Improving quality of life for the youngest cancer survivors

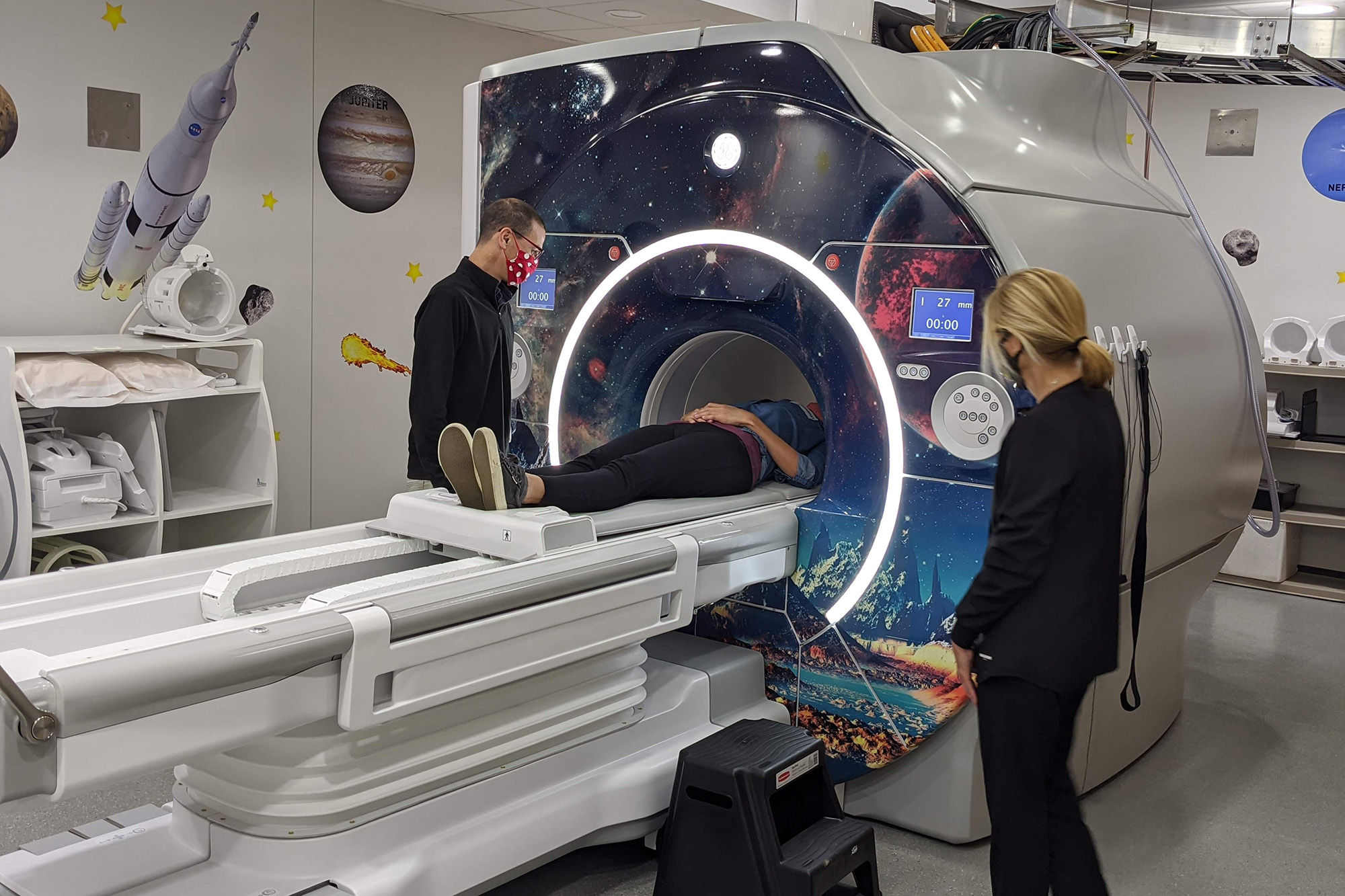

As part of her research examining the brain development of children battling cancer, Ellen van der Plas, assistant professor in the University of Iowa Department of Psychiatry, worked with an Iowa City company to wrap an MRI machine in vinyl to make it more kid-friendly.

Several decades ago, a leukemia diagnosis was an almost certain death sentence for a child. But thanks to advances in treatment, 90% of children with the most common form of childhood leukemia—acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL—now survive.

Despite being one of modern medicine’s great success stories, the treatments that save these children can also cause health problems months, years, and even decades later, making research into such long-term effects important.

“Think about it: you have cancer at 2, and you’re a survivor at 5. You have 60, 70, 80 years ahead of you,” says Ellen van der Plas, assistant professor in the University of Iowa Department of Psychiatry. “These kids have a whole lifetime ahead of them in which they’re potentially struggling. It’s not just about being alive—it’s also about quality of life.”

With the help of families at University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, van der Plas examines the brain development of children battling leukemia.

“Back in the day, there was literally nothing we could do for these children. Now there is,” van der Plas says. “But it’s a harsh treatment. We’re fighting fire with fire. But by learning more, we hope we can make it less harmful.”

“It’s amazing and heartwarming how receptive parents are of it because they know their child isn’t going directly benefit or get better treatments by participating. But they want to help future kids.”

Chemotherapy and radiation can cause cognitive impairments such as memory and attention problems, lower IQ and test scores, slowed development, poor hand-eye coordination, and behavior problems.

Van der Plas says these impairments are often subtle.

“We’re not talking about going from a highly intelligent kid to one who can’t complete a test,” van der Plas says. “We think they grow into certain deficits over time. They initially may need more time to finish homework, and then college may be more difficult because of the increased responsibilities, and when they start working, it becomes even harder to meet societal pressures.”

While completing her postdoctoral fellowship at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada, van der Plas looked at survivors of childhood cancer to understand what, if any, neurodevelopmental problems they had. When she returned to the University of Iowa, where she earned a PhD, van der Plas wanted to determine what happens to the brains of children during cancer treatment.

“We can see differences in the brains of survivors, so we think it must happen during treatment,” van der Plas says. “Many of these kids get leukemia when they are in preschool, and that’s a time when the brain is exploding. They are learning so much. I want to see what’s going on during treatments that can help explain why their brains look the way they do in survivorship.”

Getting into an MRI machine can be intimidating for anyone, but more so for a child. Getting into a spaceship, however, sounds amazing, especially to a child. In the case of an Iowa research lab, wrapping the machine’s exterior with outer-space visuals and ordering a Lego model of the machine have boosted young participants’ cooperation.

To begin, baseline images are needed of the brains of children as close to diagnosis as possible. One of the first challenges van der Plas faced was getting children into the MRI machine without sedating them. “It can be frightening,” van der Plas says. “This giant machine can be extremely intimidating even for adults, let alone a child. We needed something that wasn’t as intimidating.”

Van der Plas consulted with child life specialists and worked with an Iowa City company to cover the MRI machine—as well as a mock scanner that children can play in—with a vinyl wrap to make it look like a spaceship.

COVID-19 has slowed van der Plas’s research, but she says the wrapped MRI machine has proved to be a success.

“The kids seem to like it—and their parents do too,” van der Plas says. “I’ve even had a parent ask me where we got the wrap because they wanted one for home!”

Along with helping kids feel more comfortable, the MRI wrap has had another unexpected benefit.

“It’s proven beneficial when writing grants,” van der Plas says. “I’ve put it front and center, and people like it. I think it shows we’ve really thought about these things. It’s had a huge impact on this research all around.”

This pilot study will follow children from diagnosis through six months, but van der Plas hopes future grant funding will allow them to continue following patients through further treatment and later on as survivors.

Van der Plas says Iowa families have been very open to the idea of participating in her research: 92% of those she approached joined the study.

“It’s amazing and heartwarming how receptive parents are of it because they know their child isn’t going directly benefit or get better treatments by participating,” van der Plas says. “But they want to help future kids.”