Returning to the classroom after surviving COVID-19

For 30 days last fall, Jaime Humes was on an advanced form of life support that did the work of her heart and lungs so her vital organs could recover from the effects of COVID-19.

The teacher from DeWitt, Iowa, survived with the help of her care team. While she is still dealing with some aftereffects of the virus, she returned to her kindergarten classroom this fall. She was recently honored for 20 years of service in her school district.

“I don’t have memory of the surgeries, or memory of me getting so bad,” Jaime says. “But I have all the memories of the staff. I remember all of my doctors. They were all so wonderful.”

Searching for help

For two weeks in late August and early September 2020, Jaime stayed isolated in a hospital room near DeWitt, diagnosed with COVID-19 and pneumonia and unable to see family or friends. The only human contact she had was with the members of her care team, who monitored her oxygen levels, administered medications, or changed her body position. They were covered in full personal protection equipment (PPE), hiding most of their facial features, adding to the sense of isolation.

Jaime couldn’t breathe on her own and was on a ventilator, and her condition continued to deteriorate.

Unwilling to accept his wife’s dire prognosis, Don Humes called a doctor friend for advice and was told he needed to ask for a transfer to a hospital that could provide extracorporeal membrane oxygenation—or ECMO—to take on the work of her lungs and give them a better chance to heal. Don called multiple hospitals to find one that offered ECMO but, because of the pandemic, hospitals were already full. Then, University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics in Iowa City called to let him know they had a bed for Jaime. Within hours she was transferred by helicopter to Iowa City.

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) is a complex machine that requires a dedicated team of specialists, with 24/7 bedside monitoring to deliver this life-saving care for patients with critical heart and lung illnesses such as lung or heart failure.

University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics is one of 31 ECMO Centers of Excellence in the world with Gold Level standing. Iowa has more than 20 years of experience in providing ECMO support for neonatal, pediatric, and adult patients.

Being careful

When coronavirus-19—COVID-19—first arrived in Iowa in March 2020, Jaime and her family, like many Iowans, had been hearing what was happening in states such as New York and Washington. As a teacher, Jaime, 44, kept an even more watchful eye on the virus, not knowing how it would affect her classroom, her students, or her family.

For months, the Humes family followed the guidelines including wearing masks, social distancing, and avoiding large gatherings.

“We social distanced from our family, which was really hard—that’s not something anyone wants to do,” she says. “No one knew how long this was going to last, but we did the best we could to stay safe.”

In the middle of August 2020, however, Jaime started getting sick, first with a slight fever and a dry cough, “pretty mild symptoms that I just thought were my allergies,” she says.

Then her fever started to climb; after a few days she went to get tested for COVID. Her test came back positive.

‘I knew something was wrong’

Jaime’s fevers continued for more than a week and wouldn’t break, and she started to get additional symptoms, “similar to strep throat or the flu, but mine just kept getting worse.”

Then she started having difficulty breathing. That’s when she decided to go to her local hospital.

“My coughing wouldn’t stop, it was hard to control, and I could tell my lungs were having a hard time filling,” she says.

And the fever just wouldn’t go away.

“I’ve never had a fever that long,” she says. “I knew something was wrong. It wasn’t normal.”

Jaime Humes remained on ECMO for 30 days and was at UI Hospitals & Clinics for more than six weeks. She had multiple surgeries—several where it wasn’t certain if she’d pull through. “I don’t have memory of the surgeries, or memory of me getting so bad,” Jaime says. “But I have all the memories of the staff. I remember all of my doctors. They were all so wonderful.”

An X-ray at the local hospital didn’t show anything, but when doctors did a CT scan of Jaime’s lungs, they could see the beginning of pneumonia.

“The pneumonia looked like fairy dust in my lungs,” Jaime says.

She was transported by ambulance to a hospital in the Quad Cities where she was admitted to the COVID unit. After a few days, doctors took another X-ray: pneumonia had filled her lungs.

Doctors talked about intubating her, but Jaime resisted at first.

“After I was transferred, I got really nervous because all we’d been hearing is that if you get COVID and have to go to the hospital, and if you have to be intubated, you’re probably not going to make it,” Jaime says. “I kept telling the doctor, ‘Don’t intubate me, don’t do that to me.’”

Jaime stayed in the Quad Cities for two weeks but her condition continued to deteriorate. Her care team couldn’t get her oxygen levels where they needed to be, despite a variety of treatments. As a result, she was intubated and transferred to UI Hospitals & Clinics.

Not out of the woods

As soon as Jaime arrived in Iowa City, she had to be re-intubated. In the middle of the night, Jaime’s condition took a turn for the worse, and she had an emergency placement on ECMO, a life support system that takes the stress off the heart and lungs, so they have a chance to recover. It’s only used in cases in which every other option has been exhausted.

Jaime remained on ECMO for 30 days and was at UI Hospitals & Clinics for more than six weeks. She had multiple surgeries—several where it wasn’t certain if she’d pull through.

Though she had tested negative for COVID shortly after arriving in Iowa City, Jaime was still fighting COVID-related pneumonia, as well as other symptoms. Her muscles were weakening the longer she was in bed.

But she was determined.

“One thing that really helped me was I always did what the doctors wanted me to do,” she said. “I didn’t want to do physical therapy, but I did it because the doctors said it would help. And it did. When October came, I was finally starting to see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

If you’ve recovered from COVID-19, it’s important to continue to watch your health closely. COVID-19 is a new and relatively unknown disease. The short- and long-term effects it can have on your body are still not clear.

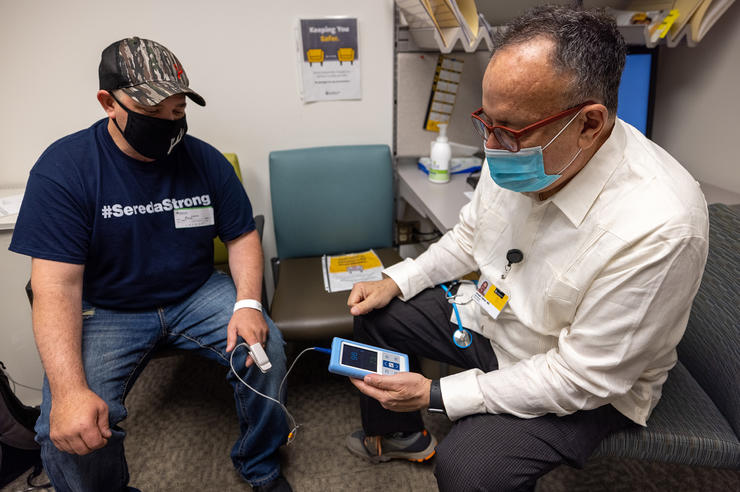

University of Iowa Health Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic is the state’s only clinic dedicated to caring for people who have recovered from COVID-19.

Jaime was taken off ECMO in early October and discharged on Oct. 23, 2020. She continued to need oxygen supplement at home, and began twice-weekly sessions of occupational and physical therapy at her local hospital that would last for several weeks. She also made regular visits to UI Hospitals & Clinics’ Post-COVID-19 Clinic, which cares for patients with long-term effects from COVID. By early March 2021—seven months after being diagnosed with COVID—Jaime still hadn’t returned to work.

“I’ve come a long way but it’s taken a lot of baby steps to get here,” Jaime said at the time. “I have to be careful about what I do, I get tired very easily—and that’s not easy for someone who wants to be active.”

Jaime says she’s come to appreciate the small things more—and the value in faith, family, and friends, many of whom helped Don with the kids while she was in the hospital.

She gets frustrated by people who continue to say COVID isn’t serious.

“I guess what I would want people to think about is even if you think you’re invincible, even if you think you’re not going to get it, or you won’t get it really bad, you’re probably right,” she says. “But there are 1% to 5% of us who, for whatever reason, get it pretty badly, and some will die. I think people just need to be more serious about it.”