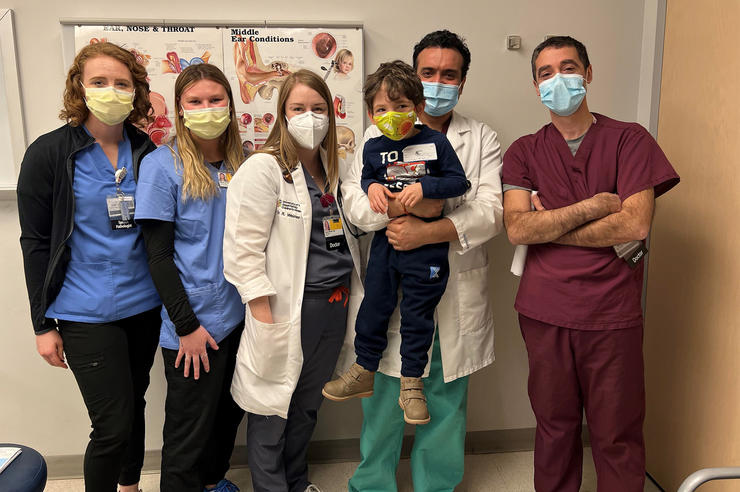

Thanks to an innovative new technique, Miranda didn’t need to worry. Beau’s surgery team at University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital performed the first posterior tracheopexy in Iowa to permanently correct the weak trachea.

A new treatment for tracheomalacia

Beau was born with tracheomalacia, a condition in which the cartilage in the trachea doesn’t develop properly, causing it to be “floppy,” or weak. The weakened cartilage can’t keep the trachea open, making it difficult to breathe.

“If you look at the windpipe—or trachea—the front wall is cartilage and the back wall is muscle, and with tracheomalacia that area can be weak and not stay open like it is supposed to in order to let you breathe freely,” says Sohit Kanotra, MD, otolaryngologist and director of the Aerodigestive and Tracheostomy Clinic at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital. “It is essentially collapsing from the backside and completely closing down the trachea because that muscle is weak.”

In the new procedure, surgeons tack the back wall of the trachea to the patient’s spine, preventing the trachea from collapsing and allowing free flow of air. In the past, surgeons would perform either a tracheostomy or an anterior aortopexy, a procedure that pulls the front of the trachea forward but did not work for Beau. This was the first time surgeons in Iowa had performed the posterior tracheopexy.

“This procedure doesn’t allow the trachea to collapse anymore and keeps the windpipe open. And Beau was able to breathe on his own, just a few days after the surgery,” says Joel Shilyansky, MD, director of pediatric surgery and surgeon-in-chief at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital. “Beau was able to get rid of the breathing tube and breathe without help, and that is a really huge thing for this baby.”

“He has several small armies taking care of him here, and he’s doing fantastic now.”

The UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital Aerodigestive and Tracheostomy Clinic focuses on a holistic, individualized approach when caring for your child. Ranked among the top otolaryngology programs nationally, the clinic provides comprehensive, coordinated evaluation and management of complex airway and swallowing disorders.

Collaboration between departments leads to excellent outcomes

In addition to tracheomalacia, Beau was also born with hydrocephalus—excess fluid on the brain—and agenesis of the corpus callosum, meaning he is missing a part of his brain that connects the right and left hemispheres.

Because of the combination of his conditions, Kanotra says Beau’s tracheomalacia posed a higher risk.

“The potential for a life-threatening episode is very real with Beau; if he were to have a full collapse of his windpipe, he would not be able to breathe,” he says. “Even with the tracheostomy, if it falls out or gets blocked, the child has no way to breathe. So we were glad to be able to provide an innovative solution for a difficult and life-threatening health problem though the collaboration between the aerodigestive team and the skilled surgery team.”

Miranda is pleased with the results and grateful for the teams that came together to help Beau breathe on his own.

“He has several small armies taking care of him here,” Miranda says of the hospital. “And he’s doing fantastic now. Other than occasionally being a little fussy, I think he’s just like any other baby. We have medications and breathing treatments, but he’s not on oxygen or pressurized air—he just breathes like the rest of us. And that’s great for him.”